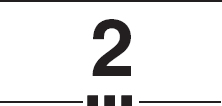

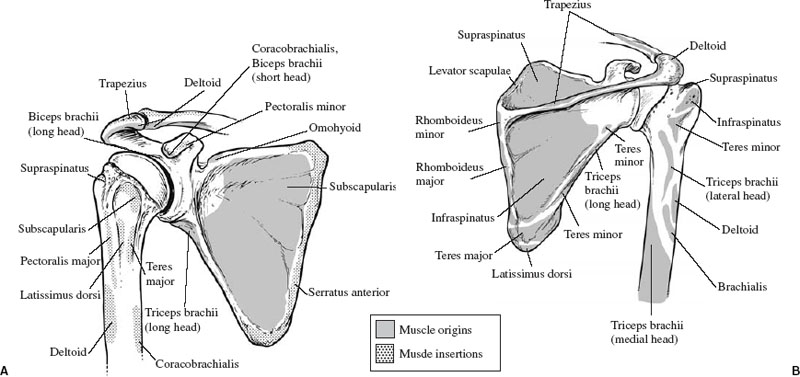

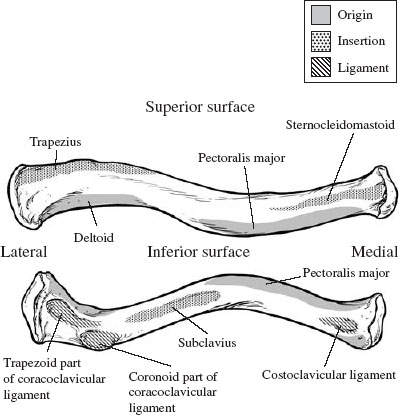

The shoulder is a complex joint composed of four articulations, the sum of whose motions provide for its vast mobility. During the course of evolution, stability has been sacrificed for mobility, especially in higher primates where the upper extremity is no longer a primary weight-bearing appendage. The shoulder is described as having three degrees of freedom: flexion and extension in the paramedian plane, abduction and adduction in the coronal plane, and medial and lateral rotation. The clavicle, scapula, and humerus provide the shoulder’s osseous scaffolding. They share three diarthrodial articulations: the sternoclavicular joint, the acromioclavicular joint, and the glenohumeral joint. The scapulothoracic joint is the fourth articulation of the shoulder; it is formed by the scapula as it rides over the posterior superior thorax on a bed of muscle and bursae. The three bones are manipulated and stabilized to the axial skeleton by 19 muscles. The muscles are divided into an intrinsic group that moves the humerus with respect to the scapula, and an extrinsic group that moves the pectoral girdle and humerus with respect to the axial skeleton. A large flat bone, the scapula rests on the posterior superior thorax and acts primarily as a site of muscle attachment (Fig. 2-1). Almost the entire surface of the scapula is covered by muscle. Thus protected, the body of the scapula is rarely fractured and only by severe direct trauma. Most scapular fractures occur to the vulnerable processes of the scapula: the acromion, coracoid, and glenoid. The scapula articulates with the clavicle, the humerus, and the thorax. The costal surface of the scapula is covered by the subscapularis muscle, which lies in the concave subscapular fossa. Posteriorly, the surface of the scapula is divided by the scapular spine into the supraspinatus and infraspinatus fossae, which contain the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles, respectively. The superior border of the scapula is the site of attachment for the omohyoid muscle. This muscle is just medial to the scapular notch and the superior transverse scapular ligament. The medial border of the scapula serves as the attachment site for the levator scapulae. This medial border is perpendicular to the scapular spine and parallel to the spinal column. The minor and major rhomboids are attached to the medial border. The lateral border of the scapula extends from the inferior angle to the glenoid. From inferior to superior the following muscles attach to the lateral border of the scapula: the latissimus dorsi, teres major, teres minor, and long head of the triceps. FIGURE 2-1 Interior (A) and posterior (B) views of the scapula, demonstrating that it is the origin or insertion site for almost all of the shoulder girdle muscles. Readily palpable on the posterior surface of the scapula is the scapular spine, which arcs anterolaterally, becoming the acromion process. The acromion articulates with the clavicle and serves as the only ligamentous attachment of the scapula with the axial skeleton. The scapular spine serves as the site of attachment for the trapezius and deltoid. Additionally, the scapular spine suspends the acromion laterally and anteriorly, improving the leverage of the deltoid. Overhanging the head of the humerus, the acromion is often implicated in impingement syndromes of the shoulder. In the anterior plane, there is 9 to 10 mm (6.6 to 13.8 mm in men and 7.1 to 11.9 mm in women) of space between the humeral head and the acromion.1 This space is referred to as the supraspinatus outlet. Acromial epiphyseal nonunion, called os acromiale, has been found in 1.4 to 8.2%2 of cadaveric specimens. This can be mistaken for acromial fracture in trauma patients but has not been implicated as a cause of impingement.3 Anterolaterally on the scapula, the coracoid process is an anterior projecting process of bone just medial to the glenoid and inferior to the suprascapular notch. Two ligaments, the coracoclavicular (divided into two bundles, the conoid and trapezoid) and the coracohumeral attach to the coracoid. The coracoid is the origin of the coracobrachialis and short head of the biceps. Inserting into the coracoid at its inferomedial border is the pectoralis minor. At the medial base of the coracoid lies the suprascapular notch, which contains the suprascapular nerve. The glenoid is the disk-shaped lateral process of the scapula inferior to the acromion and lateral to the coracoid. The long head of the biceps arises from the supraglenoid tubercle, a small bony prominence on the anterosuperior aspect of the glenoid. Covered by fibrocartilage, the glenoid articulates with the head of the humerus. Circumferential thickening of the articular cartilage around the outside rim of the glenoid forms the labrum. The labrum is composed of fibrocartilage, which is distinctly different from the hyaline cartilage that covers the articular surface of the glenoid. The articular surface of the glenoid is 6° retroverted with respect to the blade of the scapula. The superior, medial, and inferior glenohumeral ligaments provide the primary ligamentous attachments of the humerus to the scapula, whereas the coracohumeral ligament is a secondary attachment. The superior glenoid tubercle is the origin for the long head of the biceps, and the inferior glenoid tubercle is the origin for the long head of the triceps. Anchoring the scapula to the axial skeleton, the clavicle is an essentially straight bone in the anterior posterior plane but S-shaped in the transverse plane; it is convex anteriorly at its medial third and concave anteriorly at its lateral third (Fig. 2-2). The clavicle’s medial anterior curve accommodates the trunks of the brachial plexus and the subclavian artery. The clavicle acts as a strut to the shoulder, optimizing the glenohumeral range of motion by keeping it lateral to the axial skeleton. The clavicle serves primarily as a site for muscle attachment, but also transfers the force generated by the trapezius to the scapula, resulting in scapular elevation. Scapular elevation maintains glenohumeral joint separation from the axial skeleton and maximizes glenohumeral range of motion. The clavicle is the first bone to ossify during the fifth week of gestation by intramembranous ossification. The epiphyses (growth plates) of the clavicle are late to form and fuse; the proximal epiphysis of the clavicle appears at 18 to 20 years and fuses at about 25 years. The presence of this epiphysis makes differentiating physeal fractures from dislocations of the sternoclavicular joint difficult in the 18- to 25-year-old patient. A small epiphysis appears at the distal end of the clavicle at about 20 years and soon fuses with the shaft of the clavicle.4 The clavicle has two diarthrodial articulations: one with the sternum and one with the scapula. The sternoclavicular joint is the only joint in the entire shoulder construct that articulates with the axial skeleton. The clavicle is the insertion point for the subclavius, sternocleidomastoid, and the trapezius, whereas the pectoralis major and deltoid originate from the clavicle (Fig. 2-2). The costoclavicular ligament anchors the medial third of the clavicle to the first rib, whereas the trapezoid and conoid ligaments anchor the lateral third of the clavicle, leaving the middle third unsupported and prone to fracture. The proximal spherical head of the humerus articulates with the scapula via the glenoid (Fig. 2-3). On average, the radius of curvature of the head is 2.25 cm. The humeral head is generally described as retroverted 25° to 35° with respect to a line drawn through the medial and lateral epicondyles of the humerus. Edelson2 has demonstrated humeral head retroversion to vary from − 8° to 74°. The articular surface is covered with fibrocartilage, which terminates distally at the anatomic neck of the humerus. The borders of the anatomic neck are the greater tuberosity, the lesser tuberosity, the intertubercular groove, and the medial surface of the humerus. This anatomic neck is easily visualized during arthroscopy as a ring of bone devoid of hyaline cartilage that varies from 1 cm wide medially to nonexistent superiorly, proximal to the insertions of the hyaline humeral ligaments and rotator cuff muscles. Distal to the tuberosities, the humerus narrows into an area called the surgical neck.

Anatomy of the Shoulder

Osteology

Osteology

Clavicle

Clavicle

Humerus

Humerus

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree