Hip Joint Infection

James Keeney

Key Points

• Early diagnosis and treatment are important toward optimizing outcomes.

• Clinical history, physical examination, and joint aspiration identify most cases.

Introduction

Septic arthritis is an uncommon, clinically significant condition that can rapidly produce hip joint destruction and physical impairment. If unrecognized or untreated, a septic joint can result in significant localized consequences, including chondrolysis, osteomyelitis, osteonecrosis, and leg length discrepancy1 (Fig. 38-1). Severe systemic complications, including sepsis and death, may occur and have been noted with increased frequency in association with advanced age.2 Early diagnosis and initiation of surgical intervention remain essential components of successful treatment. Although septic arthritis occurs most commonly in children or in adults with prosthetic joint replacements, it remains a significant diagnostic consideration in evaluating other adult patients presenting with hip pain.

Figure 38-1 Loss of right hip cartilage and bone after septic hip.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Epidemiology

The most common pathway for entry of infection into the nonreplaced adult hip joint is a hematogenous source.3 Bacteria from the urinary tract, lungs, skin, or other distant sites have been postulated to enter the hip joint through inflamed or diseased synovial tissue. Although antegrade flow through the arterial system most likely contributes to most cases, the proximity of the hip to Batson’s plexus provides the potential for retrograde venous introduction of bacteria from pelvic floor organs.

Direct introduction of bacteria into the hip joint can also occur through a variety of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures.4 Although inoculation has historically contributed to a small percentage of cases, increasing use of arthrocentesis, arthroscopy, and open surgical approaches in the treatment of nonarthritic and prearthritic hip conditions may result in a higher future incidence of infection associated with these diagnostic and therapeutic interventions.

Regional extension of infection from the lumbar spine, genitourinary structures, and lower gastrointestinal tract can also cause hip joint infection. This may occur by direct communication or by extension of infection along the iliopsoas tendon.5–8

Risk Factors

Conditions that result in increased venous or arterial perfusion, capillary permeability, or synovial tissue inflammation elevate the potential for bacteria to enter into the hip (Box 38-1). Impaired immune system surveillance, caused by host factors, disease, or pharmacologic immunosuppression, further contributes to an individual’s susceptibility for joint sepsis (Box 38-2).

Microbiology

The most common infecting organisms are similar to those encountered with other musculoskeletal infections. Staphylococcus aureus is the most frequently reported organism resulting in hip infection, accounting for between 30% and 60% of cases.2,9-11 Group A streptococcal bacteria are the second most commonly identified, and an increasing number of infections have been reported with a variety of gram-negative and anaerobic organisms (Box 38-3). Recent trends indicate an zincreasing incidence of community-acquired methicillin-resistant strains of S. aureus (MRSA) in Western cultures.5 Among patients with osteonecrosis or sickle cell disease, salmonella has been reported as an organism with a predisposition for the hip at a higher incidence than nonsalmonella infection, and it may be associated with a chronic carrier state within the necrotic bone in susceptible individuals.12

Pathophysiology

Synovial tissue is highly vascularized and permeable. Synovial fluid, synthesized by cells within the synovial membrane, contributes to the nutrition of articular cartilage by active diffusion through the surface cartilage layers during physiologic joint loading.

Pyogenic Infection

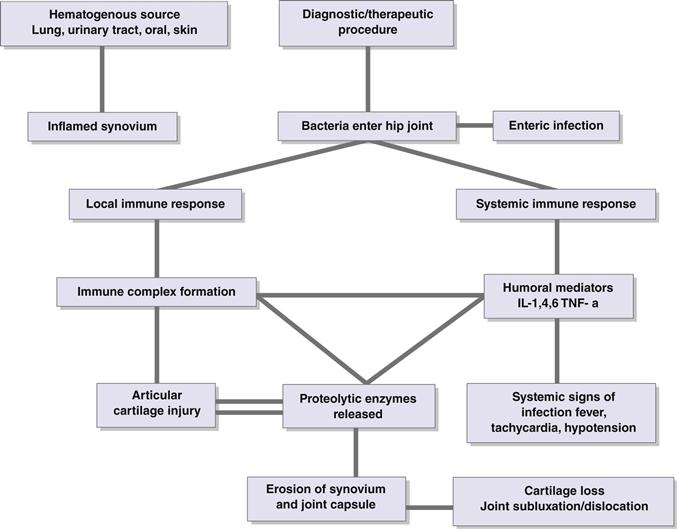

Inflammation of the joint lining from local or systemic disease processes allows bacteria to enter the synovium and to enter the joint along with synovial fluid. After entry into the joint, bacterial growth occurs, inciting a localized inflammatory response and systemic activation of the host immune system. In pyogenic infection, immune complexes are formed, inflammatory mediators are secreted, and proteolytic enzymes are released into the joint, exerting nonselective actions that result in the degradation of articular cartilage. With prolonged exposure, articular cartilage loss can expose subchondral bone interfaces, which can be further weakened by direct effects of enzymatic activity and by inhibitory effects of limited weight bearing on maintenance of bone strength. Intra-articular pressure from an expanding joint effusion can potentially affect the vascular supply to the femoral head and, in rare cases, can produce osteonecrosis. Increased intra-articular pressure, when combined with erosive effects of intrasynovial inflammatory enzymes, can cause capsular disruption and can contribute to the formation of soft tissue abscesses, sinus tract formation, and hip joint subluxation or dislocation (Fig. 38-2).

Figure 38-2 Flow diagram of the pathophysiology of septic joints.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree