Osteolysis Around Well-Fixed Hip Replacement Parts

James I. Huddleston III. and William J. Maloney

Key Points

Introduction

Aseptic loosening from periprosthetic osteolysis is a common cause of late failure after total hip arthroplasty (THA). In the United States in 2006, 24.7% of 51,345 revision hip procedures were performed for mechanical loosening and bearing surface wear.1 In this chapter, we present a strategy for managing periprosthetic osteolysis in the setting of well-fixed implants.

Osteolysis was first described by Harris and associates in 1976.2 At the time, it was believed that this was due to “cement disease.”2–4 Initially seen around cemented femoral components, osteolysis was later observed around cemented acetabular components that failed owing to aseptic loosening. Cementless sockets were then designed to mitigate the failures seen with cemented fixation. Over time, osteolysis was seen around cementless implants as well. It was observed that the processes around cemented and cementless implants were similar histologically.5,6 It is now widely accepted that the process of osteolysis is most commonly driven by the biological response to particulate interface wear debris.5–8

It is important to note that the natural history of osteolysis in cemented and cementless fixation is different. In cemented fixation, osteolysis involving the bone-cement interface typically leads to aseptic loosening.9–12 Surgical management in this situation will consist of revision of the entire implant, and the timing depends on the severity of bone loss and the patient’s symptoms. In cementless fixation, osteolysis more commonly involves periprosthetic bone, and the implants may remain osseointegrated in the setting of even massive bone loss. Revision of the entire implant and bearing exchange with débridement of the osteolytic granuloma and bone grafting are viable options in this setting.

Indications

Patients who develop osteolysis around cemented acetabular components generally present with pain. The radiographic pattern of osteolysis in these patients is usually linear and progresses to involve the entire bone-cement interface. When the entire bone-cement interface is involved, the cup becomes loose. The linear pattern precludes grafting, thus there is not a prophylactic surgical treatment that is practical. Pain is the indication for operative treatment in these patients. The timing of intervention should be commensurate with symptoms; many patients with loose cemented sockets report only mild pain that does not warrant surgical intervention immediately.

Indications for operative treatment of osteolysis around cementless acetabular components are less well defined. Patients with loose cementless sockets have pain, thus the indication for revision is straightforward. Controversy exists regarding the timing of operative intervention in cases where the socket remains well-fixed. In these cases, patients often are pain free, and the issue becomes operating on asymptomatic patients.13 A few small areas of osseointegration can keep cups well-fixed; therefore patients can remain pain free despite expansile lesions.14,15 In general, most experts agree that osteolytic lesions that progress over a 3- to 6-month period are an indication for operative treatment. Severe polyethylene wear may justify a lower threshold for treatment because it is optimal to intervene before the time when the head wears through the liner and engages the shell. Prompt operative treatment is warranted when the head has worn through the liner because this situation will generate metallosis and an intense local inflammatory response from metal and polyethylene debris.

In planning for surgical treatment, it is important to consider that plain radiographs generally underestimate the size of osteolytic lesions.11,14,16-21 In addition to standard anteroposterior pelvis, anteroposterior hip, and cross-table lateral views, Judet views (45-degree obturator and iliac oblique views) often provide information regarding the extent of involvement of the anterior and posterior columns. Helical computed tomography (spiral CT) with metal artifact suppression generally provides the most accurate representation of the size and anatomy of osteolytic lesions.19,21-24

Patients with femoral osteolysis generally remain asymptomatic until an impending fracture or extensive synovitis is present, except when osteolysis is associated with femoral component loosening. As on the acetabular side, the timing for surgical intervention is controversial. Indications for operative treatment in cases of femoral osteolysis include progressive lesions, diaphyseal osteolysis, impending fracture, and pain.

Acetabular Treatment Algorithm

The key issue in treating acetabular osteolysis in the setting of a well-fixed shell is whether to retain or remove the cup. Several early reports recommended removing the entire shell to attain adequate access to the lesion.11,14,15,25 The drawback to this approach is that reconstruction after cup removal is likely to be complex, especially in lesions where the posterior column has been compromised. Key factors in determining whether the shell can be retained include exchangeability of the liner, osseointegration, and type of fixation surface (i.e., two-dimensional [ongrowth] vs. three-dimensional [ingrowth]).

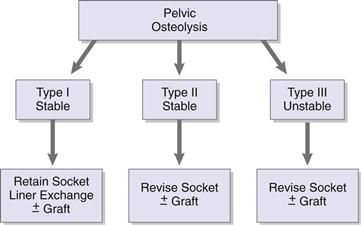

A classification system has been developed to guide surgeons in the treatment of pelvic osteolysis with cementless acetabular components (Fig. 88-1).10,26-30 A type 1 socket is well positioned, has an ingrowth fixation surface, has a modular liner, and has acceptable survivorship. These cases can be addressed with débridement of the lesion and bone grafting at the surgeon’s discretion (Fig. 88-2). Relative contraindications to liner exchange include a damaged shell or locking mechanism and the unavailability of liners with adequate thickness, head size, and/or highly cross-linked polyethylene. An undamaged locking mechanism is only a relative contraindication because it is safe to cement a liner into an appropriate shell.31,32 Unfortunately, no data are available regarding how much shell damage is permissible. Ongrowth fixation surfaces are a relative contraindication to liner exchange because tensile strength between bone and socket is weaker than the same interface with an ingrowth surface. Hydroxyapatite-coated and macrotextured cups are examples of sockets that should not be classified as type I.33–35 Type II sockets are well-fixed but do not meet the criteria for type I sockets. Type II sockets should be removed, and residual bone defects should be managed accordingly. Type III sockets are loose and should be revised.

Figure 88-1 This diagram shows the treatment algorithm for management of osteolysis around osseointegrated acetabular components.

Figure 88-2 These preoperative (A and B) and 2-year postoperative radiographs (C and D) show a type I acetabular case treated with socket retention, granuloma débridement, grafting, and liner exchange.

Femoral Treatment Algorithm

Several key factors must be addressed when treating osteolysis around cementless femoral components. First, stem stability must be determined. Although the surgeon should have an accurate prediction of stability based on interpretation of preoperative radiographs, intraoperative assessment is crucial for corroboration. Second, the extent of osseointegration is an important consideration. The surgeon must be confident that remaining bony apposition to the fixation surface is sufficient to provide long-term implant stability. Third, the location of the lesion is critical. Well-fixed stems with metaphyseal lesions may be retained in many cases. Diaphyseal lesions indicate a connection between the joint space and the distal endosteum.5 These lesions are difficult to access, and stem revision may be required in the setting of progression of the lesion and/or impending fracture. And fourth, the exchangeability of the femoral head should be considered. If the implant is nonmodular, the head must be in good condition and of sufficient size, and the offset and length must be appropriate, to ensure adequate hip stability.

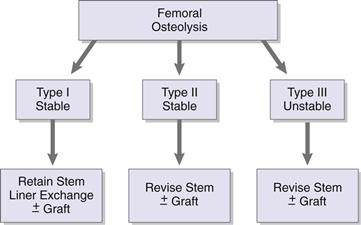

A classification system has been devised to guide surgeons in the treatment of osteolytic lesions around cementless femoral components (Fig. 88-3).28 In type I cases, stems are osseointegrated, lesions are predominantly metaphyseal, and the extent of osseointegration is judged sufficient to ensure long-term stability. In this situation, we recommend stem retention, grafting of contained lesions, and exchange of the femoral head (Fig. 88-4). Relative contraindications to stem retention and head exchange include a fixed femoral head that is damaged or insufficient in size or length to provide hip stability, a limited area of osseointegration, diaphyseal osteolysis, appropriate head not available, and a severely corroded taper. Taper corrosion generates biologically active particulate debris that can lead to third-body wear; it can also weaken the stem and cause implant fracture. In type II cases, the stem is osseointegrated but there is significant diaphyseal osteolysis or insufficient extent of osseointegration, or the femoral head is fixed and damaged. In these cases, we recommend revision of the femoral stem. In type III cases, the stem is loose, thus revision is required.

Figure 88-3 This diagram shows the treatment algorithm for management of osteolysis around osseointegrated femoral components.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree