Hip Arthroscopy—Disorders of the Trochanteric Space—Bursitis and Abductor Tears

Lazaros A. Poultsides

Bryan T. Kelly

Introduction

Lateral hip pain, or greater trochanteric pain syndrome (GTPS), is a common clinical complaint that is often referred to as “greater trochanteric bursitis.” Originally defined as “tenderness to palpation over the greater trochanter with the patient in the side-lying position” (1,2,3), or reproducible pain with resisted abduction (4), GTPS has expanded to include a number of disorders of the lateral peritrochanteric space of the hip, including trochanteric bursitis, external coxa saltans (snapping hip), and tears of the gluteus medius and minimus (5).

GTPS is reported to affect between 10% and 25% of the general population (3,6,7). This clinical entity is more prevalent in women than men, with peak incidence between the fourth and sixth decades of life (8). Patients with this syndrome are often successfully treated with corticosteroid injection (2,4,9). GTPS has also been described in patients treated for osteoarthritis (OA). Howell et al. (10) reported a 20% prevalence of abductor pathology in patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty (THA), whereas Farmer et al. (11) found a 4.6% rate of trochanteric bursitis after THA, of which 80% responded to corticosteroid injection. However, in patients with GTPS who do not respond to conservative treatment or injection, tears of the abductor tendons should be suspected, and MRI may be indicated (12,13). In patients with recalcitrant GTPS who underwent MRI, Bird et al. (8) found that 46% of patients had a tear of the gluteus medius, and another 38% had gluteus medius tendinopathy without tear. These tears are either chronic, nontraumatic tears of the anterior fibers of gluteus medius or tears found coincidentally at the time of open surgical management of femoral neck fractures or elective THA for OA, and can be treated successfully by open repair (14).

Lately, hip arthroscopy has allowed visualization and subsequent treatment of extra-articular pathology found in the peritrochanteric compartment. Arthroscopic bursectomy is an option in recalcitrant cases of trochanteric bursitis (15,16), whereas abductor medius and minimus tendon tears can be successfully repaired arthroscopically (17).

This chapter aims to review the current understanding of the peritrochanteric space including the patient evaluation, relevant anatomy, differential diagnosis, imaging, arthroscopic techniques, and the associated pathology that may be encountered and addressed. In addition, the indications and different open reconstruction techniques will be described to manage massive abductor tears where arthroscopic direct repair cannot be accomplished.

Insertional and Functional Anatomy of the Abductors

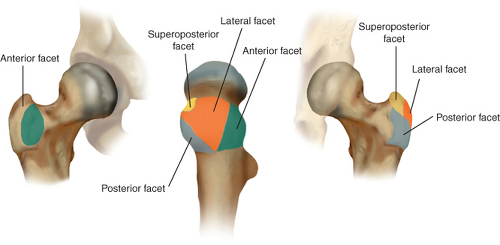

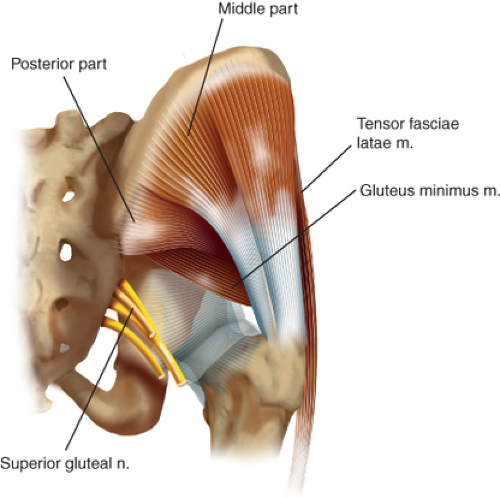

The greater trochanter arises from the junction of the femoral neck and shaft. It is the site of attachment for five muscles, the gluteus medius and gluteus minimus tendons laterally and the piriformis, obturator externus, and obturator internus more medially. It consists of four distinct facets; Dwek et al. (13) classified abductor tears based on their MRI appearance, and divided the greater trochanter into the superoposterior, lateral, anterior, and posterior facets (Fig. 30.1). The posterior facet is the only facet that does not have any distinct tendon attachment but is the primary location of the largest bursae of the peritrochanteric space; therefore, is the likely source of primary pain in patients with true isolated trochanteric bursitis without associated abductor tendon tear (18,19,20). The gluteus medius muscle is a large curved fan-shaped muscle that originates from the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) and the outer edge of the iliac crest back to the posterior superior iliac spine. The muscle has three distinct portions of equal volume—anterior, middle, and posterior—which are innervated by the superior gluteal nerve. The fibers of the anterior and middle parts are vertically oriented and have a vertical pull, and aid in initiating hip abduction (21). The anterior part is also a primary pelvic rotator. The posterior part of the gluteus medius is horizontal, running parallel to the femoral neck. It stabilizes the hip joint in gait from heel strike to full stance (Fig. 30.2). A recent anatomic study showed that the gluteus

medius tendon inserts onto the greater trochanter by two distinct attachment sites—the superoposterior facet and the lateral facet (Fig. 30.3) (22). The posterior gluteus medius fibers insert onto the superoposterior facet of the greater trochanter, which has an approximately circular shape, with a radius of 8.5 mm and a total surface area of 196.5 mm2. Most of the middle portion and the entire anterior portion of the gluteus medius insert into the lateral facet, which has an approximately rectangular shape, with a larger surface area (438 mm2). The lateral facet also contains a bald spot just anterosuperior to the medius tendon insertion.

medius tendon inserts onto the greater trochanter by two distinct attachment sites—the superoposterior facet and the lateral facet (Fig. 30.3) (22). The posterior gluteus medius fibers insert onto the superoposterior facet of the greater trochanter, which has an approximately circular shape, with a radius of 8.5 mm and a total surface area of 196.5 mm2. Most of the middle portion and the entire anterior portion of the gluteus medius insert into the lateral facet, which has an approximately rectangular shape, with a larger surface area (438 mm2). The lateral facet also contains a bald spot just anterosuperior to the medius tendon insertion.

Figure 30.2. Illustration of the lateral hip musculature demonstrating the three parts of the gluteus medius muscle (i.e., anterior, middle, posterior) in relation to the hip joint. |

The gluteus minimus muscle originates from the anterior inferior iliac spine to the posterior inferior iliac spine along the middle gluteal line. The fibers of the gluteus minimus are also horizontally oriented in relation to the femoral neck, and they run parallel to it (Fig. 30.2). The gluteus minimus also stabilizes the hip joint during the mid and late stages of the gait cycle (21). Immediately anterior to the bald spot lies the anterior facet, where the gluteus minimus inserts (22). Specifically, the gluteus minimus tendon inserts into both the hip capsule (i.e., capsular head) and the anterior facet beneath the gluteus medius tendon (i.e., long head). Thus, the bald area lies on the greater trochanter between the capsular head of the gluteus minimus and the lateral facet insertion of the gluteus medius (Fig. 30.2).

When repairing tears of the gluteus medius and minimus, familiarity with the normal anatomy is essential to recreate the true footprint of the tendon. Reports of massive gluteus medius tendon tears have described a “bald trochanter” (23). In evaluating the degree of abductor tears, care must be taken not to overestimate the size of the tendon detachment by mistaking this normal bald spot for the anatomic footprint of the gluteus medius, and consequently placing anchors in and reattaching tissue to the bald spot of the trochanter (5).

Clinical Presentation and Principles of Patient Evaluation and Differential Diagnosis

Typical clinical findings are chronic pain and tenderness over the proximal lateral aspect of the hip, usually directly on or anterior to the greater trochanter. Pain may be worsened by walking, climbing stairs, or lying on the affected hip. The patient may have a slight or moderate limp. Typically, passive hip range of motion is not restricted, but there may be a variable degree of weakness in side-lying abduction.

Evaluation of hip pain requires conducting a comprehensive patient history to differentiate between intra- and extra-articular pathology. Groin pain generally suggests intra-articular pathology, whereas lateral pain that can be reproduced with deep palpation over the trochanter generally represents GTPS. Nevertheless, there is significant overlap with regard to pain location, and patients often present with more than one clinical problem. When this complaint is localized laterally, further differentiation among various peritrochanteric pathologies can then be achieved by focusing on characteristics specific to each pathologic condition. Patients with snapping hip syndrome will complain of an audible or palpable snap as the hip moves from flexion to extension, which can usually be reproduced during physical examination. Trochanteric bursitis and abductor tendon tears are both commonly present with tenderness over the greater trochanter and pain with resisted abduction. However, patients with abductor tears often have a more acute clinical course and will frequently present with weakness of abduction and/or a Trendelenburg gait. In addition, it is important to consider the lumbar spine, sacroiliac joint in the differential diagnosis. The diagnostic differential can be narrowed with descriptive characteristics and physical examination findings specific to each peritrochanteric disorder (Table 30.1). These specific associations will be discussed in the section specific to each disorder of the peritrochanteric space.

Following completion of the patient history, a thorough physical examination of the hip joint and surrounding anatomy, specifically the lateral region of the hip, can then further narrow the differential to allow accurate diagnosis. The patient is requested to walk, and should be observed for a limp, coxalgic or antalgic gait, or frank Trendelenburg gait. The patient is then asked to lie supine on the table, and the hip is taken through a full range of motion, taking note of positions that provoke pain. The most characteristic position of pain with passive range of motion is flexion to 45 degrees, abduction, and external rotation. This position brings the posterior facet of the greater trochanter in close proximity to the ischium and posterior wall of the acetabulum, resulting in crushing of the inflamed soft tissue structures and bursae overlying the posterior facet. To conduct an effective physical examination, a complete knowledge of the origins mentioned above and insertions of the hip musculature is required. Palpation of these regions with insertional

pain may allow differentiation between intra- and extra-articular pathology as intra-articular pathology referred to the peritrochanteric region may occur during active or passive hip motion, but should not be associated with regions that are tender to direct palpation.

pain may allow differentiation between intra- and extra-articular pathology as intra-articular pathology referred to the peritrochanteric region may occur during active or passive hip motion, but should not be associated with regions that are tender to direct palpation.

Table 30.1 Differential Diagnosis Among Various Peritrochanteric Pathologies | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Palpation of the lateral hip should begin with the origin of the gluteus maximus at the inferoposterior aspect of the ileum and sacrum. Both insertions can then be examined in the lateral base of the linea aspera on the proximal femur and the tensor fasciae latae. The gluteus medius should be palpated from its origin on the anterior and middle aspect of the ileum to its two insertions on the lateral and superoposterior facet of the greater trochanter. The gluteus minimus can be examined from its origin deep to the gluteus medius to its insertion at the greater trochanter anterior facet. The greater trochanteric bursa should also be evaluated overlying the greater trochanter at the mid-posterior proximal aspect of the femur. Patients with trochanteric bursitis demonstrate point tenderness over the greater trochanter occasionally associated with warmth and/or swelling.

Physical examination of muscle strength should be conducted in the side-lying position with the hip in flexion to assess the tensor fasciae latae, in neutral to evaluate the gluteus medius, and in extension to evaluate the gluteus maximus. This examination should be performed with the knee both flexed and extended to allow tension and relaxation of the iliotibial band (ITB), respectively. Weakness may be seen with all entities because of pain, but significant weakness may be suggestive of a gluteus medius and/or minimus tendon tear. Also, the 30-second single-leg stance and resisted external derotation tests have been shown to have very good sensitivity and specificity for identifying tendinous lesions in patients with peritrochanteric pain (24).

Ober test may be used to evaluate for contractures of the abductor muscles; it should be conducted with the hip in flexion, neutral, and extension. Classically, Ober test is performed in hip extension to assess tension across the ITB. The knee should then be flexed to relax the ITB and allow effective evaluation of possible gluteus medius or maximus contracture. In this position, the knee should be able to internally rotate such that it can touch the table in the absence of pathologic tension (Fig. 30.4).

Diagnostic Imaging

All patients presenting with hip pain are evaluated with an anteroposterior (AP) radiograph of the pelvis as well as a Dunn lateral radiograph (90 degrees of hip flexion with 20 degrees of abduction and the beam centered on and perpendicular to the hip) providing an orthogonal view of the femoral head and neck to the view provided by the AP pelvis. Both views are useful to assess osteophytes or avulsions of the greater trochanter, enthesopathic calcifications of the abductor tendons (Fig. 30.5), CAM and pincer lesions, loss of joint space, cross-over sign, acetabular dysplasia, and sacroiliac joint pathology. It is recommended that AP pelvis radiographs are performed in neutral rotation and in a standardized position of pelvic inclination, which is indicated by the distance between the symphysis and the sacrococcygeal joint (approximately 32 mm in men and 47 mm in women) (25). Standing AP pelvis radiograph may better demonstrate the functional position of the pelvis.

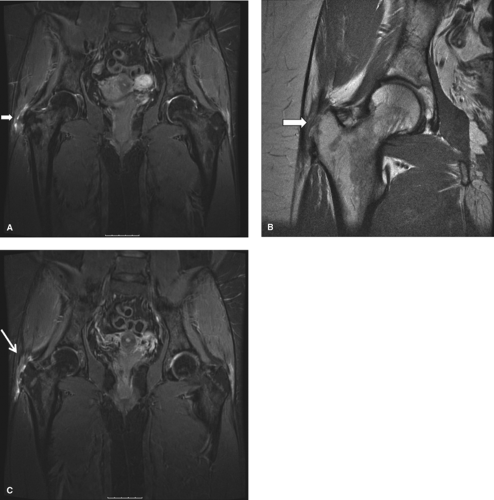

If abductor or other soft tissue pathology is suspected, especially in the setting of refractory trochanteric bursitis with lateral hip pain and an ambulatory limp likely related to hip abductor weakness (23,26), high-quality magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can prove invaluable. MRI provides the most information regarding the soft tissues surrounding the hip (Fig. 30.6A–C) (27). Both noncontrast MRI and gadolinium-contrast MRA can be utilized to evaluate the hip joint (28), which includes a screening examination of the

whole pelvis, acquired with use of coronal inversion recovery and axial proton density sequences. Detailed hip imaging is obtained with use of a surface coil over the hip joint, with high-resolution cartilage-sensitive images acquired in three planes (sagittal, coronal, and oblique axial) with use of a fast-spin-echo pulse sequence and an intermediate echo time (29). Suspected gluteus medius tendon tears in patients with trochanteric bursitis may be confirmed with MRI (26). MRI has showed high accuracy for the diagnosis of gluteus medius and gluteus minimus tendon tears; the identification of an area of T2-hyperintensity superior to the greater trochanter had the highest sensitivity and specificity for tears at 73% and 95%, respectively (Figs. 30.6A–C) (12).

whole pelvis, acquired with use of coronal inversion recovery and axial proton density sequences. Detailed hip imaging is obtained with use of a surface coil over the hip joint, with high-resolution cartilage-sensitive images acquired in three planes (sagittal, coronal, and oblique axial) with use of a fast-spin-echo pulse sequence and an intermediate echo time (29). Suspected gluteus medius tendon tears in patients with trochanteric bursitis may be confirmed with MRI (26). MRI has showed high accuracy for the diagnosis of gluteus medius and gluteus minimus tendon tears; the identification of an area of T2-hyperintensity superior to the greater trochanter had the highest sensitivity and specificity for tears at 73% and 95%, respectively (Figs. 30.6A–C) (12).

Ultrasound can be used to guide diagnostic or therapeutic injections, as well as evaluate the gluteus medius and minimus tendons (30). Sonography can identify gluteus medius and minimus tendinopathy and provides information about the severity of the disease (31). Dynamic ultrasound has also been used to evaluate external coxa saltans, especially when surgical treatment is being considered (30,32,33). It provides real-time images of sudden abnormal displacement of the ITB or gluteus maximus muscle overlying the greater trochanter, which can be correlated with a painful snap during hip motion (30,32,33).

Peritrochanteric Compartment Pathology and Related Outcomes of Treatment

Trochanteric Bursitis

Trochanteric bursitis is characterized by chronic, intermittent aching pain over the lateral aspect of the hip, often with

radiation down the lateral aspect of the thigh or into the buttock. It has been described as an overuse injury, secondary to repetitive friction between the greater trochanter and the ITB with hip flexion and extension, occurring most commonly in older females. It has also been associated with long-distance running younger active patients, low back pain, coxa saltans, ITB syndrome, hip arthroplasty and osteotomy, or other conditions that may alter normal gait patterns (34,35,36,37,38). Schapira et al. (2) documented on this broad differential diagnosis in a 2-year follow-up observational study of 72 patients with symptomatic trochanteric bursitis; 91.6% of these patients had other associated pathology affecting adjacent areas, such as OA of the ipsilateral hip or lumbar spine (5). In addition, patients frequently report symptoms sitting with the affected leg crossed, prolonged standing or walking, and difficulty lying on their affected side secondary to symptoms from direct compression of the inflamed bursa. Moreover, tenderness can be elicited with direct palpation of this region during the physical examination with occasional warmth and/or swelling. Further examination may reveal a positive Patrick-FABERE (flexion, abduction, external rotation, and extension) test and pain with abduction against resistance. The Ober test (previously described) may be used to assess the tension of the ITB, with a positive result when high tension exists.

radiation down the lateral aspect of the thigh or into the buttock. It has been described as an overuse injury, secondary to repetitive friction between the greater trochanter and the ITB with hip flexion and extension, occurring most commonly in older females. It has also been associated with long-distance running younger active patients, low back pain, coxa saltans, ITB syndrome, hip arthroplasty and osteotomy, or other conditions that may alter normal gait patterns (34,35,36,37,38). Schapira et al. (2) documented on this broad differential diagnosis in a 2-year follow-up observational study of 72 patients with symptomatic trochanteric bursitis; 91.6% of these patients had other associated pathology affecting adjacent areas, such as OA of the ipsilateral hip or lumbar spine (5). In addition, patients frequently report symptoms sitting with the affected leg crossed, prolonged standing or walking, and difficulty lying on their affected side secondary to symptoms from direct compression of the inflamed bursa. Moreover, tenderness can be elicited with direct palpation of this region during the physical examination with occasional warmth and/or swelling. Further examination may reveal a positive Patrick-FABERE (flexion, abduction, external rotation, and extension) test and pain with abduction against resistance. The Ober test (previously described) may be used to assess the tension of the ITB, with a positive result when high tension exists.

Despite the fact that calcifications may occasionally be evident within the bursal space around the greater trochanter, plain x-rays are often negative (39). Karpinski et al. reviewed 15 cases of trochanteric bursitis diagnosed based on clinical presentation and point tenderness at the greater trochanter; authors reported that 12 patients had completely normal hip radiographs whereas three had evidence of minimal soft tissue calcification present (4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree