Hip Arthroscopy Anatomy and Access Peritrochanteric Compartment

Andrew E. Federer

Richard C. Mather III

Charles A. Bush-Joseph

Shane J. Nho

Introduction

The peritrochanteric space (PTS) is defined as the area between the iliotibial band (ITB) and the portion of the proximal femur known as the greater trochanter (1). Studies have estimated the prevalence of lateral greater trochanteric pain, also known as greater trochanteric pain syndrome (GTPS), to be 10% to 25% of the population in industrialized societies (2,3). Others have reported that 1.8 patients per 1,000 have GTPS (4). The most affected demographic is women between 40 and 60 years old, which is thought to be because of their wider pelvic morphology (5). The disorders of the PTS have become more widely recognized as a clinical entity that can be treated safely and effectively with either an open or endoscopic approach.

The greater trochanter arises at the junction of the femoral shaft and neck, protruding laterally, and is the site of attachment for five muscles: the gluteus medius and gluteus minimus laterally; and the piriformis, obturator internis, and obturator externus more medially (6). However, only the gluteus medius and minimus attach at what is referred to as the peritrochanteric compartment. These muscles, their associated bursae, the ITB, and the potential space comprise the peritrochanteric compartment and are responsible for the disorders included in GTPS.

The purpose of the present chapter is to characterize the anatomy and pathology of the peritrochanteric compartment with detailed description of the diagnosis and surgical treatment of its disorders.

Anatomy

Gluteus Maximus and Tensor Fascia Lata

The tensor fascia lata (TFL) is a triangle-shaped muscle that arises from a broad tendon along the external lip of the iliac spine between the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) and iliac tubercle (7). Anteriorly it borders the sartorius muscle whereas posteriorly it is contiguous with the gluteus maximus. The thickening of the TFL becomes the ITB approximately at the greater trochanter. The TFL is likened to the deltoid of the shoulder, being the primary abductor of the hip, with support from the gluteus medius and minimus.

The gluteus maximus is the largest and most superficial of the gluteal muscles. It has origin at the posterior gluteal line on the inner upper ilium as well as the posterior lower sacrum and coccyx. The fibers obliquely and laterally descend to insert onto the ITB, just below the greater trochanter. Deeper fibers insert onto the gluteal tuberosity, between the vastus lateralis and the adductor magnus.

Gluteus Medius

The origin of the gluteus medius borders the ASIS, the outer edge of the iliac crest, and the outer edge of the posterior superior iliac crest, allowing the muscle to encompass most of the external surface of the ilium (8). The actual point of contact for the origin is approximately 1 cm broad along the iliac crest (9). The gluteus medius has three equal-sized divisions—the anterior, middle, and posterior—and each is innervated by an independent branch of the superior gluteal nerve through the deep surface of each muscle portion.

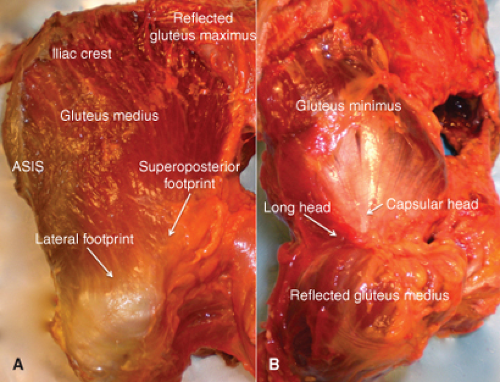

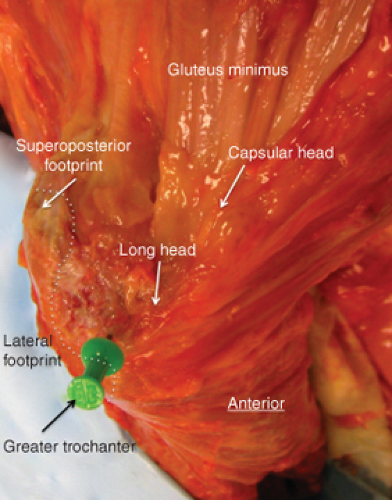

The gluteus medius has two distinct, consistent insertion points on the lateral and superoposterior facets of the greater trochanter (10) (Fig. 27.1). The average longitudinal dimension of the lateral facet is 34.8 mm with a minimal width of 11.2 mm and it has a 36.8-degree angle relative to the long axis of the femur. Inserting into the “upside-down triangle”-shaped lateral facet are the anterior portion and most of the central portion of the gluteus medius. Together, the tendon formed is large, broad, rectangular, mostly muscular in nature and from the undersurface of the muscle belly (10,11). These anterior and middle fibers give vertical pull to initiate hip abduction (9). The rectangular lateral footprint on the posterior greater trochanter has a larger surface area than the superoposterior facet, at 438 mm2 (8).

Inserting into the superoposterior facet of the greater trochanter is the posterior portion and some of the central portion of the gluteus medius. The superoposterior facet is in line with the femoral neck and the inserting tendon is stout and circular (10,11). The tendon fibers of the posterior

gluteus medius run parallel to the femoral neck and help the gluteus minimus stabilize the head of femur in acetabulum during gait (9). The circular superoposterior footprint on the posterior greater trochanter has a radius of 8.5 mm with a total surface area of 196.5 mm2 (8).

gluteus medius run parallel to the femoral neck and help the gluteus minimus stabilize the head of femur in acetabulum during gait (9). The circular superoposterior footprint on the posterior greater trochanter has a radius of 8.5 mm with a total surface area of 196.5 mm2 (8).

Gluteus Minimus

The origin of the gluteus minimus is on the external iliac fossa between the anterior and inferior gluteal lines, running between the anteroinferior and posteroinferior iliac spine (12). More specifically, it has anterior origin on the ridge between the anterosuperior and anteroinferior iliac spines, whereas posteriorly it wraps around the greater sciatic notch into the pelvis, where it protects the superior gluteal nerve and artery (9,12). Distally, the fascia of the gluteus minimus capsular head thickens and inserts onto the superior aspect of the hip capsule, as the rest of the tendon continues toward the greater trochanter. Several studies have noted the presence of an accessory muscle to the gluteus minimus, termed “gluteus quarteus” or “gluteus scansorius” (12,13,14). It arises from the fascia covering the gluteus minimus at the lateral edge of the iliac crest between the ASIS and the iliac tubercle. Descending from its origin, the gluteus quarteus crosses the gluteus minimus and inserts on the posterior greater trochanter, aiding in internal rotation (12,15).

The distal gluteus minimus tendons have two heads, the capsular and long head, that both insert anterior to the gluteus medius on the inner aspect of the anterior margin of the greater trochanter (Figs. 27.1 and 27.2). The capsular head’s footprint is directly anterior to the greater trochanter whereas the long head’s insertion is both anterior and inferior. The capsular head forms from the gradual thickening of the fascia surrounding the muscle until it becomes the tendon as it inserts into the femoroacetabulum joint capsule, which at this area of contact is considered to be the iliofemoral ligament at the anterior rim of the greater trochanter (12). The irregular capsular footprint measures 10 to 15 mm medial-laterally and 20 to 25 mm caudal-cranially (12).

The tendon continues to the long head footprint, which is directly inferior to the “bald spot” of the greater trochanter. The bald spot is an area whose center lies 11 mm distal to the tip of the greater trochanter and 5 mm anterior of the trochanter midline. It also falls between the capsular head and gluteus medius footprints on its anterior and posterior sides, respectively. It is usually ellipsoid in shape with a diameter of about 21 mm and has no tendinous insertions (16). Robertson et al. (10) reported that although the bald spot lacks tendinous insertions, it is covered by the subgluteus medius bursa. The area anterior and medial to the long head insertion might be covered with a thin layer of fibrocartilage, which forms the bottom of the gluteus minimus bursa (12). The insertion points of the gluteus minimus have a great deal of variability in their shape, ranging from “irregular L-shape” to a triangular area (12) (Fig. 27.2). Following the muscle from origin to insertion, the most posterior fibers run at 75 degrees to the most anterior fibers because of its fan-like shape. At 90-degree hip flexion all of the gluteus minimus fibers run straight, directly from origin to insertion (12).

Gottschalk et al. (9) believe the major function of the gluteus medius and minimus is to stabilize the femoral head

in the acetabulum during different positions, rotations, and stages of gait. The authors reported that the gluteus medius and its three divisions stabilize the femoral head in the acetabulum during the initial stages of the gait cycle whereas the gluteus minimus takes on this responsibility during the mid to late stages of the gait cycle. Secondarily, they initiate hip abduction, with the TFL completing the motion (12,17,18). These mechanics are very similar to that of the shoulder rotator cuff, where the supraspinatus and infraspinatus initiate and assist the abduction motion that the deltoid completes.

in the acetabulum during different positions, rotations, and stages of gait. The authors reported that the gluteus medius and its three divisions stabilize the femoral head in the acetabulum during the initial stages of the gait cycle whereas the gluteus minimus takes on this responsibility during the mid to late stages of the gait cycle. Secondarily, they initiate hip abduction, with the TFL completing the motion (12,17,18). These mechanics are very similar to that of the shoulder rotator cuff, where the supraspinatus and infraspinatus initiate and assist the abduction motion that the deltoid completes.

Trochanteric Bursae

The bursae of the peritrochanteric compartment fall into one of the three subgroups: subgluteus maximus bursae, subgluteus medius bursae, and gluteus minimus bursa.

There are four separate subgluteus maximus bursae: deep subgluteus maximus, secondary deep subgluteus maximus, superficial subgluteus maximus, and gluteofemoral bursae. Together they are located lateral to the greater trochanter, deep to the gluteus maximus and ITB, and superficial to both the posterior and lateral aspects of the greater trochanter as well as the distal–lateral gluteus medius tendon (19). They do not extend over the anterior border of the lateral facet, which is the insertion point for the anterior and most of the central gluteus medius tendon (11). The deep subgluteus maximus bursa is commonly referred to as the “trochanteric bursa,” and is the most frequently implicated bursa of trochanteric bursitis.

The subgluteus maximus bursa, or the greater trochanteric bursa, resides in an area innervated by branches of the obturator, femoral, and sciatic nerves; therefore, inflammation to this area can result in significant pain (20,21). Furthermore, the various branches of innervation often result in radiating pain that can lead to misdiagnosis.

The second subgroup of bursae is the subgluteus medius bursae. According to Woodley et al. (22), this subgroup has up to three separate bursae with the largest at the anterior surface of the greater trochanter near its apex. These bursae also cover the “bald spot” of the anterior greater trochanter (16).

Iliotibial Band

The ITB is a fibrous band of tissue that originates largely at the iliac tubercle and travels down past two joints to insert at the lateral tibial tubercle. It is also considered to be the thickening of the fascia originating from the TFL and, to a lesser degree, the gluteus maximus (24). The anterior ITB has superficial and deep layers that “envelop” the TFL (24). Though much of this fibrous band of tissue originates at the iliac tubercle, the superficial layer has connections to the iliac crest and the ASIS (24) whereas the rough, deep layer attaches at the upper acetabulum with the iliofemoral ligament. The TFL muscle originates from the anterior underside of the iliac crest and descends to attach to the ITB. The ITB is described by Evans (25) as the “vertical component of the fascia lata of the thigh” and is noted as a ligament of “great strength and some elasticity.” Gottschalk et al. (9) described the TFL as being the primary actor in isolated hip abduction, with its force acting directly upon the ITB. Evans (25) reported that the ITB assists the gluteal abductors to prevent the Trendelenburg gait and sign. Though the ITB does not directly attach to the femur, the lesser portion of the gluteus maximus blends into the ITB whereas the larger portion inserts onto the gluteal tuberosity, providing indirect attachment of the ITB to the femur (24). The ITB is tightest at the hip during full extension of the hip and knee, coupled with full hip adduction (25). It can be further tightened by contraction of the TFL and the gluteus maximus (24). During flexion the thickened portion of the ITB passes anteriorly over the greater trochanter and during extension it passes back over to the posterior greater trochanter. The sliding back and forth of this taut band causes the “snapping phenomenon.” Between the ITB (where a portion of the gluteus maximus inserts into it) and the greater trochanter lies the greater trochanteric bursa (subgluteus maximus bursa), which also lies superficial to the tendinous attachments of the gluteus medius and vastus lateralis muscles (26). The average thickness of the ITB at the ASIS is 59 mm whereas it is 90 mm at the subtrochanteric region, showing increased thickness over the greater trochanter.

Common Pathologies of the Peritrochanteric Compartment

Abductor Muscle Tendinopathy and Tears

Lachiewicz (8) reported three clinical scenarios in which hip abductor muscles are found to be torn: (A) chronic, nontraumatic tears of anterior gluteus medius; (B) tears found coincidentally at the time of elective total hip arthroplasty (THA) or femoral neck fracture surgery; and (C) abductor tendon avulsion following anterolateral or transgluteal THA.

Of the three types of tears, the first is most commonly treated with arthroscopy. Chronic, nontraumatic tears of the anterior gluteus medius variety were described by Kagan (27) as “rotator cuff tears of the hip.” He found them relatively common in patients diagnosed with ostensible recalcitrant trochanteric bursitis. Other authors have reported similar results; both Bard and Kingzett-Taylor et al. (28,29) suggested that abductor tendinopathy, especially gluteus medius tendinopathy, to be the most common cause of GTPS. In a study of 482 consecutive hip arthroscopies by Voos et al. (30), 10 patients required gluteus medius repair and were evaluated prospectively. At 1-ear postoperation, all 10 patients regained 5/5 abduction strength with modified Harris Hip Scores and Hip Outcome Scores averaging 94 and 93, respectively. All 10 had complete resolution of their pain. Seven patients reported their hip was “normal” whereas the remaining three rated their hip as “nearly normal.”

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree