26 GENITOURINARY INJURIES AND RENAL MANAGEMENT

Rapid diagnosis and treatment of genitourinary (GU) trauma can be difficult. The trauma victim’s most immediate requirement is the establishment of a patent airway, sufficient ventilation, and adequate circulation. Assessment of the GU system often begins with the insertion of a urinary catheter to monitor urine output. This chapter addresses the assessment, treatment, and care of the patient with GU trauma; potential complications; and the impact of GU injury on the recovering trauma patient.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Injuries to the GU tract account for 8% to 10% of all abdominal trauma.1 The most commonly injured organs of the GU tract are the kidneys.2 Renal injury occurs more frequently in children than in adults, and the kidney is the third most common organ injured with abdominal trauma in the pediatric population.3 Injury to the urethra is more common in men than in women because of the anatomic differences.4 Trauma to the ureters is rare and most often has an iatrogenic cause, such as obstetric-gynecologic surgery.5

GU trauma is rarely an isolated injury. Approximately 60% to 80% of patients with blunt renal trauma have associated major injuries to other organs.2,6 Injuries that occur most frequently with GU trauma include fracture of the pelvis, lower rib fractures, intra-abdominal organ injuries associated with gunshot wounds to the abdomen, and fracture of the transverse processes of the lumbar spine. Pelvic fractures have been associated with a 5% to 10% incidence of bladder injury and a 1% to 11% incidence of posterior urethra injury.7–9 In contrast, at least 94% to 97% of patients with bladder injuries have concomitant injuries such as pelvic or long-bone fractures.9 Injury to the right kidney is most often seen with injury to the liver, whereas injury to the left kidney and the spleen tend to occur together.

MECHANISM OF INJURY

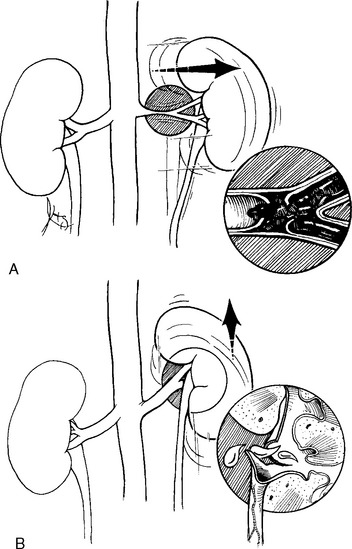

Blunt trauma causes approximately 80% to 95% of all GU trauma.10 Blunt forces can be either direct impact or rapid deceleration. Rapid deceleration injury is produced when a body in motion is halted abruptly. This situation can occur during a fall from a height or in a motor vehicle collision (MVC) when the occupant makes contact with the dashboard, lap belt, or steering wheel of the vehicle. The kidney is set in motion on its pedicle while the aorta remains more stationary. The rotation around the pedicle may tear the intima of the renal artery, resulting in renal artery thrombosis, or may injure the renal vein.11 Other consequences of this type of blunt injury include disruption of the ureteropelvic junction (UPJ) and contusion of the renal parenchyma (Figure 26-1). UPJ injuries occur mostly in children.3 In trauma the most common blunt cause of ureter injury occurs when the kidney is compressed against the lower rib cage and upper lumbar transverse processes, thereby stretching the ureter in lateral flexion.7

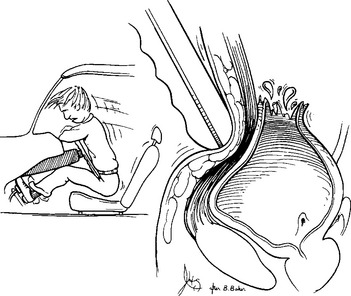

MVCs account for a majority of GU injuries, especially in children.3 During an MVC an unbelted victim slides forward, the femur is compacted into the pelvis, and the abdomen strikes the steering wheel (Figure 26-2). The stress on the kidney is created by a combination of forces applied to the fluid-filled inner compartment. Hydrostatic, or pushing, pressure results in injury. This compression causes an increased intrapelvic pressure that can tear and shear renal structures. Certain preexisting conditions, such as hydronephrotic kidneys and renal cysts, already cause an increased intrapelvic pressure and therefore patients with these disorders have an increased susceptibility to injury, particularly at the periphery.

(From Guerriero WG, Devine CJ: Urologic injuries, p 113, Norwalk, CT, 1984, AppletonCentury-Crofts.)

The use of three-point restraint seat belts decreases the incidence of organ injury by holding the occupant firmly against the seat and allowing the vehicle to absorb the impact of the collision.12 A lap belt alone (without the shoulder strap) or an impact against the steering wheel can result in abdominal injury caused by the sudden increase in intra-abdominal/intravesicular pressure that occurs as the organs are compressed between the abdominal wall and the spine.12 Although airbags have helped reduce overall mortality rates, they only provide supplemental protection for occupants wearing a seat belt and their use alone (in the absence of three-point lap belts) does not decrease the risk of injury.12

Although the incidence of trauma to the ureters is rising with the increase in gunshot wounds (GSWs), the most common cause of ureteral trauma remains iatrogenic injury during surgery.13 Iatrogenic injuries to the small ureters are most likely to occur during difficult pelvic procedures in which normal anatomic landmarks are obscured by obstruction, neoplasm, inflammation, congenital anomalies, traumatic displacement, or the effects of radiation. A high index of suspicion must be established to detect and appropriately treat iatrogenic GU trauma.

In noniatrogenic ureter trauma, penetrating injury is the most common cause of ureter injury.5,7,9 Causes of penetrating trauma include GSWs, stabbing, and impalement. Approximately 4% of injuries caused by abdominal GSWs involve the ureter.13

In addition to the increasing rate of penetrating injuries, another mechanism that causes GU injuries is straddle injuries. Straddle injuries may occur from motorcycle crashes and straddle-type falls.14 Injuries range from external perineal injury, urethral injury, and rectal and vaginal tears.15 The most common form of injury with this mechanism is trauma to the external genitalia. In one study of 43,056 adult victims, there were 78 cases involving these straddle-type injuries caused by motorcycle crashes. In 64% of these cases the injury involved the external genital organs and specifically the testicles in two thirds of cases.16

RESUSCITATION PHASE

Assessment of GU trauma is based on multiple strategies. No one strategy is sufficient to diagnose GU trauma specifically. An accurate diagnosis occurs through the interpretation of diagnostic clues obtained from the history, physical examination, and radiologic and laboratory testing. However, a high index of suspicion, based on knowledge of the mechanism of injury, is key in the detection of GU trauma. GU trauma should be suspected in the following types of injuries1,2,3,5,10,14:

• Abdominal, flank, lower chest, back, or pelvis injury

• Powered personal watercraft events

• Motorcycle and bicycle crashes

HEALTH HISTORY

A health history always begins with the circumstances causing the person to seek treatment within the health care system. The initial step of the assessment is to obtain an accurate history of the events leading to injury. Details about the mechanism of injury provide valuable clues to the occurrence, nature, and extent of the GU trauma.2

In addition to the circumstances of injury, essential medical history information includes allergies, medications, previous diseases or surgical procedures, last meal eaten and when, and the events before the trauma. A quick way to remember the components of the essential health history is the AMPLE acronym, which stands for allergies, medications, past history of medical or surgical illnesses, last meal, and events preceding the injury.17 Previous injuries, known anatomic abnormalities, and preexisting GU conditions should be determined.

Part of the subjective data obtained should include determining whether the patient feels an inability to void. Inability to void may indicate upper urinary tract injury, obstruction caused by blood clots, or bladder or urethra rupture.1,5

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Inspection

The first phase of the physical examination is inspection. Abdominal and flank symmetry should be assessed; evidence of torso or pelvic trauma may extend to evidence of GU trauma.1 The presence of a complex or open pelvic fracture, the number and location of wounds caused by penetrating trauma, and the position of impaled objects must be noted. Impaled objects should not be removed until the patient is in the operating room. Grey Turner’s sign (ecchymosis over the posterior aspect of the eleventh or twelfth rib or the flank) may indicate renal trauma or retroperitoneal bleeding.18 Frequently, renal injury is the result of a direct blow to the flank.1 Absence of ecchymosis does not rule out renal trauma because a significant proportion of patients with renal trauma do not have Grey Turner’s sign. Fractures of the eleventh or twelfth rib or a lumbar transverse process may contribute to renal or ureteral injury.

Assessment of the perineum is integral to patient management. The urinary meatus must be inspected for signs of bleeding, a strong indicator of urethral injury, although it can be absent.1,14 The assessment of the urinary meatus is essential before a urinary catheter is placed.19 The perineal area should be assessed for evidence of trauma, including lacerations, hematomas, swelling, and ecchymosis.1,14

The scrotum may be edematous or contused because of extravasation of urine or blood in patients with urethral injury, pelvic fracture, or retroperitoneal hematoma.5,6 Diffuse perineal bruising is a later sign of fracture of the symphysis pubis or pelvic rami. Perineal swelling, vaginal bleeding, vulvar hematoma, and rectal tenderness are all indications of potential GU injury in female patients from straddle injury, fall, MVC, or assault. For women with an altered level of consciousness, a brief pelvic examination should be performed to ascertain any injury and to determine the presence of a tampon, diaphragm, or intrauterine device.

In patients who have sustained blunt trauma and have vaginal bleeding or pelvic fractures, the possibility of vaginal laceration should be considered.6 Evaluation for such injury is done under direct vision with a speculum or retractors. In the patient with a severe pelvic fracture, the examination usually must be done in an operating suite with the patient under anesthesia. Separation of the legs for examination of a patient with a severe pelvic fracture can result in hemorrhage from pelvic bleeding. This should be avoided at all costs. After the pelvis is stabilized, vaginal examination can occur in the operating suite.

Percussion

Percussion of the abdomen and flank allows assessment of abnormal areas of fluid or air collection.20 Excessive dullness in the lower abdomen or flank may indicate the extravasation of blood or urine or the presence of a retroperitoneal hematoma. Percussion over the kidneys determines their location in the retroperitoneum.

Palpation

The flank, abdomen, lumbar vertebrae, and lower rib cage are palpated for evidence of pain, mass, or crepitus—all potential indicators of GU trauma.1,8,20 Renal colic or costovertebral angle pain may indicate renal trauma.19 Renal colic may be the result of clots obstructing the renal collecting system.19 Severe costovertebral angle pain may be caused by ischemia from a renal artery thrombosis. Additional signs beyond abdominal tenderness, with or without distention, include a flank mass or a pelvic fracture.10 The pelvic area is palpated for evidence of tenderness or movable bony fragments, which may indicate pelvic fracture.6,19 Palpation of the suprapubic area may reveal a distended bladder. Severe tenderness in the hypogastrium may signify bladder rupture.20

A rectal examination should also be performed before urinary catheterization, especially in men. The presence of a boggy or displaced prostate may suggest urethral injury, although a large pelvic hematoma can make the prostate difficult to palpate.6,20

LABORATORY STUDIES

On admission, blood studies are done to establish baseline profiles. Hematologic studies may indicate hemorrhage, but other sources of blood loss must be ruled out before the assumption is made that the cause lies in the GU tract. From a GU perspective, the primary laboratory study is urinalysis. Gross hematuria correlates with significant lower urologic injury.10 Hematuria is a common sign of renal trauma and is present in 80% to 94% of cases, but it can often be transient or even absent, especially in certain types of penetrating injuries.2 Microscopic hematuria may indicate minor injury to the GU tract and requires continued monitoring.2

Because urine obtained by catheterization usually contains 5 to 10 red blood cells per microscopic field, it is optimal if the patient can be encouraged to void the initial specimen. This allows the differentiation between hematuria caused by catheterization and hematuria caused by GU injury. The absence of hematuria, however, should not lead the trauma team to falsely assume that there is no GU injury because up to 36% of patients with major renal trauma have been found to have a normal urinalysis.1

RADIOLOGIC STUDIES

Radiographic assessment of the patient with GU trauma is the cornerstone of the diagnostic process. The primary study of value is computed tomography (CT), yet other studies can provide valuable information about the organs they assess. Patients who require urologic imaging typically have gross hematuria or microscopic hematuria and hemodynamic instability.10 One recent study indicated a need for radiographic imaging in hemodynamically stable patients with microscopic hematuria.2

Computed Tomography

CT provides the most precise delineation of GU trauma. The test is particularly sensitive in staging renal lacerations (the extent of injury) and in identifying intrarenal and subcapsular hematomas, renal infarct, contrast extravasation, the size and extent of a retroperitoneal hematoma, renal perfusion, and associated injuries to abdominal organs.10 By use of contrast medium, arterial injury and lack of perfusion can also be demonstrated. CT is also used to monitor progress in nonoperative management of renal injury.1 CT has essentially replaced intravenous pyelogram (IVP) as the gold standard for renal evaluation.10 After administration of oral or intravenous (IV) contrast, a spiral CT scan with excretory delayed films is performed to diagnose upper urinary tract injury.2,9

Renal Angiography

Renal angiography is indicated when there is incomplete or absent visualization of one or both kidneys on CT, prolonged bleeding without another source, suspicion of renal pedicle trauma, or questionable renal viability. Angiography provides information concerning the preservation of blood supply to the damaged renal parenchyma. Devitalized areas must be identified because necrosis or abscess formation may follow. In penetrating renal trauma after IVP or CT, renal angiography is the second study of choice because it can stage the level of injury reliably and offers the option of embolization versus surgery for hemorrhage control.10 In patients who have significant abdominal trauma, hemodynamic instability may prevent the use of renal angiography because the reduced blood flow may impede visualization. Instead, assessment of the GU tract may occur during emergency celiotomy.5,6,18

Ultrasonography

Renal ultrasonography is capable of detecting renal abnormalities with the use of high-frequency sound waves. The sound waves produce echoes, which are amplified and converted by a transducer into electric impulses that are seen on an oscilloscope screen as anatomic pictures. A negative ultrasonographic study does not exclude renal injury and is therefore seldom used for early identification of injury. Ultrasonography is most useful for the identification and serial evaluation of perinephric hematomas and urinomas. In the acute resuscitative period, the use of the focused assessment with sonography for trauma to detect abdominal injuries has also been shown to be unreliable in detecting GU injuries.10

Intravenous Pyelogram

The IVP, also known as the excretory urogram, is one of the fundamental diagnostic procedures in the assessment of patients with renal trauma. The IVP evaluates both structural integrity and excretory function of the renal system. It also allows visualization of renal parenchyma, calices, and pelvis; assessment of perfusion to the injured kidney; evaluation of the status of both the injured and noninjured kidney; and appraisal of the continuity of the collecting system.1,19 In trauma patients a one-shot IVP is usually performed to save time; this is used purely to confirm the presence of two functional kidneys or massive disruption of the kidneys before surgery.19 In addition to urologic trauma, abnormalities such as polycystic kidneys, absent kidneys, renal calculi, hydronephrosis, and pyelonephritis may be identified. Currently use of the one-shot IVP is under question because CT is more valuable in GU assessment because it is more sensitive than the IVP. The IVP has been know to have a high false-negative rate for patients with penetrating trauma.10,19 One-shot IVP may be valuable during surgery to evaluate pedicle injury and contralateral kidney excretion.1 The study is not accurate if osmotic diuresis is induced or when hypotension is present, resulting in decreased excretion of urine.

Retrograde Urethrogram

The retrograde urethrogram (RUG) is the diagnostic procedure conducted before catheterization of a patient suspected of having an injury to the urethra.5,19 To perform this test, an 8F urinary catheter is attached to an irrigating syringe filled with contrast material. The catheter is gently inserted into the urinary meatus until the catheter balloon is 2 to 3 cm proximal to the meatus.19 The balloon is inflated 1.5 to 2 ml and then 15 to 20 ml of contrast is gently injected into the urethra.19 It is important to bear in mind that there is always a chance that placing a urinary catheter can convert a parital tear to a complete one. If a urinary catheter is already in place, a pericatheter RUG can still be performed to identify urethral injury.

Extravasation of the contrast material detects urethral injury. Partial urethral injury is identified through extravasation with bladder filling, whereas a complete tear of the urethra involves extravasation with loss of continuity.21 The amount of extravasation seen cannot be used to determine the extent or type of injury because this would be largely dependent on the volume and rate of contrast infused. Rather, the extravasation will determine whether there is loss of continuity.

Cystogram

The cystogram is used to detect intraperitoneal or extraperitoneal bladder rupture.5,6 A urethral catheter is passed (after urethral injury is ruled out) and the bladder is filled with at least 300 to 500 ml of water-soluble contrast medium.5,19 Fluid is instilled by gravity to avoid filling the bladder under pressure, which could cause a small tear or even bladder rupture. Anteroposterior and oblique radiographic films are obtained. The bladder is emptied and an anteroposterior postdrainage radiograph is taken. The cystogram should be performed before the IVP.19 Bladder contusions appear normal on a cystogram.5 A false-negative study occurs if there is incomplete distention of the bladder or if no drainage radiograph is done.2 CT cystograms have been found to be 85% to 100% accurate so they can be used instead of conventional cystograms when CT scanning is already being done to rule out abdominal injury.10

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Although magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides excellent imaging, studies have demonstrated that there is no advantage of using MRI over CT imaging.2 The increased cost, extended time, and potential nonavailability of MRI versus CT makes its use only applicable in the rare cases where the patient has an iodine allergy.10

SPECIFIC ORGAN INJURY

TRAUMA TO THE PERINEUM

Trauma to the genital organs, although often not life threatening, can produce overwhelming loss and crisis for the patient and significant others. Genital trauma may be associated with injury to the perineum, bony pelvis, thighs, bladder, vagina, and rectum. Blunt trauma, burns, and penetrating trauma all may produce genital trauma. Fortunately, trauma to the genitals is not common, and surgical intervention can produce good results in both function and appearance. Hemorrhage of the external genitalia is usually controlled by compression dressings, clamps, or ligation.22 These wounds are further managed by wound irrigation and debridement to preserve tissue viability.19

Male Genitalia

Scrotum.

Management.

Penetrating injury to the scrotum can result in injury to the spermatic cord and testes. The salvage rate for the testes is approximately 35%.19 Early debridement and primary repair are essential. Delayed repair is associated with a 21% increased rate of orchiectomy compared with 6% in those who had primary repair immediately after injury.19 Associated injuries may be present, affecting the thighs, femoral vessels, small bowel, or colon.19

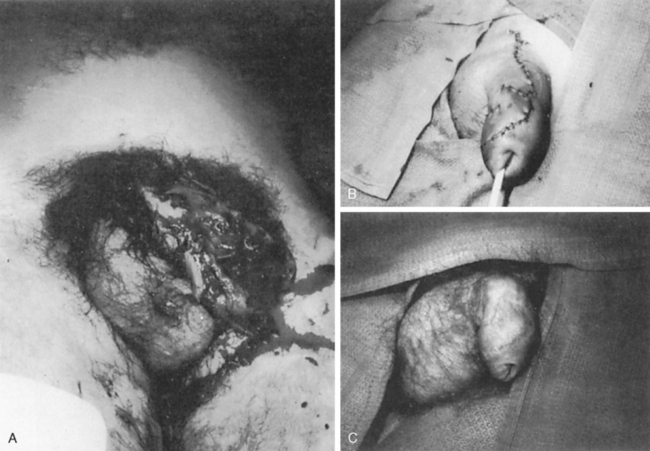

Penis.

Trauma to the penis may be a result of blunt trauma, strangulation injury, mishaps during sexual intercourse, amputation, or penetrating injury (Figure 26-3).19,23,24 Patients with penetrating trauma to the penis have associated injuries of the thigh, scrotum, pelvis, buttock, or abdomen 80% of the time.19 Blunt trauma usually produces a penile fracture with rupture of the tunica albuginea, hemorrhage, and hematoma formation.5,19,23,24 Of these injuries, 10% to 30% result in urethral injury as well.25 The patient presents with pain, swelling, discoloration, and deviation.23 If the injury occurs from striking against a hard object, a direct blow, or abnormal bending, a snap or crackle may have been heard at the time of injury, suggesting fracture.5,19,23–24 Penetrating injuries to the penis involve the urethra in 17% to 22% of cases.25 Indications that the urethra is involved are discussed later in this chapter.

Management.

Injury to the penis can be treated either conservatively or with immediate surgical repair.19,23–25 Conservative treatment includes urethral catheterization or suprapubic cystostomy, application of ice, elevation, administration of anti-inflammatory drugs, compression dressings, analgesics, and medication to temporarily suppress erections.19 Complications of conservative treatment include penile abscess formation, urinary extravasation, pain, inadequate erection, and permanent deformity.23 Patients with penile injury have a 10% to 53% complication rate.23 Surgical intervention is advocated as the treatment of choice to decrease the incidence of complications and to promote rapid recovery.19

Burns involving the genitalia are rare, occuring only 1% of the time, and are usually associated with patients who have extensive burns over their bodies.17 Most genital burns can be treated conservatively with dressing changes, but excision and grafting may be necessary with severe, full-thickness burns, and circumferential penile burns may require early escharotomy to preserve function.17

Female Genitalia

Trauma to the female genitalia is caused by straddle falls, MVCs, and sexual assault.14,26,27 Pelvic fractures, which account for the majority of female external genital trauma, most often injure the vagina and perineum.7–9 Penetrating trauma also may injure the uterus and ovaries, which may require surgical repair, hysterectomy, or oophorectomy.

Perineum.

External perineal injury may present as vulvar hematoma after a straddle event or sexual assault. Assault further involves tears of the introitus.26 The most common injuries in young girls involve the vulva (63%) and vagina (53%).26 Concomitant anorectal lacerations may be noted. Sexual assault may also result in lacerations to the urethra, especially in young girls or women with an imperforate hymen.26 Use of a colposcope, a free-standing microscope used outside the speculum, has significantly increased the documentation of injuries sustained from sexual assault.28 The colposcope allows increased visualization through magnification. Table 26-1 lists the genitalia injuries sustained in order of frequency by age group.28

TABLE 26-1 Female Genitalia Injury After Sexual Assault

| Age Group | Injury in Order of Most to Least Frequent |

|---|---|

| 0-12 years | Hymen, labia minora, posterior fourchette, rectum into hymen, rectum |

| 13-17 years | Hymen, posterior fourchette, labia minora, cervix/vagina into hymen, cervix |

| Adult | Hymen, cervix, posterior fourchette, vagina into labia minora, cervix, periurethral area |

Vagina.

Vaginal tears occur during sexual assault and frequently during straddle-type injuries. A high-speed fall onto water, such as a fall from a Jet Ski, carries sufficient force that the water behaves as a solid object, resulting in vaginal and perineal laceration.29,30 Regardless of mechanism, injuries are considered severe when the cervix is involved or when profusely bleeding vaginal lacerations, which can result in hypovolemic shock, are present.30–32

The most common clinical sign of vaginal trauma is vaginal bleeding, which may be masked by spasm of the vagina. Consequently, a speculum examination is essential for women who have sustained pelvic fracture. This examination may occur in the operating suite after pelvic hemorrhage is under control. Evidence from a victim of sexual assault must be retrieved carefully, preferably by a professional trained in evidence collection and forensics, so that all documentation and sample handling is performed appropriately for legal purposes.26,33 Evidence of sperm and seminal plasma still can be obtained up to 48 hours after assault.34 Swabs should be taken of the introitus and rectal cavity. Research suggests that good nursing care can mediate feelings and fears of permanent physical and emotional damage by responding in a supportive manner.33

Management.

Examination under moderate sedation or even general anesthesia may provide a more complete assessment.15,29 More than 75% of upper vaginal lacerations require surgical repair.29 During surgical repair, hypogastric artery ligation may be necessary to control reproductive hemorrhage.29 Interventional angiography for embolization can be performed to avoid retroperitoneal exploration. Packing is an alternative that can be used to control hemorrhage until other organ injuries are ruled out.29,31 Complications of vaginal tears include pelvic abscesses and sepsis. Wounds are often left open to avoid retroperitoneal abscess formation.29,31

TRAUMA TO THE URETHRA

Injury to the female urethra is rarely seen because the urethra is shorter and more mobile than in males.9 When female urethra injury is present, however, it is usually associated with significant pelvic fracture or disruption and injury to the bladder neck and vagina.7 In one study, urethral injury was found to correlate with specific fractures of the pelvis, including inferior rami fractures, widened symphysis, and sacroiliac joint disruption.7 The symphysis pubis widening and fracture of the inferior pubic ramus fractures were also found to be independent predictors of urethral injury, owing to a higher index of suspicion of urethral injuries when these fractures are present.7 Urethral injuries are often the result of straddle- type injuries. Straddle injuries can crush the urethra but not cause pelvic fracture.6 These straddle scenarios are more common in children than in adults.6,35,36 Complete rupture of the urethra is also more common in children because the thin, delicate membrane of the urethra is less elastic than in an adult.35 In children the most likely sites of urethral injury are the prostatic urethra and bladder neck.35,36

The male urethra is divided into two segments: the anterior (distal) and the posterior (proximal). The anterior segment has three anatomic divisions: the glandular, pendulous, and bulbar. The posterior segment comprises the membranous and the prostatic urethra. Pelvic fractures are the most common mechanism of injury to the posterior portion of the urethra.7,36 Pelvic fractures shear the prostate from the urogenital diaphragm, rupturing the ligaments holding the urethra in place and tearing and potentially disrupting the urethra (Figure 26-4).11,36 Anterior pelvic ring disruption with pubic rami fracture results in bladder and urethra injury in either sex due to the shearing forces applied.36 The likelihood of urethral injury increases with open book and vertical shear types of pelvic fractures and should be suspected when a pubic arch is fractured.10

Most anterior urethral injury occurs after a straddle-type injury. Penetrating trauma to the anterior urethra may be produced by gunshot wounds, stab wounds, or self-inflicted instrumentation of the urethra with foreign bodies.5 Power takeoff machinery can also cause penetrating injury to the urethra and is sometimes seen with farming and industrial incidents. In these cases clothing becomes caught in the power belt of a machine, possibly causing injury to the skin of the penis, the scrotum, and the urethra.5,6,23,24

Assessment

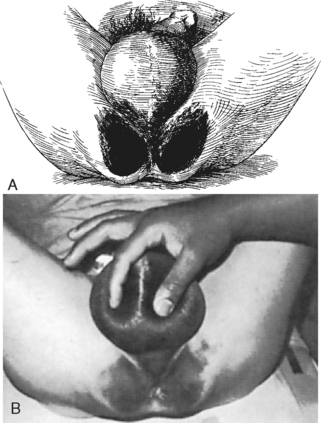

Findings characteristic of urethral injury include identification of blood at the urinary meatus, an inability to void, gross hematuria, pelvic or perineal ecchymosis, perineal or scrotal edema, or a high-riding prostate.5,6,36 A male patient with straddle injury may present with a characteristic butterfly-shaped ecchymotic area beneath the scrotum1,5,6 (Figure 26-5). Urethral blood at the meatus is an inconsistent finding, with only 12% of patients having this clinical finding in one study.7 Because of the high correlation of pelvic fractures with urethral injury, it should be assumed that both male and female patients with pelvic fractures have urethral injury until proven otherwise. RUG is suggested in all patients with blood at the meatus.5

FIGURE 26-5 A, Diagram of a butterfly hematoma. B, Appearance of a patient with perineal butterfly hematoma.

(From Peters P, Sagalowsky A: Genitourinary trauma. In Walsh P, Gittes R, Perlmutter A, et al, editors: Campbell’s urology, 5th ed, vol 1, Philadelphia, 1986, W. B. Saunders.)

In male patients urethral injuries are classified according to location. Table 26-2 lists the classification of urethral injury. In general, urethral injuries below the urogenital diaphragm, involving the bulbous and penile urethra, are classified as anterior urethral trauma. Those above the urogenital diaphragm, toward the bladder neck and involving the prostatic and membranous urethra, are classified as posterior urethral trauma.

TABLE 26-2 Classification of Urethral Injuries

| Grade | Injuries |

|---|---|

| I | Posterior urethra intact but stretched by pelvic hematoma |

| II | Partial or complete postmembranous urethral rupture above intact urogenital diaphragm |

| III | Partial or complete combined anterior/posterior urethral rupture with rupture of urogenital diaphragm |

| IV | Bladder neck injury with extension into the posterior urethra |

| IVA | Base of the bladder injury with periurethral extravasation simulating a grade IV injury |

| V | Partial or complete anterior urethra injury |

Modified from Corriere JN: Trauma to the lower urinary tract. In Gillenwater JY, Grayhack JT, Howards SS et al, editors: Adult and pediatric urology, 4th ed, p 514, Baltimore, 2002, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Posterior urethral injury should be suspected in any patient with a pelvic fracture or separation of the symphysis pubis and in patients in whom a displaced (or high-riding) prostate or soft boggy mass is found on rectal examination.23,36,37 Injury to the membranous urethra is the most common and may extend into the bulbous urethra with disruption of the urogenital diaphragm.7,37 Stretching usually precedes rupture at the bulbomembranous junction.5,6 Any patient with an anticipated urethral tear must have an RUG performed before urethral catheterization.5,18,36 Tears at the urogenital diaphragm demonstrate extravasation into the peritoneum. These are significant tears because cellulitis and sepsis can occur. Urethral stricture may be inevitable with these tears.6,36

Management

The goal of early management is to provide urinary drainage and to prevent associated complications such as worsening injury to the urethra by catherization, strictures, fistula, or infection.5,36,37 The goals of treatment are to maintain patency of the urethra and continence.5,36,37 Treatment options include direct repair, realignment, and nonoperative management with suprapubic cystostomy (SPT) placement.5,36,37 Catheterization by anyone other than the urologist should not be performed if any indication or potential for urethral injury is present. Catheterization can convert an incomplete tear of the urethra to a complete tear, increase the risk of infection, and infect a sterile hematoma.36,37 If the patient can void spontaneously, catheterization is ill advised because any tear is likely partial.6,37 Transurethral catheter placement has traditionally been avoided in posterior urethral injury as identified on RUG; however, one study suggested that catheterization by an experienced urologist with primary realignment of the urethra reduced the need for delayed urethroplasty, and patients with primary realignment had significantly fewer complications, such as stricture, impotence, and incontinence.5,6,36,37

Management of posterior urethral injury may still require SPT to divert urine from the area of injury if a catheter cannot be placed successfully or if the patient is critically ill.36,37 Despite recent advances in surgical management, the most common management of prostatomembranous urethra injury involves SPT placement with delayed urethroplasty.5,36 Use of SPT avoids entry into the pelvic hematoma, thereby decreasing the risk of infection and blood loss and avoiding mobilization of the prostate.36–38 If rectal injuries are present, immediate operation is required. During this time, evacuation of the hematoma with primary urethral realignment over a urinary catheter can be performed.36 Preservation of the bladder neck is essential to maintain continence.37

Acute realignment of injury to the urethra is becoming more common. The procedure has the same incidence of erectile dysfunction and incontinence as SPT alone but decreases the occurrence of stricture.37 Early realignment re-establishes continuity and eliminates the need for delayed urethroplasty and long-term SPT placement. Primary realignment is performed either by endoscopy or fluoroscopy.

Anterior urethral injuries are managed with a transurethral catheter or SPT for approximately 3 weeks. Strictures are likely to occur and require urethroplasty after 3 months.39 RUG is required before urinary catheter or SPT removal to ensure urethral continuity.

Missed urethral injuries in the female patient result in severe complications, which include sepsis and necrotizing infection.38 A delayed diagnosis in the female patient results in incontinence, ureterovaginal fistulae, urethral diverticula, dyspareunia, hematuria, abscess, recurrent urethritis, or cystitis.36,38,40 Treatment for these complications includes urethral catheter stent placement or delayed operative reconstruction.5,36

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree