I. Advanced Trauma Life Support—Initial assessment of an arriving trauma patient has several stages: Primary Survey, Resuscitation, Adjuncts to Primary Survey, Secondary Survey, Adjuncts to Secondary Survey, Reevaluation, and Definitive Care.

A. Primary Survey—The ABCDEs of trauma care are a way to systematically assess a patient’s vital functions in a prioritized manner. Life-threatening conditions should be identified and managed simultaneously.

1. Airway maintenance with cervical spine precautions—Airway compromise in a trauma patient can be an imminently life-threatening condition. It must be evaluated and managed as the first priority. A provider must assume that there is a cervical spine injury in order to protect the spinal cord until a more detailed assessment can be performed. This is especially a concern in patients with an altered level of consciousness and any blunt injury proximal to the clavicles.

2. Breathing and ventilation—Adequate ventilation can be negatively impacted by conditions such as tension pneumothorax, flail chest with pulmonary contusion, massive hemothorax, and open pneumothorax. These disorders should be identified and managed during this stage.

3. Circulation with hemorrhage control—Hemorrhage is the leading cause of preventable death after trauma. Hypotension in the setting of trauma must be considered hypovolemia until proven otherwise. Clinical signs of hypovolemia include decreased level of consciousness, pale skin, and rapid, thready pulses. External hemorrhage should be identified and directly controlled during this stage.

4. Disability: Neurologic status—Rapid evaluation of potential neurologic injury should be performed to include level of consciousness, pupillary size and reactivity, lateralizing signs, and spinal cord injury level (if present).

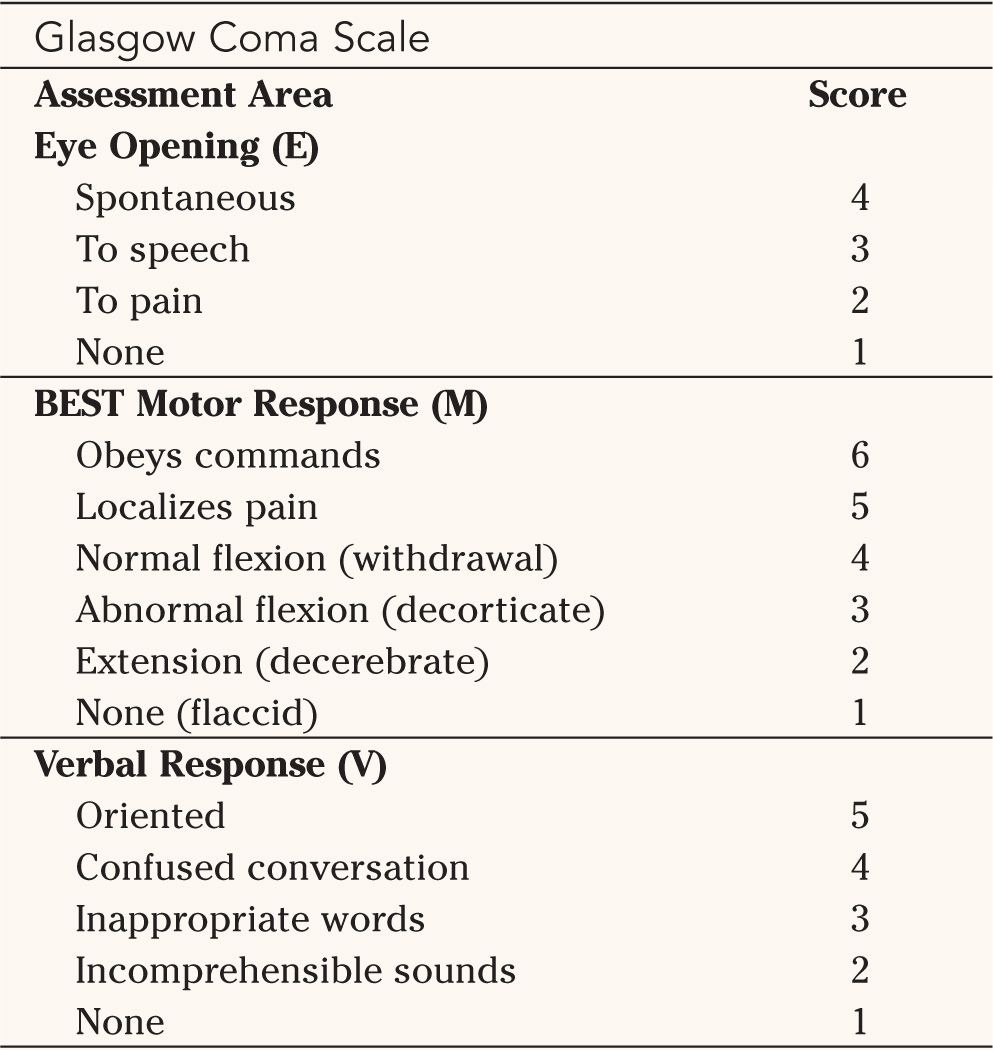

• Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS)—The GCS is a rapid method of determining the level of consciousness of a trauma patient and has prognostic value (Table 1-1). The GCS categorizes the neurologic status of a trauma patient by assessing eye opening response, motor response, and verbal response.

• Possible causes of decreased level of consciousness include hypoperfusion, direct cerebral injury, hypoglycemia, and alcohol/drugs. Immediate reevaluation and correction of oxygenation, ventilation, and perfusion should be performed. Afterward, direct cerebral injury should be assumed until proven otherwise.

Adapted from American College of Surgeons. Advanced Trauma Life Support For Doctors: Student Course Manual. 7th ed. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons, 2004, with permission.

5. Exposure/environmental control: completely undress the patient, but prevent hypothermia—All garments must be removed from the trauma patient to ensure thorough evaluation. Once the evaluation is performed, prevention of hypothermia is critical. Blankets, external warming devices, a warm environment, and warmed intravenous fluids should be used to prevent hypothermia.

B. Resuscitation—In addition to airway and breathing priorities, circulatory resuscitation begins with control of hemorrhage. Initial fluid resuscitation should consist of 2 to 3 L of Ringer’s lactate solution. All intravenous fluids should be warmed prior to or during infusion. If the patient is unresponsive to the fluid bolus, type-specific blood should be administered. O-negative blood may be used if type-specific blood is not immediately available. Insufficient fluid resuscitation may result in residual hypotension in a trauma patient, such as a patient with a pelvic fracture and multiple long bone fractures.

1. Elevation of the serum lactate level (>2.5 mmol/L) is indicative of residual hypoperfusion. Proceeding to definitive fixation of orthopaedic injuries in such a patient with occult hypoperfusion may result in significant perioperative morbidity such as adult respiratory distress syndrome.

C. Adjuncts to Primary Survey

1. ECG

2. Urinary and gastric catheters

3. Monitoring

• Ventilatory rate; arterial blood gas (ABG)

• Pulse oximetry

• Blood pressure

4. X-rays and diagnostic studies

• CXR

• AP Pelvis

• Lateral C-spine—This is a screening exam. It does not exclude a cervical spine injury.

D. Secondary Survey—The Secondary Survey is a head-to-toe examination that begins once the Primary Survey is complete and resuscitative efforts have demonstrated a stabilization of vital functions.

1. History

• AMPLE—AMPLE is an acronym of the following categories that assist in collecting historical information from the patient, family, and/or prehospital personnel.

(a) Allergies

(b) Medications currently used

(c) Past illnesses/Pregnancy

(d) Last meal

(e) Events/Environment related to the injury

2. Physical examination—The head-to-toe examination should occur at this point. The clinician must be sure to inspect the following body regions:

• Head

• Maxillofacial

• Cervical spine and neck

• Chest

• Abdomen

• Perineum/rectum/vagina

• Musculoskeletal

• Neurologic

E. Adjuncts to the Secondary Survey—At this point, specialized diagnostic tests can be performed. These tests may include radiographs of the extremities, CT scans of the head, chest, and abdomen. In addition, diagnostic procedures such as bronchoscopy, esophagoscopy, and angiography can be performed if the patient’s hemodynamic status permits.

F. Reevaluation—Reevaluation is a continuous process during the evaluation and management of a trauma patient. Injuries may evolve in a life-threatening manner, and nonapparent injuries may be discovered.

G. Definitive Care—Definitive care for each injury occurs depending on the priority of the injury and the physiology of the patient. This requires coordinated multidisciplinary care.

II. Shock—Shock is an abnormality of the circulatory system that results in inadequate organ perfusion and tissue oxygenation. Manifestations of shock include tachycardia and narrow pulse pressure.

A. Hemorrhagic Shock—Hemorrhage is the acute loss of circulating blood volume. An element of hypovolemia is present in nearly all polytraumatized patients. Hemorrhage is the most common cause of shock.

1. Classes of hemorrhage

• Class I hemorrhage is characterized by no measurable change in physiologic parameters (heart rate, blood pressure, urine output, etc.) with blood loss less than 15% (<750 mL).

• Class II hemorrhage is characterized by mild tachycardia (>100 bpm), a moderate decrease in blood pressure and low normal urine output (20 to 30 mL per hour). It represents a 15% to 30% blood loss (750 to 1,500 mL).

• Class III hemorrhage is characterized by moderate tachycardia (>120 bpm), a decrease in blood pressure, and a decrease in urine output (5 to 15 mL per hour). The patient is typically confused. It represents a 30% to 40% blood loss (1,500 to 2,000 mL).

• Class IV hemorrhage is characterized by a severe tachycardia (>140 bpm), decreased blood pressure, and negligible urine output. The patient is lethargic. It represents blood loss of over 40% (>2,000 mL).

2. Blood loss due to major fractures—Major fractures may result in blood loss into the site of the injury to such an extent that it may compromise the hemodynamic status of the patient.

• Tibia/humerus—As much as 750 mL (1.5 units) blood loss

• Femur—As much as 1,500 mL (3 units) blood loss

• Pelvic fracture—Several liters of blood may accumulate in the retroperitoneal space in association with a pelvic fracture. The greatest average transfusion requirement occurs with anteroposterior compression pelvic fractures.

B. Nonhemorrhagic Shock

1. Neurogenic—Neurogenic shock can occur as a result of loss of sympathetic tone to the heart and peripheral vascular system in cases of cervical spinal cord injury. Loss of sympathetic tone to the extremities results in vasodilation, poor venous return, and hypotension. Because of unopposed vagal tone on the heart, tachycardia in response to hypotension is not possible. The resultant clinical scenario, called neurogenic shock, is one of hypotension and bradycardia. Assessment of the hemodynamic status may be aided by a Swan-Ganz catheter.

2. Cardiogenic—Cardiogenic shock is myocardial dysfunction that can result from blunt injury, tamponade, air embolism, or cardiac ischemia. Adjuncts such as ECG, ultrasound, and CVP monitoring may be useful in this setting.

3. Tension pneumothorax—Tension pneumothorax is the result of increasing pressure within the pleural space from a pneumothorax with a flap-valve phenomenon. As air enters the pleural space without the ability to escape, it causes a mediastinal shift with impairment of venous return and cardiac output. The clinical scenario involves decreased/absent breath sounds, subcutaneous emphysema, and tracheal deviation. Emergent decompression is warranted without the need for a diagnostic X-ray.

4. Septic shock—Septic shock may occur as the result of an infection. In trauma, this would be more likely in a patient presenting late with penetrating abdominal injuries.

III. Associated Injuries

A. Head Injury—One of the guiding principles in managing a patient with a traumatic brain injury (TBI) is to prevent secondary brain injury from conditions such as hypoxemia and hypovolemia. Patients with head injury are at increased risk of developing heterotopic ossification (HO).

1. Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS)—The GCS (Table 1-1) is employed to stratify injury severity in patients with head injuries (TBI).

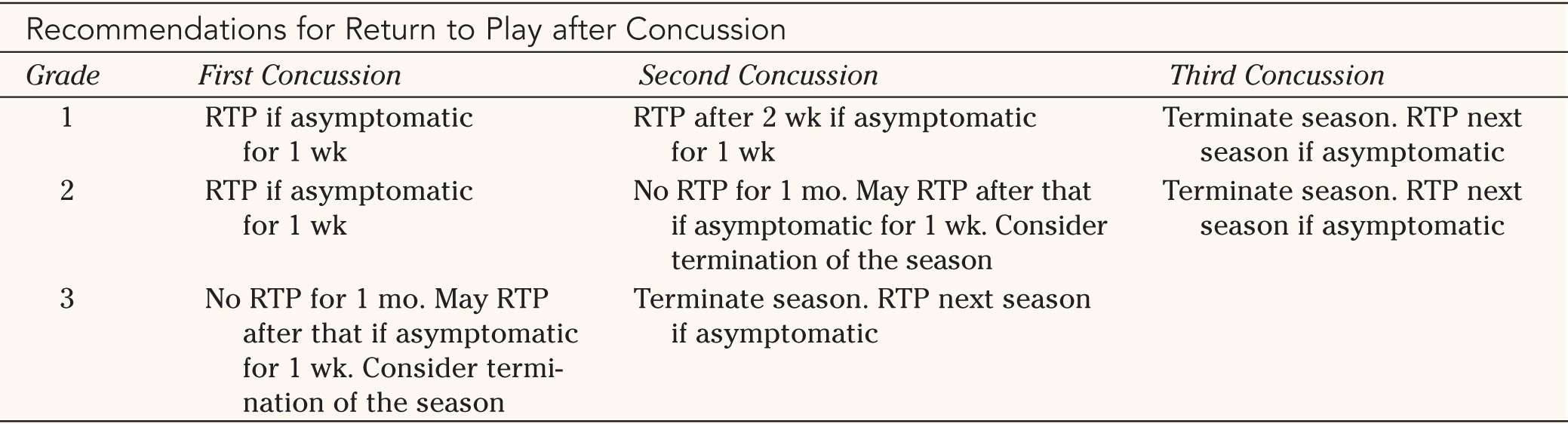

RTP, return to play; “asymptomatic,” no postconcussion syndrome (including retrograde or anterograde amnesia at rest or with exertion.

Adapted from Cantu RC. Posttraumatic retrograde and anterograde amnesia: pathophysiology and implications in grading and safe return to play. J Athl Train. 2001;36(3):244–248, with permission.

• Mild brain injury (GCS, 14 to 15)—Patients with a mild brain injury often have a brief loss of consciousness (LOC) and may have amnesia of the event. Most have an uneventful recovery, but approximately 3% will deteriorate unexpectedly. A CT of the head should be considered if the individual has lost consciousness for more than 5 minutes, has amnesia, severe headaches, GCS of less than 15, and/or a focal neurologic deficit.

(a) Concussion—The term “concussion” is often used to describe a mild TBI.

(b) Sports-related concussion—Return to athletic play after a concussion is guided by recommendations based on grading the concussion and the number of concussions that the individual has sustained (Table 1-2).

• Grade 1 (mild): No LOC. Amnesia or symptoms for less than 30 minutes

• Grade 2 (moderate): LOC for less than 1 minute. Amnesia or symptoms for 30 minutes to 24 hours.

• Grade 3 (severe): LOC for more than 1 minute; amnesia for more than 24 hours; postconcussion symptoms for more than 7 days.

• Moderate brain injury (GCS, 9 to 13)—All of these patients require a CT of the head, baseline blood work, and admission to a facility with neurosurgical capability.

• Severe brain injury (GCS, 3 to 8)—Patients with severe TBI require a multidisciplinary approach to ensure adequate management and resuscitation of other life-threatening injuries and urgent neurosurgical care.

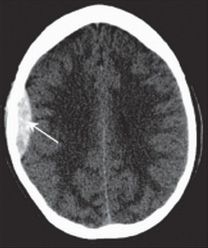

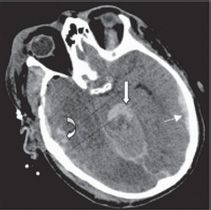

2. Anatomical types of brain injury (Figure 1-1)

• Diffuse brain injury—Diffuse brain injury can be a wide spectrum from mild TBI to a profound ischemic insult to the brain.

• Epidural hematoma—Epidural hematomas are located between the dura and the skull. They usually result from a tear of the middle meningeal artery secondary to a skull fracture.

• Subdural hematoma—Subdural hematomas are located beneath the dura as a result of injury to small surface vessels on the brain. They frequently result in a greater brain injury compared with epidural hematomas.

• Contusion and intracerebral hematoma—Contusion or hematoma within the brain can occur at any location, but they most frequently occur in the frontal or temporal lobes. Contusions can evolve into intracerebral hematomas over time, which require emergent surgical evacuation.

FIGURE 1-1 Computed tomography scans showing (top) epidural hematoma, (center) subdural hematoma (right arrow; this patient also has an intraparenchymal contusion at the curved arrow and a subarachnoid hemorrhage at the center arrow), and (bottom) intracerebral hemorrhage. (From Pascual JL, Gracias VH, LeRoux PD. Injury to the brain. In: Flint L, Meredith JW, Schwab CW, et al., eds. Trauma: Contemporary Principles and Therapy. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2008, with permission.)

3. Management of head injuries

• Primary Survey—Includes an evaluation of airway, breathing, and circulation.

• Neurologic examination.

• Diagnostic procedures—Cervical spine radiograph series, computed tomography (CT) scan for intracranial conditions.

• Intravenous fluids—Maintenance of normovolemia is important following head injury. Hypotonic fluids and glucose are no longer recommended, and hyponatremia can be a concern.

• Hyperventilation—Hyperventilation may be used in select patients under close monitoring to decrease intracranial pressure by decreasing the partial pressure of carbon dioxide and increasing vasoconstriction.

• Medications—A variety of adjunctive medications may be used, but should be administered under consultation with a neurologist.

B. Thoracic Trauma

1. Tension pneumothorax—See description under nonhemorrhagic shock

2. Open pneumothorax—Open pneumothorax is also called a “sucking chest wound.” It occurs when there is a large chest wall defect. This external opening to the environment precludes the chest wall’s ability to generate the negative pressure within the pleural space required to inflate the lung. Treatment is to close the defect with an occlusive dressing that is taped on three sides. This creates a valve that allows air to escape but not to enter the defect in the chest wall.

3. Flail chest—Flail chest is a severe impairment of chest wall movement as a result of two or more rib fractures in two or more places, so that the segment has paradoxical movement during respiration. The underlying pulmonary contusion is the true challenge in this clinical scenario. The pulmonary contusion may cause severe impairment of oxygenation. Management involves ensuring adequate ventilation and appropriate fluid management to prevent fluid overload of the injured lung. Mechanical ventilation may be necessary.

4. Massive hemothorax—Massive hemothorax occurs when large amounts of blood (>1,500 mL) accumulate within the pleural space. This results in lung compression and impairment of ventilation. Urgent, simultaneous restoration of blood volume and drainage of the chest are indicated. Thoracotomy may be required in cases of ongoing blood loss.

5. Cardiac tamponade—Cardiac tamponade is due to fluid accumulation within the pericardial sac. Diagnosis has been described by Beck’s triad: elevated venous pressure (distended neck veins), decreased arterial pressure, and muffled heart sounds. A focused assessment sonogram in trauma (FAST) or pericardiocentesis may be necessary to establish the diagnosis. The pericardiocentesis may be diagnostic and therapeutic.

6. Simple pneumothorax—Simple pneumothorax may be associated with thoracic spine fractures and scapular fractures. Decreased breath sounds and hyperresonance upon percussion are present, and an upright expiratory chest radiograph may aid diagnosis. Treatment is with placement of a chest tube.

7. Pulmonary contusion—Pulmonary contusion can lead to respiratory failure. Treatment includes intubation and assisted ventilation if the patient is hypoxemic.

8. Blunt cardiac injury—Blunt injury to the heart can result in cardiac arrest (“commotio cordis”), cardiac contusion, valvular disruption, or rupture of a cardiac chamber.

9. Aortic disruption—Aortic disruption usually occurs after a high-speed deceleration injury. Radiographic signs include a widened mediastinum, obliteration of the aortic knob, deviation of the trachea to the right, obliteration of the space between the pulmonary artery and aorta, depression of the left main stem bronchus, deviation of the esophagus to the right, widened paratracheal stripe, widened paraspinal interfaces, presence of a pleural or apical cap, hemothorax on the left side, and fractures of the first or second rib or scapula.

10. Diaphragmatic injuries—Diaphragmatic injuries commonly occur on the left side and can be seen on chest radiographs.

C. Abdominal Trauma—Abdominal trauma can occur with varying degrees of frequency depending on whether the mechanism of injury was penetrating or blunt. Blunt injury to the abdomen may result in damage to the viscera by a crush or compression mechanism; the spleen is the most commonly injured organ, followed by the liver. Penetrating injuries such as stab wounds and gunshot wounds impart direct trauma to the viscera by laceration or perforation.

• Diaphragm—Diaphragmatic rupture may be detected on the chest X-ray by elevation or blurring of the hemidiaphragm, an abnormal gas shadow, or nasogastric tube traveling into the chest.

• Duodenum—Duodenal rupture may occur from a direct blow to the abdomen. Retroperitoneal air on CT may signal this injury.

• Pancreas—A pancreatic injury should be suspected if a patient has a persistently elevated serum amylase level.

• Genitourinary (GU)—A GU injury should be suspected with any hematuria. Associated injuries and the mechanism of injury may help in localization of the injury. Renal injuries tend to be associated with direct trauma to the flanks, while lower GU injuries such as urethral and bladder injuries are associated with anterior pelvic ring fractures.

• Small bowel—Small bowel injury should be suspected in a patient with a “seat belt sign” across the abdomen or a flexion-distraction fracture or dislocation of the lumbar spine.

• Solid organ—Traumatic lacerations to the liver, spleen, or kidney can be life threatening due to hemorrhage. Lesser injuries in stable patients may be observed. Urgent celiotomy is necessary in patients with a solid organ injury and evidence of ongoing hemorrhage.

2. Penetrating abdominal injuries—Emergent celiotomy is indicated in any patient with a penetrating abdominal injury with associated hypotension, peritonitis, and/or evisceration.

3. Assessment

• History—Determining the type of accident is important. In automobile accidents, determine whether seat belts or other restraints were being used. In a penetrating injury, identifying the type of weapon used can be useful.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree