1

General Principles of Shoulder Examination

Making an accurate diagnosis of shoulder conditions requires a consideration of the patient’s history, a physical examination, and sometimes imaging studies. This chapter will discuss what we consider important principles when examining the shoulder complex. In some cases it may not be necessary to fulfill all the components of the “ideal” examination, but a thorough history and physical examination are particularly helpful when evaluating a patient with shoulder and upper extremity complaints. This chapter will also delineate some of the findings that can be discovered simply by observation of the patient.

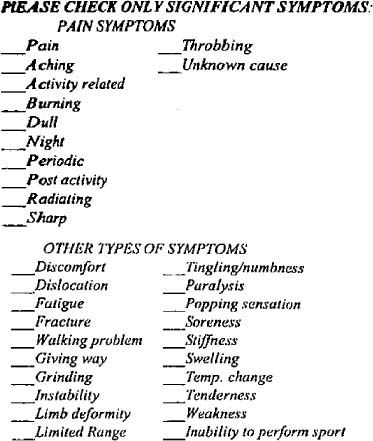

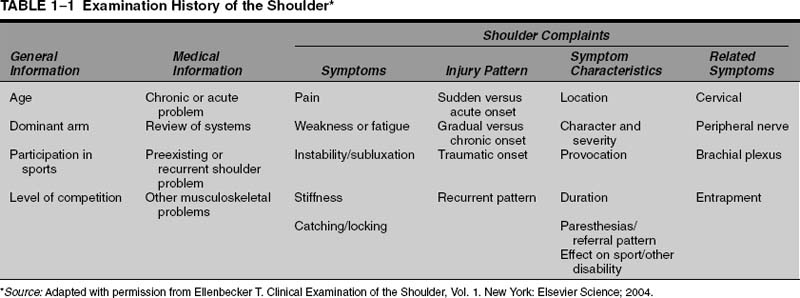

There are several important aspects of the history that should be established in each patient (Table 1-1). The dominance of the extremity can have significant implications for treatment. Many patients will live with a disability in the nondominant extremity that would be unacceptable in their dominant shoulder. A good example is the professional baseball player who has a traumatic shoulder instability in his nondominant arm that does not affect his performance; if the instability was in the player’s dominant extremity, then surgery would more likely be necessary. It is often helpful to have patients fill out a standardized history form to obtain information about their symptoms (Fig. 1-1).

The etiology of the onset of the problem is particularly important, specifically whether it was insidious or if there was a history of trauma. If the patient had no trauma, it is important to find out if he or she had tried any new activities in the days preceding the onset of pain. New activities often will initiate a rotator cuff tendinitis but also can aggravate a preexisting arthritis of the shoulder. A history of a “pop” followed by ecchymosis suggests a tendon tear, such as the long head of the biceps tendon or the pectoralis major tendon.

The severity of the symptoms at onset is important. If the pain begins insidiously and is not very severe at the onset, then certain diagnoses may be considered over others. A sudden onset of severe pain without trauma could be brachial neuritis, a pinched cervical nerve, shingles, acute calcific tendinitis, a pathological fracture, or acute frozen shoulder. Slower onset of pain is typical of rotator cuff tendinitis, idiopathic frozen shoulder, cancer, and a multitude of other etiologies. If there is an acute event, the signs of a more serious injury include the inability to continue the activity or sport. Pain that makes a patient nauseous typically reflects a more severe problem.

FIGURE 1-1 Figure of standardized symptom checklist used in the office to help establish the nature and quality of the patient’s complaints.

Weakness of the shoulder or upper extremity is considered a neurologic complaint until proven otherwise. Weakness can be due to intrinsic shoulder problems, but it is imperative that the practitioner be considering other possible etiologies or combinations of etiologies causing the weakness. We have had several patients present to us who had seen physicians and given a diagnosis of rotator cuff dysfunction but who had weakness of the shoulder as a primary complaint. Both had no history of trauma, and both had a history of painless weakness. One example was a young woman in her 20s with arm weakness who had a cervical spine tumor. Another example was a more mature patient in his 60s who presented with similar insidious onset of weakness and who had Lou Gehrig’s disease (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis). Weakness secondary to pain is common, but a complete upper extremity neurologic evaluation is recommended to make sure there is not a neurologic etiology.

Parasthesias have a neurologic etiology in most cases, and the patient should be asked about the distribution, duration, and severity of the sensory changes. Shoulder problems do not intrinsically cause parasthesias in most instances, and another source of the abnormal sensations should be pursued. Intrinsic shoulder problems that cause parasthesias include nerve entrapments in throwing athletes or workers.1

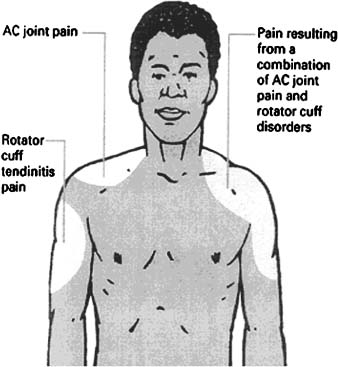

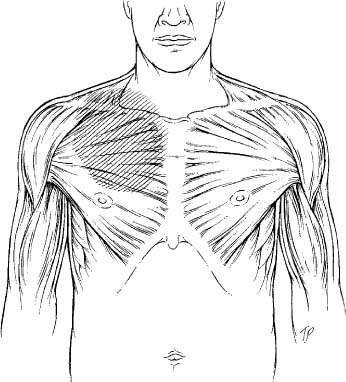

If the patient complains of pain, the distribution of the pain is important. Patients with acromioclavicular (AC) joint pain will typically (but not always) point right at the AC joint, whereas rotator cuff pain tends to be more global or into the deltoid. Gerber et al injected saline into the AC joint of volunteers, and the pain distribution was at the AC joint, with radiation into the trapezius.2 Injection of saline into the subacromial space produced classic rotator cuff pain in the deltoid region. In some individuals with both AC arthritis and rotator cuff tendinitis, the pain may be present in both areas (Fig. 1-2). Inflammation and stiffness of the shoulder can both cause the pain to radiate down the arm; however, radiation down the arm to the hand should raise the suspicion of cervical disk disease.

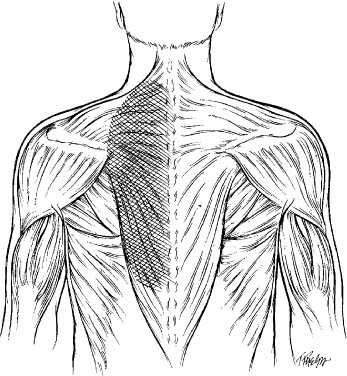

Pain in the medial shoulder blade area is common, and the differential diagnosis includes thoracic outlet syndrome, a lung process, a rib problem, cervical disk disease, and, rarely, degenerative or pathological processes in the thoracic spine (Fig. 1-3). Medial shoulder blade pain may be due to incorrect use of the shoulder blade secondary to an intrinsic problem in the shoulder. In this case the patient is using the muscles of the shoulder blade to elevate the shoulder, and the increased or abnormal stress causes muscle fatigue and pain; however, the diagnosis of muscle pain in the medial scapular region should be a diagnosis of exclusion once other conditions have been ruled out.

Chest or rib pain not directly in the shoulder itself should prompt the examiner to inquire about shortness of breath or symptoms of angina. Anginal pain may radiate into the neck and down the arm, and the patient may place his or her hand over the region of the heart as the source of the pain; this is referred to as the “Levine sign” (Fig. 1-4).3 Pain along the chest and medial to the midclavicle may be seen with sternoclavicular problems, but the differential diagnosis for anterior chest wall pain more typically includes thoracic outlet syndrome or cervical disk disease (Fig. 1-5). Pain in the axilla or ribs below the shoulder is uncommon, but the differential diagnosis includes a pathological rib process, a pulmonary problem, or thoracic outlet syndrome.

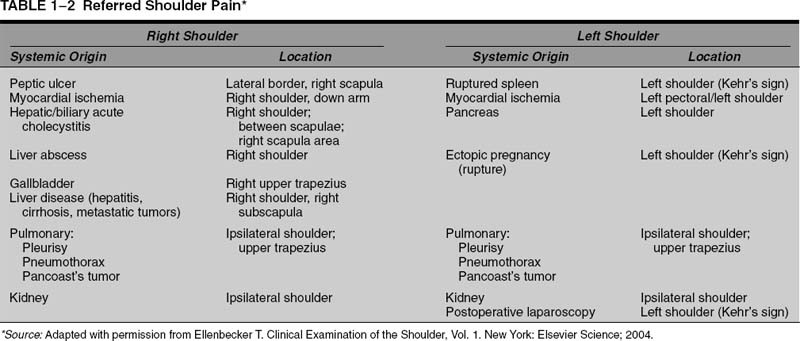

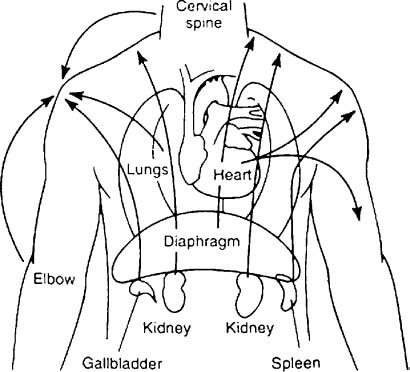

Referred pain to the shoulder from visceral causes has been reported (Table 1-2). Although the classic teaching is that gallbladder or liver disease can cause shoulder pain, the pain typically is located near the posterior shoulder blade and not in the shoulder (Fig. 1-6). Cardiac disease can cause shoulder and arm pain, and Horne et al have shown that angina pain radiated into the shoulder and arm in 66% of patients experiencing their first case of myocardial infarction.4

FIGURE 1-2 AC joint pain tends to be on the top of the shoulder and radiates into the trapezius region, whereas subacromial irritation tends to be present in the deltoid and lateral shoulder. (Adapted with permission from McFarland EG, Hobbs WR. The active shoulder: AC joint pain and injury. Your Patient Fitness 1998;12(4):23–27.)

FIGURE 1-3 Drawing of typical location for posterior thorax pain as a result of cervical spine pathologies.

FIGURE 1-4 The Levine sign was described as a clenched fist over the chest and was felt to be indicative of angina. (Adapted with permission from Edmondstone WM. Cardiac chest pain: does body language help the diagnosis? BMJ 1995;311(7021):1660–1661.)

FIGURE 1-5 Pain along the anterior chest wall and medial to the clavicle is typically due to cervical spine (cervical level 4) pathology or due to thoracic outlet problems.

Pain in multiple areas, particularly when not associated with any specific pattern, can be due to a severely inflamed shoulder. Included in the differential diagnosis of diffuse pain should be connective tissue disorders such as polymyositis, Lyme disease, medication myalgias, and fibromyalgia.

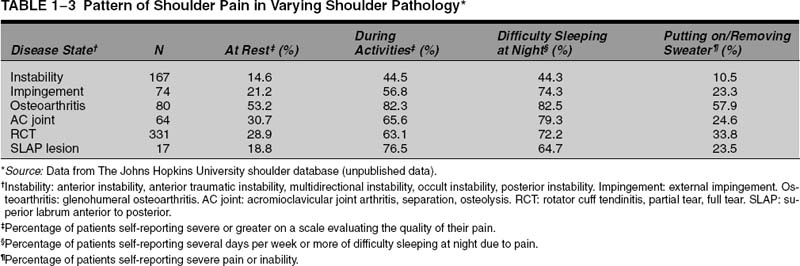

What makes the pain worse can be helpful in determining the diagnosis, but this is not diagnostic for any one entity (Table 1-3). Pain at night is a worrisome sign, especially if it occurs without the patient rolling over or lying on the shoulder. Progressive pain is also a red flag, especially if it continues to increase despite treatment. Pain that progresses to the need for narcotics suggests that there may be a more serious etiology of the pain.5

FIGURE 1-6 Visceral pain can be referred to the shoulder region in a variety of nonspecific patterns. (Adapted with permission from Ellenbecker T. Clinical Examination of the Shoulder, Vol. 1. New York: Elsevier Science; 2004.)

Which motions aggravate the pain can be of some assistance in making the diagnosis. Pain over shoulder level, especially into the deltoid or down the arm, can be indicative of rotator cuff disease, but it also can be seen with stiff shoulders. Patients with rotator cuff disease may have pain with motions behind the back, but patients with a frozen shoulder also may complain of this problem. In our analysis of patients by diagnostic group, we found that patients with rotator cuff had symptoms most often associated with using their back pocket, using their arm at shoulder level, and using their arm overhead. In contrast, patients with SLAP (superior labrum anterior to inferior) lesions showed difficulty performing most activities, regardless of degree of flexion at the shoulder (Table 1-4).

What makes the pain better may give some clues to the etiology of the pain, but this information will not typically make the diagnosis. Pain made better with antiinflammatory agents usually indicates that the pain is not severe. Improvement with ice may indicate an inflammatory condition, but this finding is nonspecific. Improvement with massage may indicate a muscular condition, but this also is not diagnostic.

In patients who have an injury, the exact mechanism of injury can provide clues to the nature of the injury. Though not diagnostic, certain injury mechanisms are frequently associated with one injury type (Table 1-5). A fall onto the shoulder can cause fractures, rotator cuff tears, and SLAP lesions. A fall with the arm extended and externally rotated can result in dislocations or tears of the subscapularis tendon. Certain sports are associated with specific injuries, depending on the mechanism (Table 1-6). A tearing sensation that occurs when bench pressing or doing dips or pushups can indicate a tear of the pectoralis major tendon. An axial load on a slightly abducted arm can cause posterior instability. Some axial loads can cause fractures or chondral contusions. Statistical analysis of our patients revealed that shoulder instability is most often associated with sports-related injury, whereas rotator cuff tears present more frequently with insidious onset or resulting from a fall (Table 1-7).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree