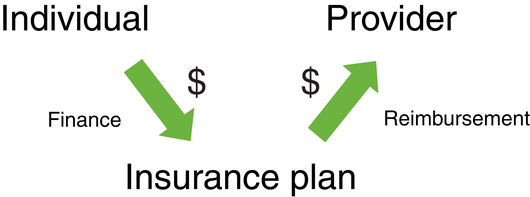

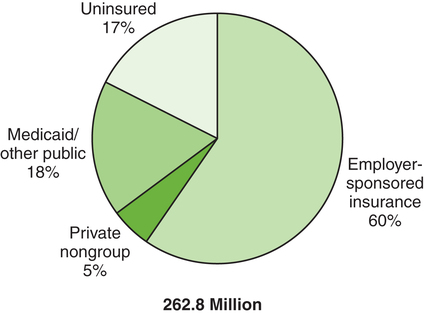

After reading this chapter, the reader will be able to: Balanced Budget Act of 1997 (BBA) Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act (CHIPRA) Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes diagnostic-related groups (DRGs) durable medical equipment (DME) employer-sponsored health insurance health maintenance organization (HMO) independent practice association (IPA) model managed care organization (MCO) Medicare Modernization Act (MMA) Medicare Part A—Hospital Insurance Medicare Part B—Supplementary Medical Insurance Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act preferred provider organization (PPO) prospective payment system (PPS) resource-based relative value scale (RBRVS) resource utilization groups (RUGs III) usual, customary, and reasonable (UCR) Health is unpredictable; it is uncertain if or when a person will become sick or require health care services.1 The types of health care services a person needs vary greatly from an appointment in a doctor’s office to a lengthy hospitalization in an intensive care unit (ICU). The need for catastrophic health care services could obliterate a family’s or a person’s finances. Therefore people in the United States purchase health insurance to minimize risk, defined in health care as the probability of a financial loss. This provides “peace of mind” against the high costs of health care. Health insurance refers to the variety of policies that can be purchased to cover certain health-related services and goods. Policies range from those that cover the costs of medical, surgical, and hospital expenses to those that meet a precise need, such as covering the costs of long-term care. Typically, to become insured (covered by the policy), a subscriber (individual who purchases the policy) purchases a health insurance plan from an insurer (health insurance company). The subscriber purchases a range of benefits and benefit levels, which are available for a defined period of time, usually 1 year. Benefits are described as covered services or those services that are reimbursed by the insurance policy. Some typical covered medical services include inpatient hospital services, outpatient surgery, physician visits (in the hospital), office visits, skilled nursing care, medical tests and x-ray examinations, prescription drugs, physical therapy, and maternity care. Often coverage for some goods, such as durable medical equipment (DME), is limited or not provided under the health insurance plan; in this case the patient is completely responsible for payment. DME is medical equipment (such as a wheelchair, hospital bed, or ventilator) that a practitioner may prescribe for a patient’s use over an extended period.2 Health insurance companies do not finance health care. They were established to offer policies that assume risk and to process health insurance claims; both tasks complicated health care transactions and added administrative expenses to the cost of providing health care. Who then finances health care—in other words, who pays for these health insurance policies? Figure 6-1 illustrates the relationship between financing and reimbursement in health care and how this has changed dramatically in the United States. In the traditional or first-party system, the individual seeking health care (first party) paid the provider (second party) directly. As health care services and costs increased, health insurance companies and the policies they offered became extensive (see earlier discussion). Individuals could no longer afford to pay for the services or even the policies directly. Employers and the government established programs to contribute to the cost of health insurance. The system shifted to the current or third-party system, in which health insurance companies (third party) are paid for their policies and then pay for the health care services. Fundamentally, therefore, health care is financed by the individual directly, the employer, or the government. Figure 6-2 illustrates the percentage of individuals who have insurance provided by each of these sources. Note that this figure is for the nonelderly population, so the impact of Medicare is limited. In addition, note the significant percentage of individuals who are uninsured and the increasing trend for this group. Although health care services may be available, not everyone has access to health care, defined as the ability to receive health care services when needed, because of the way the health care system is organized and financed in the United States. Under the first source of financing health care (private nongroup in Figure 6-2), the individual purchases a health insurance policy directly from a health insurance company. Acquiring health insurance this way is expensive and not commonly done. In this direct pay approach the individual pays the premium, or cost of the insurance, out of pocket. The second and most common method of financing health care is in an employment-based arrangement (see Figure 6-2). Most employees purchase health insurance through their employers. This is known as employer-sponsored health insurance or group insurance. Employers offer health insurance coverage as a benefit for their employees, typically those who work full time. Employers are given tax incentives to offer health insurance as a benefit. Essentially, in the group model both employees and employers finance health care. The employers agree to pay all or a certain portion of the premium of a health insurance plan. The employee pays the premiums using payroll deductions combined with the employer’s contributions. Each year a period is designated as open enrollment, during which an employee has the opportunity to switch to a new health insurance plan based on individual and family needs and health insurance plans available. Once a selection has been made, the subscriber is locked into the choice for a defined period of time, usually 1 year. Premium costs vary depending on the type of health plan or level of benefits purchased. In addition to the premiums, subscribers are responsible for financing other health care costs incurred at the point of service depending on the type of health insurance plan purchased; usually these costs are paid out of pocket. These cost commitments can include deductibles, copayments (“copays”), and co-insurances. A deductible is the amount that the subscriber incurs before a health insurer will pay for all or part of the remaining cost of the covered services. Deductibles may be either fixed dollar amounts, such as $500, or the value of a particular service, such as 2 days of hospital care. Usually deductibles are linked to some defined time period (e.g., a calendar year) over which they must be incurred. Frequently the insured individual can choose a higher deductible to reduce the monthly premiums for the health insurance policy. Copayments are flat dollar amounts (e.g., $40) a subscriber has to pay for specific health services (e.g., physician office visit) at the time of service. Co-insurance, usually expressed as a percentage, is a cost-sharing obligation under a health insurance policy. The subscriber is required to assume responsibility for a percentage of the costs of the covered services (commonly 20%). Box 6-1 provides an example of how these expenses would apply with a typical office visit. The third and a major source of financing health care is the government (see Figure 6-2). The federal government finances the Medicare program, and the federal and state governments finance Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) for each state. In addition, the government funds research efforts through the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Public Health Service, and initiatives. Tax dollars collected from individuals and corporations are allocated to finance these programs and services. Worth highlighting, some individuals with low incomes who do not have access to employer-based or other insurance gain coverage through publicly funded programs such as Medicaid and CHIP. Yet 45 million nonelderly people, 17% of the total nonelderly population in the United States, still lacked health insurance in 2007 (see Figure 6-2). Medicare is the federally funded health insurance program that was enacted (as an amendment to the Social Security Act) in 1965 to cover the elderly population (age 65 years and older), persons with end-stage renal disease, and those who are disabled and entitled to Social Security benefits. Medicare provides coverage for over 43 million beneficiaries.3 This is an entitlement program—that is, Americans 65 years of age and older who have contributed to Medicare through taxes or meet other disability eligibility requirements have the right to the benefits of Part A of this program. An individual entitled to Medicare is known as a beneficiary.4 Medicare Part B—Supplementary Medical Insurance (SMI) is a voluntary program. Individuals entitled for Medicare Part A have the option to purchase Medicare Part B. Medicare Part B is funded from beneficiary premium payments, matched by general federal revenues. According to CMS, the premium for Part B is increased each year, if necessary, to fund approximately 25% of the projected cost of Part B; in 2010, most beneficiaries will pay the 2009 Part B premium of $96.40, even though the 2010 standard monthly Part B premium is $110.50.5 Medicare Part B helps pay for physician services, outpatient hospital services, select home health services, medical equipment and supplies, and other health services, such as physical therapy.

Financing Health Care and Reimbursement in Physical Therapy

Discuss the reimbursement process in health care

Discuss the reimbursement process in health care

Differentiate between retrospective and prospective reimbursement methods

Differentiate between retrospective and prospective reimbursement methods

Discuss how risk and health insurance are related

Discuss how risk and health insurance are related

Differentiate between indemnity health insurance and managed care plans

Differentiate between indemnity health insurance and managed care plans

Differentiate among Medicare, Medicaid, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP)

Differentiate among Medicare, Medicaid, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP)

Discuss how health care is financed

Discuss how health care is financed

Define how managed care organizations control health care costs

Define how managed care organizations control health care costs

State current trends in health care spending

State current trends in health care spending

Discuss the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 (BBA) and its impact on physical therapy reimbursement

Discuss the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 (BBA) and its impact on physical therapy reimbursement

Health Insurance

Financing Health Care

Medicare

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Musculoskeletal Key

Fastest Musculoskeletal Insight Engine