Femoroacetabular Impingement: Arthroscopic Management of the Proximal Femur

Christopher M. Larson

Rebecca M. Stone

Introduction

Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) is a disorder characterized by abnormal conflict between the pelvis and proximal femur (1,2,3,4,5,6). Cam-type impingement is traditionally described as an offset pathomorphology of the femoral head–neck junction (1,2,3,4,5,6). Although the primary focus of cam-type FAI in the literature focuses on developmental decreased femoral head–neck offset, proximal femoral impingement can also be secondary to isolated femoral neck retroversion, coxa vara, slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE), deformity secondary to femoral neck fractures, or trochanteric impingement which is classically seen in the setting of Legg–Calvé–Perthes disease (LCP) (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8). The following chapter will focus on the indications and specific surgical techniques for arthroscopic management of the proximal femur in the setting of FAI. Anatomy and pathomechanics, epidemiology, typical patient presentation, appropriate imaging, and outcomes for arthroscopic treatment of cam-type FAI will also be discussed.

Anatomy and Pathomechanics

Proximal femoral impingement is typically the result of an aspheric femoral head and/or insufficient head–neck offset. Although this was originally termed a “pistol-grip” deformity and felt to be secondary to a mild or subclinical slipped capital epiphysis, further research has shown that this may be the result of increased lateral extension of the epiphysis (6). The pathogenesis of cam-type FAI is unclear. It has been suggested that excessive loading secondary to athletic activities during adolescence may result in adaptive physeal remodeling and bony apposition at the head–neck junction leading to this asphericity (9). This has been our observation in young adolescent athletes involved in high impact, cutting and pivoting activities. We have seen this most frequently in young male and female butterfly hockey goalies, who find themselves in repetitive high loading and extreme flexion, abduction, internal rotation positions at a young age. There also appears to be a genetic component as one study found that siblings of patients with cam-type FAI had a relative risk of 2.8 of having the same deformity compared to normal controls (10).

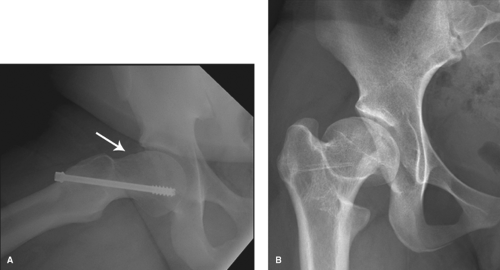

Although cam-type FAI is typically located anteriorly, it is important to recognize that there is much variability in the size and extent of these lesions. They can be primarily anterior, superior, posterior, inferior, or circumferential in some cases. The location has importance with respect to motion limitations and respective pain-generating activities, as well as with regard to choosing the most appropriate surgical approach when indicated. Cam-type FAI can also be seen in other situations. Residual deformity secondary to prior SCFE, LCP, or femoral neck fractures can lead to cam-type FAI (5,7,8) (Fig. 47.1). Excessive coxa vara and relative femoral neck retroversion can also contribute to proximal femoral impingement. In some situations, the greater trochanter can impinge against the pelvis and this is most frequently seen in the setting of LCP (5).

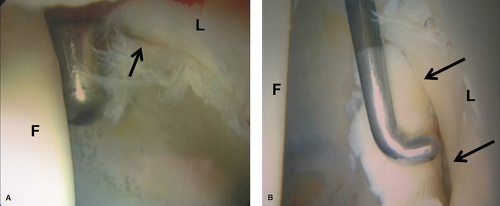

The abnormal femoral head–neck junction with its increased radius creates intra-articular damage as it is forced into the acetabulum during impingement range of motion (1,2,4,5,6,9). Isolated cam-type FAI generally produces shear forces, resulting in eventual disruption of the acetabular articular cartilage from the labrum (1,2,4,5,6,9). This labrochondral disruption may be partial thickness early on and can progress to large full-thickness chondral delaminations and eventual full-thickness exposed lesions over time (Fig. 47.2). It has been suggested that FAI may be a significant etiology leading to hip osteoarthritis (OA) (2,5). Many individuals with FAI, however, have a combination of cam- and pincer-type FAI and damage resulting from both mechanisms may be appreciated in these situations.

Epidemiology

The reported prevalence of radiographic FAI is variable depending on the specific patient population being studied

(10,11,12,13,14,15,16). One study evaluated radiographs of 817 patients of Asian descent with documented OA and reported only a 0.6% prevalence of FAI (14). Another study, however, looking at a cohort of 3,620 patients with OA from a Danish database reported a prevalence of cam-type FAI in 19.6%, and mixed-type FAI in 2.9% of males (15). More specifically, cam-type FAI has been reported to be most common in young athletic males (2,5,11,12,13). One study evaluated 200 asymptomatic Canadian volunteers with a mean age of 29 years, and found a 14% prevalence of cam-type FAI with 79% of those being male (11). Another study looked at 2,081 healthy young adults and found a 35% and 10% prevalence of cam-type FAI in males and females, respectively (13). It has been our observation that the prevalence of FAI and in particular cam-type FAI is higher in a young athletic population. In fact, one study evaluated radiographs of 34 athletes who presented with long-standing adductor-related groin pain and reported a radiographic prevalence of FAI in 94% of these athletes (16).

(10,11,12,13,14,15,16). One study evaluated radiographs of 817 patients of Asian descent with documented OA and reported only a 0.6% prevalence of FAI (14). Another study, however, looking at a cohort of 3,620 patients with OA from a Danish database reported a prevalence of cam-type FAI in 19.6%, and mixed-type FAI in 2.9% of males (15). More specifically, cam-type FAI has been reported to be most common in young athletic males (2,5,11,12,13). One study evaluated 200 asymptomatic Canadian volunteers with a mean age of 29 years, and found a 14% prevalence of cam-type FAI with 79% of those being male (11). Another study looked at 2,081 healthy young adults and found a 35% and 10% prevalence of cam-type FAI in males and females, respectively (13). It has been our observation that the prevalence of FAI and in particular cam-type FAI is higher in a young athletic population. In fact, one study evaluated radiographs of 34 athletes who presented with long-standing adductor-related groin pain and reported a radiographic prevalence of FAI in 94% of these athletes (16).

History and Physical Examination

A thorough history and physical examination for patients presenting with hip joint-related complaints can help to verify the underlying pathomechanics at work. The typical history for a patient presenting with symptomatic cam-type FAI is the insidious onset of groin or deep lateral hip pain. Less commonly a traumatic episode, such as a hip subluxation, dislocation, or torsional event sustained during sporting activities, is the presenting complaint. The classic patient with cam-type FAI is a young male who develops pain with athletic activity and in particular cutting and pivoting sports. Patients are generally in their second, third, and sometimes fourth decades when they initially present with hip-related complaints. This can be variable, however, depending on the activity level and degree of cam-type FAI and associated acetabular pathomorphology. These episodes are often initially misdiagnosed as recurrent “hip flexor” injuries. Patients who present later in life with cam-type FAI typically have more advanced degenerative changes. Initially there may be complaints of nonlimiting, sharp, intermittent activity-related pain, which progresses to limiting pain during and after activity. Torsional activities, such as sports involving directional changes or getting in and out of a car, are generally more problematic than frontal plain activities. There may be complaints of aching pain with prolonged sitting or flexion/abduction-based activity. A history of hip “inflexibility” or inability of the patient to sit with their legs crossed or in a figure of four positions may also be elicited. When symptoms progress to aching pain at rest and in particular while sleeping more advanced degenerative changes may be present. In some cases there may be a history of surgery for a femoral neck fracture, SCFE, or LCP. If a history of significant hip or knee pain as a child or adolescent without treatment is elicited, this may be consistent with previously undiagnosed LCP or SCFE, respectively.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree