Femoroacetabular Impingement—Arthroscopic Management of the Acetabular Labrum

Marc Safran

Eli Chen

Introduction

In a field traditionally dominated by developmental dysplasia and degenerative disease, prearthritic conditions of the hip have moved to the forefront. Hip preservation techniques, that is, the maintenance of normal hip function in the setting of overuse or other early-stage pathology, have garnered recent interest from the orthopedic surgery community at large, including specialists in pediatrics, adult reconstruction, trauma, and sports medicine. In particular, femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) and its associated labral and chondral pathology represent the main focus of attention. Hip arthroscopy is increasingly being performed in concert with this movement, in part because of the minimally invasive nature and reduced morbidity of the technique as well as the ability to visualize the joint surfaces. Early results have shown good success with this approach and continued advances in imaging, instrumentation, and surgical techniques, as well as enhanced understanding of hip biomechanics and pathophysiology have expanded surgical indications. Leading this change in surgical techniques is our better understanding of the labrum’s function as well as how its anatomy influences our surgical techniques. Although initially thought to be mainly a static stabilizer of the hip joint the labrum plays a critical role in the maintenance of fluid seal within the hip joint minimizing friction of the cartilage surfaces as well as providing negative seal to the joint (1,2,3,4,5,6). In regard to structure, its distinct labral–chondral junctions between the anterior and posterior aspects of the junction as well as its triangular shape have implications in regard to how the labrum is taken down and repaired (7,8,9,10,11,12,13). This chapter discusses current literature on arthroscopic management of labral pathology, indications, and surgical techniques.

Classification of Labral Pathology

Given the important role of the labrum in maintaining normal biomechanics of the hip joint, it is critical during FAI surgery to address labral pathology. Several classification systems have been devised to describe labral pathology. Czerny et al. (14) described a classification system on the basis of magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) findings, with a subset of patients undergoing subsequent surgery. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with addition of arthrography improved accuracy to 91% from 36% over conventional MRI. Staging was on the basis of penetration of contrast material into the labral substance, with further subclassification of thickening and presence of labral recesses.

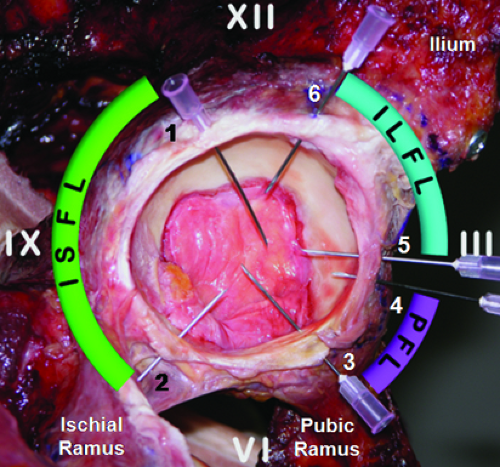

Evaluation of the joint through diagnostic arthroscopy and range of motion allows for direct visualization of hip pathology, including dynamic testing of impingement. Several classification systems for labral pathology have been proposed, with no consensus as to which has the best prognostic value. Tears of the labrum have been classified by location, dividing the acetabulum in three quadrants or by defining the acetabulum as a clockface. In the clockface model, the transverse acetabular ligament is defined as the 6 o’clock position, with anterior designated as 3 o’clock regardless of whether it is a right or left hip (Fig. 46.1). Cadaveric mapping of the capsular ligaments has shown distinct and consistent arthroscopic locations, associated with clearly identifiable landmarks in the central and peripheral compartments (15).

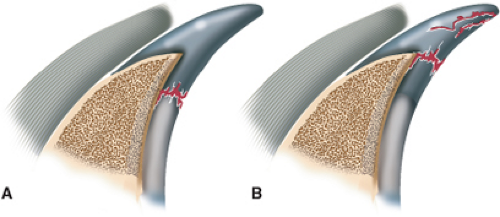

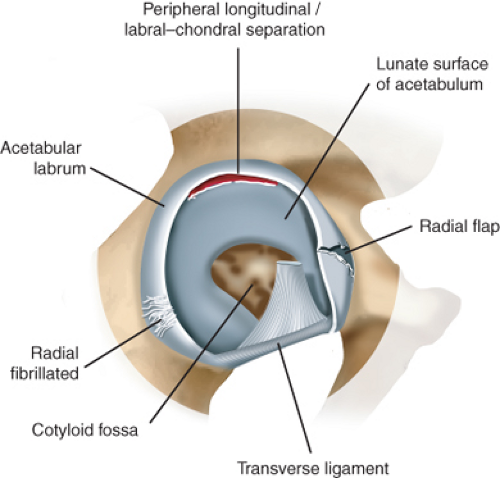

Other classification systems are based on histologic appearance, gross appearance, morphology, or suspected etiology of pathology. Seldes et al. (2) divided tears into two groups on the basis of histologic evaluation (Fig. 46.2). The first type is a detachment of the labrum from the articular surface (labral–chondral separation); the second type is intrasubstance injury, composed of one or more cleavage planes within the body of the labrum. Lage et al. (16) described an arthroscopic classification system, similar to that used in meniscal tears (Fig. 46.3). Tears were subdivided into four types either by etiology (traumatic, degenerative, idiopathic, and congenital) or by morphology (radial flap, radial fibrillated, longitudinal peripheral, and unstable). Of the morphologic variants, the first type (radial flap) was the most common (56.8%), involving a disruption at the free margin of the labrum. The radial fibrillated tears (21.6%) were associated

with degenerative articular cartilage. Longitudinal peripheral tears (16.2%) were present at the junction of the acetabular rim. The fourth type, the abnormally mobile tear, was found in 5.4% of patients. McCarthy et al. (4) classified labral tears in conjunction with adjacent cartilage damage. Stage 0 involves a contusion of the labrum with adjacent synovitis. Stage 1 involves a discrete tear of the labrum without involvement of femoral or acetabular cartilage. Labral tears that include cartilage damage of the femoral head are described as stage 2, whereas involvement of the acetabular cartilage is described as stage 3. This stage is further subdivided based on the size of the articular cartilage lesion; less than 1 cm is defined as stage 3A whereas greater than 1 cm is stage 3B. Labral tears seen in the setting of diffuse arthritic changes are described as stage 4.

with degenerative articular cartilage. Longitudinal peripheral tears (16.2%) were present at the junction of the acetabular rim. The fourth type, the abnormally mobile tear, was found in 5.4% of patients. McCarthy et al. (4) classified labral tears in conjunction with adjacent cartilage damage. Stage 0 involves a contusion of the labrum with adjacent synovitis. Stage 1 involves a discrete tear of the labrum without involvement of femoral or acetabular cartilage. Labral tears that include cartilage damage of the femoral head are described as stage 2, whereas involvement of the acetabular cartilage is described as stage 3. This stage is further subdivided based on the size of the articular cartilage lesion; less than 1 cm is defined as stage 3A whereas greater than 1 cm is stage 3B. Labral tears seen in the setting of diffuse arthritic changes are described as stage 4.

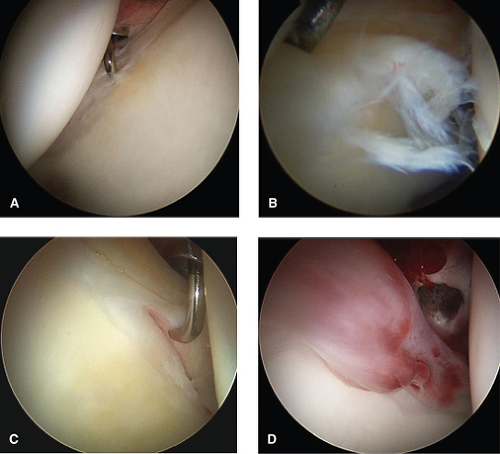

Recently, the Multicenter Arthroscopic Hip Outcomes Research Network (MAHORN) group has proposed a classification system to study labral tears to determine if there is a prognostic distinction between different types of tears with regard to outcomes (Table 46.1; Fig. 46.4). This

classification system takes into consideration the overall appearance and morphology of the labrum, as well as pathologic changes to the labrum. Here, in addition to describing tears, intrasubstance changes within an otherwise intact labrum are characterized. Although still in its infancy, the goal of this classification system is to establish parameters for management of tear patterns as well as more subtle changes in the labrum with regard to clinical outcome.

classification system takes into consideration the overall appearance and morphology of the labrum, as well as pathologic changes to the labrum. Here, in addition to describing tears, intrasubstance changes within an otherwise intact labrum are characterized. Although still in its infancy, the goal of this classification system is to establish parameters for management of tear patterns as well as more subtle changes in the labrum with regard to clinical outcome.

Table 46.1 Multicenter Arthroscopic Hip Outcomes Research Network (MAHORN) Classification System for Labral Tears | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

Currently, the senior author uses the Seldes classification system clinically and the MAHORN system for outcomes analysis. The former is a practical guide for the treatment of labral tears. Labral tears at the labral–chondral junction have the ability to heal through the blood supply of the acetabulum, whereas intrasubstance labral tears are usually treated with partial labrectomy, as the limited-to-absent blood supply makes healing of an attempted repair unlikely. This distinction determines whether a tear is suitable for repair, or better treated with debridement. The MAHORN system is being used to document labral findings at the time of operation to assess long-term outcomes. At present, it is unclear whether a grossly deformed or degenerative labrum is able to maintain its physiologic function, or whether it is predisposed to tearing and clinical sequelae. Intraoperative assessment in the context of clinical history is presently being used to determine the management of these lesions, with long-term outcome data being collected for assessment of clinical efficacy.

Surgical Decision Making

Regardless of the classification system used, careful evaluation of the patient, including level of functional impairment, pain, concomitant pathology, expectations, and goals are essential in the decision-making process. The nature of injury, whether traumatic or from chronic overuse may also predict suitability for repair. Ultimately, the decision must be made whether labral damage is amenable to repair or more suitable for debridement. It is critical to identify the underlying cause(s) of labral damage and how best to address them, as well as to recognize associated damage (e.g., adjacent cartilage delamination) and integrate these factors into the decision-making process. The location of labral damage is important, as vascular supply is critical for healing and decreases toward the periphery. Labral tissue quality is also a factor in determining whether the repaired tissue is viable or more likely to undergo subsequent retearing. Systemic patholaxity (e.g., Ehlers–Danlos syndrome) versus local attenuation of tissue may be seen and should be taken into consideration.

Early efforts focused on labral debridement. In a case series 30 years ago, Harris et al. (17) found at the time of surgery that the acetabular labrum was found to lie in the articulation between the femoral head and the acetabulum in eight cases of idiopathic degenerative arthritis of the hip. They postulated that this inverted acetabular labrum was a developmental abnormality and the cause of degenerative arthritis. More recently, Seldes et al. (2) examined 67 cadaveric hips with a mean age of 78 years. In addition to characterizing tear patterns of the acetabular labrum, they noted that this was a highly prevalent finding in aging arthritic hips. Their conclusion was also that this might be one of the causes of degenerative hip disease.

Although it is now generally agreed that labral damage occurs as a result of degenerative changes, rather than being a cause of them, patients with symptomatic tears of the labrum in the setting of osteoarthritis may be considered for arthroscopic debridement, though the results are not as good

as labral debridement in nonarthritic hips. Using standard radiographs and CT scans of the hip, respectively, Wenger et al. (18 and Dolan et al. 19) concluded that labral tears rarely occurred in the absence of bony abnormalities. Commonly, patients with early symptoms of FAI present with labral damage as a result of bony impingement. Alternatively, patients with dysplasia may present with labral tears. Addressing these underlying causes of labral damage is essential in preventing recurrence and resolving symptoms. Efforts should also be made to preserve the function of the labrum in these cases, when possible.

as labral debridement in nonarthritic hips. Using standard radiographs and CT scans of the hip, respectively, Wenger et al. (18 and Dolan et al. 19) concluded that labral tears rarely occurred in the absence of bony abnormalities. Commonly, patients with early symptoms of FAI present with labral damage as a result of bony impingement. Alternatively, patients with dysplasia may present with labral tears. Addressing these underlying causes of labral damage is essential in preventing recurrence and resolving symptoms. Efforts should also be made to preserve the function of the labrum in these cases, when possible.

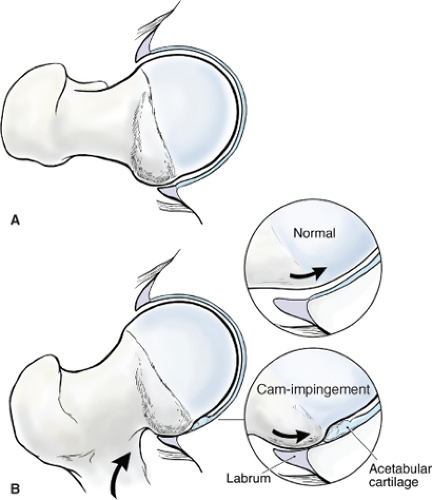

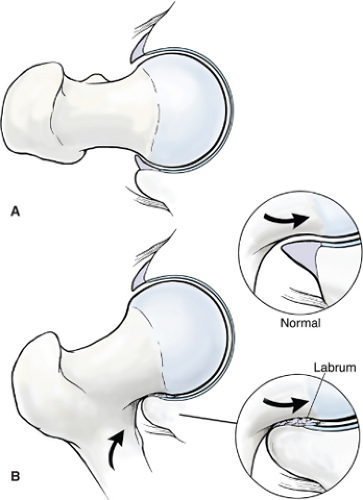

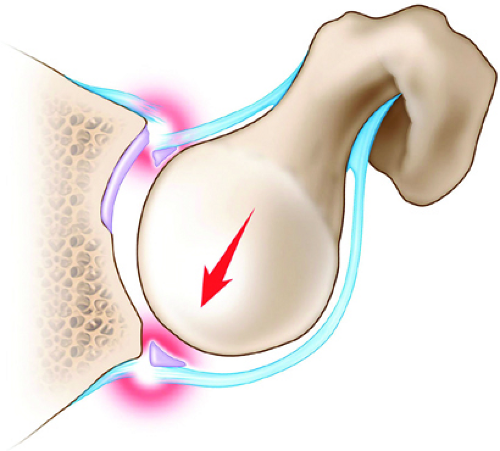

In general, FAI falls into three categories: cam-type, pincer-type, and mixed-type impingement. In cam-type impingement, bony overgrowth at the femoral head–neck junction typically initially results in lifting of the labrum and separation at the labral–chondral junction. As the cam defect approaches the acetabular rim, forces are directed under the labrum causing it to deflect outward (Fig. 46.5). Articular cartilage delamination or fissuring is common in this scenario and tend to be deep and localized to the anterosuperior acetabulum. Although the labrum is often detached or separated from the acetabular rim, the body remains intact with minimal deformation of the normal architecture in early stages of impingement. These tears can often be repaired after addressing the underlying bony deformity and concomitant cartilage lesions. In later stages of cam-type impingement, frank tearing of the labrum may occur, with complete separation from the chondral rim. Although these lesions may be repaired as well, disruption of the vascular supply as well as intrasubstance tearing may worsen outcomes. In the case of pincer-type impingement, excess coverage of the femoral head by a prominent acetabular rim results in labral damage that is typically intrasubstance. Here, as the pincer edge impacts against the femoral neck, the labrum is compressed and distortion of its gross morphology occurs. Although the labrum remains well attached to the acetabular rim, irreparable damage to the labrum often occurs, with fibrillation and attenuation of the longitudinal fibers (Fig. 46.6). The articular cartilage tends to have damage that is not as deep, but more global throughout the acetabular rim. This may include posterior acetabular damage with concomitant femoral head defects, as a result of a levering effect, described as a contrecoup injury (Fig. 46.7). These labral injuries are usually addressed with debridement, with the goal of limiting propagation of any tears and minimizing pain generators. If the labral substance has reasonable integrity, the labrum may be detached from the acetabular rim to perform acetabuloplasty with subsequent refixation to the new rim. Some surgeons will attempt to leave the labrum intact while performing an acetabuloplasty. However, since acetabular bone underlies the labrum, this may destabilize the labrum, requiring repair. It is the

preference of the senior author not to use this technique. Mixed-type impingement combines characteristics of each subtype (though damage caused by one type may predominate) and may require a combination of techniques to restore the function of the labrum. These changes may occur in different regions of the labrum (e.g., cam-type impingement anterosuperiorly with pincer-type impingement more posterosuperiorly). This is often reflected in the wear pattern seen in the adjacent cartilage.

preference of the senior author not to use this technique. Mixed-type impingement combines characteristics of each subtype (though damage caused by one type may predominate) and may require a combination of techniques to restore the function of the labrum. These changes may occur in different regions of the labrum (e.g., cam-type impingement anterosuperiorly with pincer-type impingement more posterosuperiorly). This is often reflected in the wear pattern seen in the adjacent cartilage.

Finally, in cases of irreparable damage to the labrum in an otherwise healthy joint, labral reconstruction has been described. Here, several different graft options have been used, including allograft as well as autograft iliotibial band (20), ligamentum teres capitis (21), gracilis (22), and rectus femoris (Thomas Sampson, MD, personal communication.). Each of these methods attempts to reconstitute the function of the labrum by substitution of exogenous tissue. Although seemingly effective in the short term, no long-term outcome studies have yet been reported. Moreover, there is a lack of data demonstrating the effectiveness of these techniques in restoring the function of the labrum.

Outcomes

Surgical management of labral pathology has only recently emerged as a discrete entity as our understanding of the role of the labrum has increased. Although increasing numbers of mid- and long-term data are being reported, many of the approaches toward management of labral pathology, including treatment of underlying bony defects, have changed in recent years. Many reports include heterogeneous patient populations, with etiologies as disparate as trauma, developmental dysplasia, arthritis, and FAI. Furthermore, as is often the case with new technology and procedures, the majority of studies continue to be level IV on the basis of evidence and data analysis is hampered by the use of outcome measures that were originally designed for use in patients undergoing hip arthroplasty. As advances in arthroscopic instrumentation and techniques have improved our ability to perform complex procedures within the hip joint, many of the early reports may not accurately represent the current state of labral surgery.

A recent meta-analysis of open treatment for FAI, including labral debridement or repair, documented good-to-excellent outcomes in 76% to 100% of patients (23).

Farjo et al. (24) reported the first comprehensive review of hip arthroscopy for labral tears in 1999. They found in 28 hips (mean age 41, duration of follow-up 34 months) that the only factor that correlated with outcomes was the presence of arthritis, whether seen radiographically or during arthroscopy as chondromalacia. Santori and Villar (25) reported shortly thereafter on 58 patients who underwent arthroscopic debridement for labral tears. They, on the basis of modified Harris Hip Scores at 3.5-year follow-up, found no correlation with concomitant chondral damage and had an overall 67% satisfaction rate. More recently, Byrd and Jones (26) reported 10-year data on arthroscopic labral debridement. Using modified Harris Hip Scores, they found that the greatest clinical correlate to poor outcomes was preexisting osteoarthritis. Patients without evidence of arthritis showed a median 39 point improvement at 3 months that was maintained throughout the duration of the study. Patients with AVN also faired poorly, although arthroscopy was undertaken as a palliative procedure in these cases.

Taken together, these data illustrate the difficulty in making definitive conclusions regarding debridement of labral tears. The inclusion of patients with underlying arthritis or other hip pathology clouds the clinical picture for those with isolated early-stage FAI. Moreover, the use of scoring systems designed originally for delineating outcomes in the setting of osteoarthritis may overlook functional outcomes relevant to younger active patients because of a ceiling effect. Finally, careful examination of the surgical indications for individual cases reveals extensive heterogeneity, from removal of loose bodies to synovectomy to debridement for chondromalacia and/or labral tears. Perhaps more important is the treatment of underlying pathology in the setting of labral tears. Bardakos et al. (27) compared outcomes from labral debridement in the context of cam-type FAI. At 1-year follow-up, patients who underwent labral debridement with concomitant cheilectomy (femoral osteoplasty) had higher outcome scores than patients who underwent labral debridement alone.

Labral repair is a more recent technique than debridement, with much less outcome data. In principle, given the important role of the labrum in preserving normal hip biomechanics, it would seem intuitive that repair of the labrum, when possible, would yield the best success in restoration of normal function. Tears at the labral–chondral junction would be expected to have higher rates of healing than more central tears because of the peripheral nature of the vascular supply.