4

Felons

Sam Moghtaderi and Kevin D. Plancher

History and Clinical Presentation

A 15-year-old, left-hand dominant boy with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus who monitors his blood glucose via multiple daily finger sticks presented to his physician complaining of extreme throbbing pain of his right middle fingertip for the past 24 hours.

Physical Examination

Examination of the affected finger demonstrated the volar aspect of the tip to be swollen, hard, and erythematous. The distal phalanx was extremely tender and somewhat fluctuant, but there was no pain in the distal interphalangeal joint or the more proximal regions of the finger. The dorsum of the phalanx, including the nail and periungual areas, appeared normal.

Diagnostic Studies

Anteroposterior and lateral plain film radiographs of the finger were obtained and demonstrated no abnormal findings.

PEARLS

- Often history of skin-penetrating injury

- “Throbbing pain” keeps patient from sleeping

- Conservative therapy effective for cellulitis—before the onset of pain

- Gram-negative coverage is essential in empiric antibiotic treatment of diabetics and immunocompromised patients

- Immobilization for first 48 hours, then active ROM exercises at dressing changes

PITFALLS

- Best routine incision is controversial

- In subcutaneous dissection, must avoid approaching the flexor tendon sheath

- Multitude of complications for neglected felon

Differential Diagnosis

Cellulitis

Flexor tenosynovitis

Herpetic whitlow

Metastatic tumor

Diagnosis

Felon of the Right Middle Finger

A felon is a bacterial infection of the distal pulp space of the fingers or thumb. As first described by Kanavel, the anatomy of the distal phalanx is unique, with the volar pulp space a confined sac, and fine fibrous septa connecting the subcutaneous layer to the bone (Fig. 4–1). An abscess in this region can lead to tensioning of the fibrous strands, increased pressure within the pulp space, and essentially a compartment syndrome with neurovascular compromise. In this way, a felon is distinguished from a simple superficial cellulitis, which may precede it. The patient with a felon presents with a swollen, hard, fluctuant, and erythematous fingertip, typically complaining of a throbbing pain so severe that it has kept him from sleeping.

There is usually a history of some penetrating trauma to the fingertip, which served as the inoculating event (splinter, broken glass, etc.), although it may have been rather inconsequential and forgotten by the patient. It is also possible that the organisms entered in retrograde fashion via the eccrine or sebaceous glands in the finger pad. Although diabetics and immunocompromised patients are generally at higher risk for hand infections, those who require routine blood monitoring via finger sticks have an additional risk for inoculating so-called finger stick felons. Skin flora comprises the organisms commonly seen in felons, and most often it is Staphylococcus aureus or other gram-positive organisms.

Figure 4–1. Schematic anatomic drawing of digital pulp sac.

It is important to distinguish herpes infections of the fingertip from bacterial felons. Herpetic whitlow is a self-limited viral infection caused by the herpes simplex virus. It is transmitted by skin-to-skin contact, and is often seen in medical and dental personnel, as well as in children. The course of the presentation of a herpes lesion is much longer than that of a felon, which is typically quite acute. Herpetic whitlow may present with swelling and erythema, but typically displays fluid-filled vesicles as well. The diagnosis is usually made clinically, although it is possible to confirm it by use of a Tzanck prep or viral culture. It is important to distinguish herpetic whitlow from bacterial infections, as a surgical incision for the former can lead to complications involving the entire digit or systemic spread, and is contraindicated.

Nonsurgical Management

Infection of the pad of the finger can be managed nonoperatively if the superficial cellulitis, as is typically the case during the first 48 hours, has not spread. In such instances, elevation, warm soaks, and a course of oral antibiotics (typically dicloxacillin or a first-generation cephalosporin to cover gram-positives and skin flora) suffice. In the case of a diabetic or immunocompromised patient, however, additional gram-negative coverage is essential.

Surgical incision is indicated as soon as the patient’s pain and physical exam indicate increased pressures in the pulp space, despite the absence of fluctuant abscess.

Surgical Management

A felon requires surgical drainage both to clear the infection and to relieve the intracompartmental pressure and prevent neurovascular compromise. All of the procedures outlined here are typically done using local anesthesia and under tourniquet control. There is little disagreement over when surgical management is indicated. There is, however, controversy over the most appropriate surgical approach for routine incision and drainage of felons. The goal, similar in all techniques, is to adequately drain the abscess while minimizing damage to neurovascular structures and scar formation in critical areas.

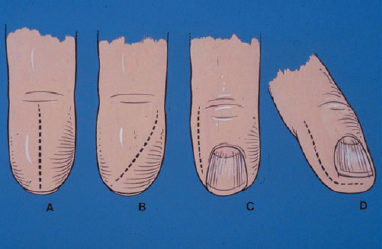

Most surgeons use a unilateral longitudinal approach, where an incision is made on the unopposing lateral side of the digit (ulnar for the fingers and radial for the thumb), beginning just dorsal to and 5 mm distal to the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint flexion crease and continuing lateral to the nail edge to a point just distal to the unattached portion of the nail (Fig. 4–2). The incision is deepened by blunt dissection with a hemostat or similar instrument, until the abscess is adequately opened for draining. Extreme care must be taken so as not to dissect in a proximal direction, to reduce the likelihood of piercing the flexor tendon sheath and causing an iatrogenic tenosynovitis.

An alternative approach, suggested by Kilgore for routine drainage of all felons, is the longitudinal volar incision. He contends that scar formation is minimal, and that there is actually more likelihood of neurovascular damage when the lateral approach is used. Most authors, however, prefer the lateral approach, citing concerns about scar formation over the most important tactile region of the fingertip. Volar incisions are typically used only when the abscess is smaller and localizable to the volar pad, or when a sinus tract already exists. The longitudinal volar incision is made in the midline extending from the tip of the pad to within several millimeters of the DIP joint flexion crease proximally. It is important not to cross the flexion crease, as a subsequent scar will then lead to a flexion contracture. Alternatively, the volar incision can be made transversely over the point where the abscess is best localized. In either case, once the skin incision is made, blunt subcutaneous dissection is performed as above, taking care not to dissect too far proximally to endanger the tendon sheath.