Extra-articular Snapping Hip Syndromes

Victor M. Ilizaliturri Jr

Francisco C. Lopez

Introduction

Indications for endoscopic surgery of the hip have expanded recently. The technique has found a clear role in the management of extra-articular snapping hip syndromes. Traditionally three different types of snapping hips have been described; external, internal, and intra-articular (1). The term intra-articular snapping hip referred to intra-articular situations that produced mechanical hip symptoms such as catching, locking, and giving away and that could also be interpreted as a snapping-like phenomenon. Loose bodies, labral or ligamentum teres tears were described as etiologies for the so-called intra-articular snapping hip (1). Because today we are more specific when determining intra-articular pathology, the term intra-articular snapping hip is in disuse (2,3). Even though the external and internal snapping hips share a common name, they are very different in origin. The first type of snapping hip syndrome that was recognized is the external snapping hip syndrome (4). It is produced by the iliotibial band (ITB) sliding over the greater trochanter with flexion and extension of the hip. The internal snapping hip syndrome, which was first reported in Argentina (5), is produced by the iliopsoas tendon snapping over the iliopectineal eminence or the femoral head. Because the internal and external snapping hip syndromes are so different in origin, the history, physical examination findings, diagnostic studies, and treatment are also very different.

External Snapping Hip Syndrome

The external snapping hip syndrome is produced by a posterior thickening of the ITB and thickening of the anterior fibers of the gluteus maximus. These fibers lie posterior to the greater trochanter. The thickened fibers snap over the greater trochanter with flexion and extension of the hip and in more severe cases the phenomenon may also be reproduced with hip rotations (1).

Clinical Presentation

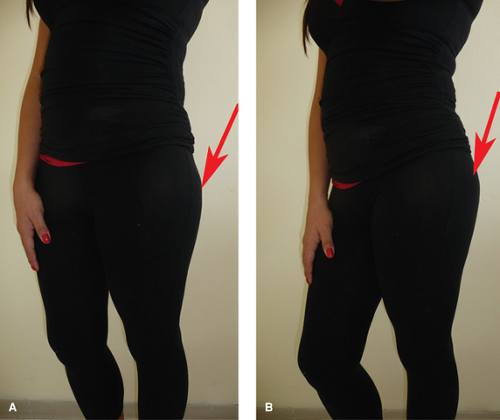

This phenomenon is always voluntary and the patient often volunteers to demonstrate it (1). Asymptomatic snapping must always be considered a normal occurrence (6). Diagnosis is evident; the snapping will occur when flexing and extending the hip (we prefer to examine this with the patient in lateral decubitus by passively flexing and extending the hip) (Fig. 31.1). In some cases the snapping phenomenon may be visible under the skin and in some other cases it may be palpated over the area of the greater trochanter by placing the full extended palm over the area (Fig. 31.2). A different form of external snapping hip is also described by some patients as the ability to “dislocate the hip.” This is often demonstrated by rotating the affected hip while tilting the pelvis in a standing position (Fig. 31.3). The voluntary “dislocators” are more frequently painless and should only be treated with stretching exercises of the ITB. Symptomatic external snapping hip syndrome is always accompanied with pain in the greater trochanteric region (Fig. 31.4). The pain is secondary to greater trochanteric bursitis, inflammation of the ITB itself, or abductor tendon pathology. A positive Ober test (6) may also be found at physical examination (Fig. 31.5). When Trendelenburg gait is also found, an associated abductor muscle tear must be suspected, this is an indication for surgical treatment. Trendelenburg may not be initially apparent, but may become positive if a fatigue Trendelenburg test is performed. This consists of asking the patient to perform a single leg stance over periods of 10 seconds with a 10-second increment in each period; if there is abductor pathology the sign becomes positive within 20 seconds. The test is carried out comparatively (Fig. 31.6) (7).

Imaging of the External Snapping Hip

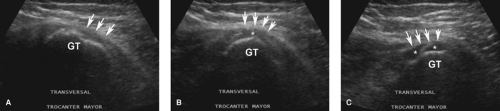

Anteroposterior pelvis x-rays should always be done to identify bony abnormalities, calcifications, or other pathology. The snapping phenomenon can be documented with dynamic ultrasonography and this examination can detect associated pathology such as tendonitis, bursitis, or muscle tears (Fig. 31.7) (7,8,9). Iliopsoas bursitis and abductor muscle tears can be diagnosed using magnetic resonance imaging (10,11).

Conservative Treatment

Most of the symptomatic cases improve with stretching physical therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory therapy,

and corticosteroid infiltration of the greater trochanter bursa (1). The physical therapy protocol is established for 2 months, when the protocol is completed the patient is re-evaluated, if no improvement is obtained surgical treatment is discussed. A maximum of three corticosteroid injections are used in the area of the trochanteric bursa and rest from physical therapy is always indicated for 3 days after the injection. When conservative treatment fails, surgical release is indicated. Open ITB release or lengthening has been the traditional surgical option to treat the external snapping hip syndrome (12,13,14,15,16). Recently, we have described a technique for endoscopic ITB release for the treatment of external snapping hip syndrome (17).

and corticosteroid infiltration of the greater trochanter bursa (1). The physical therapy protocol is established for 2 months, when the protocol is completed the patient is re-evaluated, if no improvement is obtained surgical treatment is discussed. A maximum of three corticosteroid injections are used in the area of the trochanteric bursa and rest from physical therapy is always indicated for 3 days after the injection. When conservative treatment fails, surgical release is indicated. Open ITB release or lengthening has been the traditional surgical option to treat the external snapping hip syndrome (12,13,14,15,16). Recently, we have described a technique for endoscopic ITB release for the treatment of external snapping hip syndrome (17).

Figure 31.2. The snapping phenomenon is reproduced as presented in Figure 31.1. In this case the full extended palm is over the area of the greater trochanter to detect the snapping. A: Extension. B: Flexion. |

Endoscopic Release of the Iliotibial Band

Our protocol for endoscopic release of the ITB for the treatment of external snapping hip syndrome is presented (17):

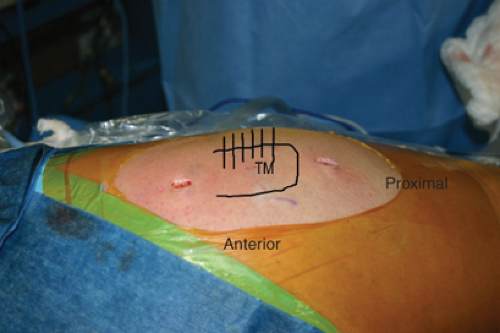

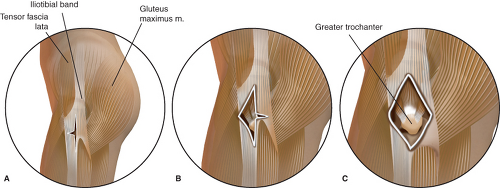

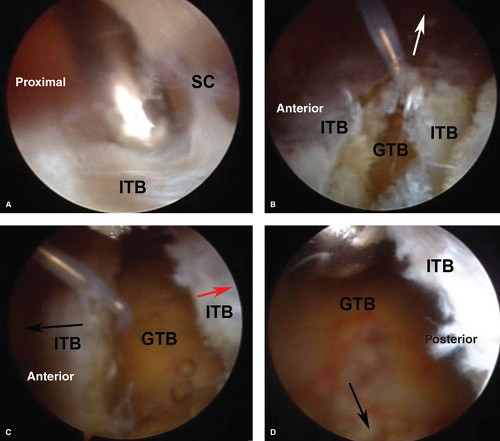

We position the patient lateral similar to the setup for total hip replacement. Surgical drapes must allow for free range of motion of the lower extremity to reproduce the snapping phenomenon during surgery. No traction is necessary to access the greater trochanteric bursa and the ITB. The greater trochanter is the main landmark for portal placement and is marked on the skin using a skin marker. We utilize two portals, a proximal trochanteric and distal trochanteric (Fig. 31.8). The area of snapping should be between both portals to ensure ITB release will include the area that generates the problem. We also mark the area of snapping on the skin. We start by infiltrating the space under the ITB with 40 to 50 cc of saline. Next the inferior trochanteric portal is established using a standard arthroscopic cannula that is introduced under the skin and directed proximally to the site of the superior trochanteric portal using the blunt obturator to develop a working space above the ITB. The site of the proximal trochanteric portal is identified arthroscopically using a needle inserted at the portal landmark, the skin incision is made and a shaver is introduced to dissect subcutaneous tissue from the ITB situated between the portals. Hemostasis is performed in this step to allow clear visualization of the ITB. Then a radiofrequency hook probe is introduced from the proximal trochanteric portal and a 4- to 6-cm vertical retrograde cut is performed on the ITB starting at the level of the inferior trochanteric portal. The pump pressure should be kept low while working on the subcutaneous space to avoid complications with the skin. Once the vertical cut on the ITB is complete the pump pressure can be increased and a transverse anterior cut of 2 cm in length is performed starting at the middle of the vertical cut. The resulting superior and inferior anterior flaps are resected using a shaver developing a triangular defect on the anterior ITB that will provide access to the posterior ITB. Next a transverse posterior cut is started at the same level of the transverse anterior cut. This is the most important release and should be carried out until the snapping phenomenon is solved. Finally the superior and inferior posterior flaps are resected, which results in a diamond-shaped defect on the ITB. The greater trochanter will rotate freely within the defect with out snapping. The greater trochanteric bursa should be removed through the defect on the ITB and the abductor tendons inspected for tears (Figs. 31.9 and 31.10).

We position the patient lateral similar to the setup for total hip replacement. Surgical drapes must allow for free range of motion of the lower extremity to reproduce the snapping phenomenon during surgery. No traction is necessary to access the greater trochanteric bursa and the ITB. The greater trochanter is the main landmark for portal placement and is marked on the skin using a skin marker. We utilize two portals, a proximal trochanteric and distal trochanteric (Fig. 31.8). The area of snapping should be between both portals to ensure ITB release will include the area that generates the problem. We also mark the area of snapping on the skin. We start by infiltrating the space under the ITB with 40 to 50 cc of saline. Next the inferior trochanteric portal is established using a standard arthroscopic cannula that is introduced under the skin and directed proximally to the site of the superior trochanteric portal using the blunt obturator to develop a working space above the ITB. The site of the proximal trochanteric portal is identified arthroscopically using a needle inserted at the portal landmark, the skin incision is made and a shaver is introduced to dissect subcutaneous tissue from the ITB situated between the portals. Hemostasis is performed in this step to allow clear visualization of the ITB. Then a radiofrequency hook probe is introduced from the proximal trochanteric portal and a 4- to 6-cm vertical retrograde cut is performed on the ITB starting at the level of the inferior trochanteric portal. The pump pressure should be kept low while working on the subcutaneous space to avoid complications with the skin. Once the vertical cut on the ITB is complete the pump pressure can be increased and a transverse anterior cut of 2 cm in length is performed starting at the middle of the vertical cut. The resulting superior and inferior anterior flaps are resected using a shaver developing a triangular defect on the anterior ITB that will provide access to the posterior ITB. Next a transverse posterior cut is started at the same level of the transverse anterior cut. This is the most important release and should be carried out until the snapping phenomenon is solved. Finally the superior and inferior posterior flaps are resected, which results in a diamond-shaped defect on the ITB. The greater trochanter will rotate freely within the defect with out snapping. The greater trochanteric bursa should be removed through the defect on the ITB and the abductor tendons inspected for tears (Figs. 31.9 and 31.10).

When hip arthroscopy is also necessary we start with the patient positioned lateral for hip arthroscopy, we perform arthroscopy of the central and peripheral compartments of the hip. After hip arthroscopy is complete, the foot is released from the traction device and the endoscopic ITB release performed as described.

An alternative technique has been presented by Voos et al. (18), consisting of accessing the peritrochanteric space (between the ITB and the greater trochanter) and releasing the ITB under direct arthroscopic vision from inside the thigh compartment. No results are reported in this technical note.

Results

Published literature on the results of surgical treatment of the external snapping hip syndrome is limited. Most of the literature reports on open releases of the ITB (12,13,14,15,16) and the evidence is anecdotal. Recently we reported the results of an endoscopic technique to release the ITB with greater trochanteric bursectomy and examination of the abductor tendons (17). A summary of the results of open and endoscopic techniques for ITB release in the treatment of external snapping hip syndrome is presented in Table 31.1. There is very little information on the results of the endoscopic technique, as shown in Table 31.1, these results compare well with the reported results of open surgical procedures.

Table 31.1 Results of Iliotibial Band Release | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

There have been no complications reported with this technique other than the persistence of the snapping phenomenon, which can be considered failure of the treatment. More studies and follow-up are needed to identify and describe possible complications. The situation of the sciatic nerve in close proximity to the posterior margin of the greater trochanter may be of concern when surgery of the peritrochanteric space is performed. No complications regarding injury to the sciatic nerve have been reported.