Fig. 3.1

The interplay between the extrinsic and intrinsic tendons creates a “tenodesis effect.” Extension of the wrist will cause the fingers to flex (a), and flexion of the wrist will cause the fingers to extend (b). Note the normal “cascade” of fingers in the lax position

Fig. 3.2

A small cut on the volar aspect of the middle finger resulted in a laceration of the flexor tendons to this finger. The result is the deviation of the middle finger from its normal position in the finger “cascade”

Flexion of the wrist will cause the normal digits to extend. This is termed the tenodesis effect and is related to the interplay between the flexor, extensor, and intrinsic tendons (Fig. 3.1a, b). It is an important sign for evaluating passive extension when the patient is not cooperative (as with a child) or under anesthesia. This effect may also accentuate a deviation of one of the digits from the normal cascade of fingers.

Snapping of a joint may be revealed with active flexion and extension of the fingers. Commonly, this may be unrelated and due to stenosing flexor tenosynovitis (“trigger finger”), although it may be related to snapping of an extensor tendon following rupture of a sagittal band (related to repetitive direct trauma to the knuckle) [1]. With careful examination, subluxation of the tendon off the head of the metacarpus may be seen.

Further evaluation will be directed according to the mechanism of injury and the observed injury characteristics. Blunt injuries should be the examined focusing on the bone and joint function. With simple penetrating injuries, the tendon function and nerve dysfunction will be the focus of the examination. A penetrating injury should be evaluated while keeping in mind the structures in the zone of injury – tendons, nerves, arteries, and joints. Knowledge of the anatomy is of special importance in these cases, examining specific structures known to cross the zone of injury.

Evaluate the entire upper extremity as well as the cervical spine for additional injuries or referred pain from other locations, and consider neuropathic pain. For example, cubital tunnel syndrome may cause pain in a previously injured small finger, as part of its manifestation. Differential diagnosis is crucial.

3.2.2 Skeletal Trauma

The osseous anatomy of the metacarpals and phalanges is easy to palpate, and bony injury may be readily diagnosed. Most hand fractures related to athletic trauma are stable due to lower energy of injury [1]. This will result in swelling and pain and less deformity and commonly bring the patient for evaluation only late in the course of healing. A stress fracture should be considered when the patient presents with progressive localized mechanical pain with induration [5].

3.2.3 Articular Injury

The most common sport-related joint injuries in the hand involve the PIP joint of the digits, MP joint of the thumb, and basilar joint of the thumb [1]. Localized symptoms over a joint should be assessed for each joint specifically. In chronic injuries, persistent pain, subjective alteration in hand function, and a sense of instability may be part of the complaints. Commonly, signs of degenerative changes of the joint will already be present [2].

Carefully palpate and elicit localized tenderness over the painful or swollen joint to assess the location of injury of the joint – each collateral ligament, the volar plate, or the dorsal joint. Dorsally, tendinous avulsions (e.g., central slip or terminal tendon of the extensor apparatus) may result in deformity as well as localized tenderness. In the case of the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) of the metacarpophalangeal (MP) joint or Stener lesion, a mass may be palpated on the ulnar side of the joint at the location of the avulsed ligament.

Assess joint stability, taking into account the location of pain and tenderness. This is of special importance with suspected collateral ligament injuries. An intra-articular grinding sensation with manipulation of the joint may be a sign of intra-articular involvement of a fracture or degenerative changes of the joint.

The evaluation of joint stability is vital in situations such as the UCL of the thumb MP joint where differentiation between complete tears and partial tears should be made. Evaluation of stability under local anesthesia and fluoroscopy may aid in this case. Stressing the joint in radial and ulnar directions should be performed in extension and flexion, while comparing the sense of a firm “end point” to the contralateral side joint (Table 3.1). Some recommend evaluation of the stability of the UCL of the thumb MPJ in flexion of 40° where the ligament was found to be most taught [6, 7] (Fig. 3.3). Extension will rule out injury to the volar plate [7].

Table 3.1

Joint laxity grading

Grade 1 | Tenderness to palpation over the collateral ligament but no measured laxity compared with the contralateral digit |

Grade 2 | Laxity greater than the contralateral digit but with a definite, firm endpoint |

Grade 3 | No discernable end point to applied stress |

Fig. 3.3

The thumb metacarpophalangeal joint stability is examined at an angle of 40°. To evaluate the integrity of the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL), pressure is placed on the radial neck of the metacarpal and the base of the proximal phalanx, in an attempt to gap open the joint. Startle of the patient or localized ulnar pain with this manipulation may indicate a partial tear of the UCL, while a complete tear will be sensed by the lack of a clear endpoint

More severe injuries will result in an irreducible position of the joint where soft-tissue interposition is present or in dynamic instability where simply flexing or extending the digit (under local anesthesia) results in subluxation of the joint [7]. Acutely, these injuries will present with more significant swelling or deformity.

For the PIP joint, the ultimate determinant of treatment is whether the joint remains concentrically reduced with active motion. Under local anesthesia, the stability may be evaluated actively and redisplacement with motion indicates significant ligament disruption.

A “jersey finger” is the eponym for the traumatic avulsion of the flexor digitorum profundus muscle at its insertion. Dysfunction of the tendon as well as localized volar swelling and tenderness over the volar distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint will be present.

In chronic PIP joint hyperextension injuries, the examiner must distinguish primary volar plate laxity from an extensor mechanism imbalance, developing secondary to a severe mallet finger injury. The distinction can be made by stabilizing the PIP joint in full extension as the patient attempts active extension of the distal joint. Significant lag in active distal extension with the PIP joint stabilized in neutral is primarily a problem of the extensor mechanism. If the distal joint extends normally, the problem is with the volar plate of the PIP joint [7].

3.2.4 Range of Motion

3.2.4.1 Finger Range of Motion

Passive versus active range of motion should be evaluated and documented during the initial assessment to enable evaluation of progression in follow-up examinations. Finger motion can be measured in terms of the difference between the degrees of maximal extension to the degrees of maximal flexion. Hyperextension is recorded as a negative number. The interphalangeal (IP) joints of the fingers have mainly flexion and extension with very limited rotation, hyperextension, or deviation. The MP joint is more flexible. The total joint motion of the MP joint as well as the finger is the sum of flexion and the negative sum of hyperextension. Abduction and adduction of the fingers occurs mainly at the MP joints in extension when the collateral ligaments are more lax. There is some motion in the finger carpometacarpal (CMC) joints, approximately 10–15° in the ring and small fingers and a few degrees in the index and middle fingers. This is best demonstrated by asking the patient to make a relaxed fist and then clench the fist with more effort, marking the flexion of the small and ring finger CMC joints. There is some rotation possible, especially in the small finger CMC joint resulting in the ability to cup the hand.

3.2.4.2 Thumb Range of Motion

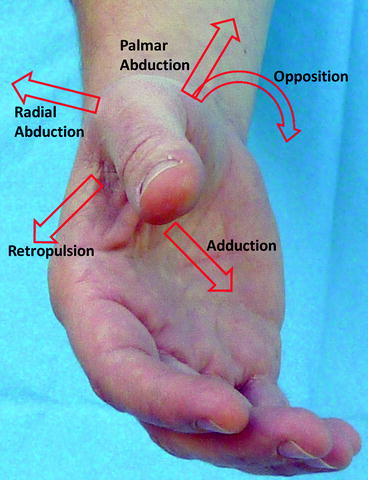

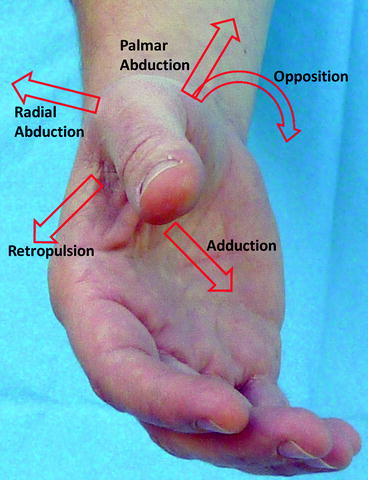

The thumb motion is recorded as flexion and hyperextension with the total motion equaling flexion minus hyperextension. The thumb motion also includes palmar and radial abduction, opposition, and retroposition. The IP joint and MP joint of the thumb mainly flex and extend. The normal range of motion of the MPJ is highly variable. The majority of rotation and abduction of the thumb is achieved at the trapezometacarpal joint.

It is difficult to obtain angular measurements for opposition and abduction of the thumb [9]. Opposition can be evaluated when the thumb is brought from the position of adduction directly over the third metacarpal as the absolute number of centimeters of distance from the flexion crease of the thumb interphalangeal joint to the distal palmar crease. Thumb abduction can be measured as the absolute distance from the thumb IP joint flexion crease to the distal palmar crease at the base of the small finger. This may be performed either for palmar or radial abduction (Fig. 3.4).

Fig. 3.4

Range of motion of the thumb carpometacarpal joint

3.2.5 Evaluation of Tendon Integrity and Function

The extrinsic extensor tendons are contained in six dorsal compartments at the wrist and should be evaluated systematically (Table 3.2).

Table 3.2

Examination of the extrinsic extensor tendons by their compartments

Compartment | Muscles evaluated | Ask patient to |

|---|---|---|

1 | Extensor pollicis brevis (EPB) and abductor pollicis longus (APL) | Bring the thumb away from the index finger (radially abduct), while palpating the taut tendonsa (Fig. 3.5) |

2 | Extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) and longus (ECRL) | Extend and radially deviate the wrist with the hand in a fist position while palpating the taut tendons on the dorsal-radial side of the wrist (Fig. 3.6) |

3 | Extensor pollicis longus (EPL) | Place the hand flat on a table and lift only the thumb off the table (Fig. 3.7) |

4 | Extensor digitorum communis (EDC) and extensor indicis proprius (EIP) | Straighten the fingers while observing MP joint extension. The EIP can be isolated by asking the patient to extend the index finger with the other digits flexed (Figs. 3.8 and 3.9)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|