Evaluation and Treatment of Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis in Skeletally Immature Patients

Daniel J. Sucato

Adriana De La Rocha

Overview

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) is one of the most common hip conditions in children. In SCFE, the femoral neck and shaft become displaced anteriorly relative to the epiphysis and as the slip progresses, an increasing posterior angulation between the epiphysis and the remainder of the femur occurs (Fig. 48.1) (1). The goal of evaluation and treatment in the skeletally immature patient is to optimize epiphyseal position minimizing deformity and femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) which can lead to early osteoarthritis in later adolescence or adulthood (2,3). The development of avascular necrosis (AVN) is initially related to physeal stability and later to timing of surgery and the surgical approach. A better understanding of the development of AVN and methods to prevent it will be important to improve the overall outcome of these patients.

Epidemiology and Etiology

The incidence of SCFE is approximately 2 per 100,000 cases in the general population (4). It is more common in boys than girls and affects African American children 3 times and Hispanic children 2.5 times more than White children (4). It has also been strongly associated with childhood obesity (5,6,7). In a recent study, hip motion and incidence of SCFE in a consecutive series of 411 patients at a mean age of 14.5 years (range: 7.8 to 20.4 years) and a mean BMI of 32.9 ± 5.6 kg/m (2) who were admitted for an inpatient weight loss program demonstrated that 26% of patients had load-dependent and 11.7% had load-independent pain in the knee joint and 9.3% and 4.7% in the hip joint, respectively. A total of 18.2% of the patients showed a reduced range of motion for hip flexion and a similar percentage had a significantly decreased internal rotation (8). The authors also reported that an abnormal head–neck ratio as a sign of a prior silent SCFE was present in 20% of a specific cohort of patients (8). The primary care physician and emergency room physician should be aware of the prevalence of SCFE in the young overweight or obese child with thigh or knee pain and obtain appropriate radiographic images to determine whether the diagnosis is present.

Patients with a higher BMI also have a higher likelihood of developing bilateral SCFEs (9,10,11). Bhatia et al. (9) found greater BMI in patients with bilateral disease than patients with unilateral disease. Further, patients with unilateral involvement who progressed to bilateral disease had a significantly greater average BMI than patients who did not progress (9). Another study of 502 patients treated for SCFE, 27% of which were bilateral found that gender, age, slip stability, and slip angle were not associated with

bilateral SCFE; however, postoperative obesity and acute slip chronicity had higher risks for sequential bilateral SCFEs (11). Physical activity, however, was not a risk factor for developing SCFE (12).

bilateral SCFE; however, postoperative obesity and acute slip chronicity had higher risks for sequential bilateral SCFEs (11). Physical activity, however, was not a risk factor for developing SCFE (12).

The exact cause of SCFE is unknown, although several endocrine, mechanical, and genetic factors have been proposed (13). SCFE may be associated with various underlying syndromes or conditions including renal failure and endocrine disorders and it is imperative to accurately diagnose and differentiate these patients from patients with idiopathic SCFE to prevent potential complications during treatment or surgery (Fig. 48.2) (14). Patients who present with SCFE that is secondary to another underlying condition are usually those younger than 10 years of age or older than 16 years of age and are 4.2 times more likely to have an atypical SCFE; for patients of equal age, those less than 50th percentile weight are 8.4 times more likely to have a secondary underlying diagnosis (15). The age–weight test is defined as negative when age is younger than 16 years and weight is greater than or equal to 50th percentile and positive when beyond these boundaries. The probability of a child with negative test results having an idiopathic SCFE was 93% and the probability of a child with a positive test result having an atypical SCFE was 52% (15). An evaluation of the child’s age and weight is useful when considering the cause of a SCFE (15). Adolescents with renal osteodystrophy may also be at risk for metaphyseal bone collapse which may mimic SCFE (Fig. 48.3). When children with renal insufficiency present with displacement of the capital femoral epiphysis, it is necessary to evaluate the serum levels of alkaline phosphatase and metaphyseal bone quality below the physis (16).

Genetic evaluation of the tissues of patients with SCFE has also enabled detailed analysis of the expression of proteins for key structural molecules in growth plate chondrocytes. Scharschmidt et al. (17) completed a core biopsy of the proximal femoral physis in nine patients with SCFE and the specimens were compared with five specimens from the normal distal femoral and proximal tibial and fibular physes of age-matched patients treated surgically for limb-length inequality. The authors found that downregulation of both type-II collagen and aggrecan was found in the growth plates of the subjects with SCFE when compared with levels in the age-matched controls (17).

Classification

An older classification for SCFE utilized duration of symptoms prior to presentation to best categorize patients and included acute (symptoms persisted less than 3 weeks), chronic (symptoms persisted more than 3 weeks), and acute on chronic (acute exacerbation of long-standing symptoms) SCFEs. In recent years, physeal stability has become the most important consideration when classifying a SCFE since it predicts the most feared complication of AVN (18,19). Patients with a stable SCFE are mobile on their own with or without crutches but without the assistance of others whereas patients with an unstable SCFE, are not able to bear any weight 18 and require assistance to be mobile. Generally, stable SCFEs are more common than unstable slips. An unstable SCFE usually occurs as the result of an acute traumatic event such as a fall. Immediate and accurate evaluation of the type of SCFE is important for adequate treatment, as stable SCFEs have a significantly better prognosis with virtually no likelihood of developing AVN whereas unstable SCFEs have a very high incidence of developing AVN reported to be 47% in the paper of Loder et al. (18). A recent study reported differences in presentation with regard to complaints of pain and duration of symptoms between patients with stable and unstable SCFEs. The authors reviewed the records of 82 patients (41 males, 41 females) who presented with an unstable SCFE and found that a total of 88% of patients had pain in their hips, thighs,

or knees for an average of 42 days before sustaining unstable SCFEs with equal gender distribution (20).

or knees for an average of 42 days before sustaining unstable SCFEs with equal gender distribution (20).

Clinical Presentation and Evaluation

The complete evaluation of SCFE involves a careful review of the patient’s clinical symptoms in combination with various radiographic findings. Patients with a stable SCFE usually present with complaints of dull pain in the hip, thigh, or knee area that is exacerbated with strenuous activities and parents notice an intermittent limp. The localization of this pain may not be specific and primary care physicians and orthopedists must pay particular attention to pain that radiates to the lower extremity, especially the anterior aspect of the knee and distal thigh which often leads to a misdiagnosis (21). Studies have documented that approximately 50% of primary care visits for hip, groin, knee, or thigh pain in obese children did not lead to either a diagnosis of SCFE or a referral for orthopedic evaluation (22). Immediate and accurate diagnosis is imperative because a stable SCFE may become an unstable one which has a significantly higher risk of developing AVN and postoperative complications (Fig. 48.4) (21). Although SCFE severity generally increases with longer duration of symptoms, some patients have prolonged symptoms with mild SCFE whereas others have short symptoms with a severe SCFE (23).

The patient with a stable SCFE is able to bear weight, may walk with an antalgic gait but more commonly walks with a mild Trendelenburg lurch with some external rotation of the foot. The most important and classic physical examination findings include obligate external rotation of the hip during 90 degrees of hip flexion and limited internal rotation which often is associated with pain. Other range of motion including adduction, extension, and flexion will also be limited. Patients with an unstable SCFE have a far different presentation usually presenting with a clear history of a traumatic event, acute onset of severe, sharp pain in the groin region and have a presentation that is similar to an acute hip fracture. The patient will not be able to bear weight and the affected joint will be resting in external rotation and be too sensitive to allow for any passive range of motion without exacerbating the pain (a positive log roll test).

Imaging Evaluation

Radiographs

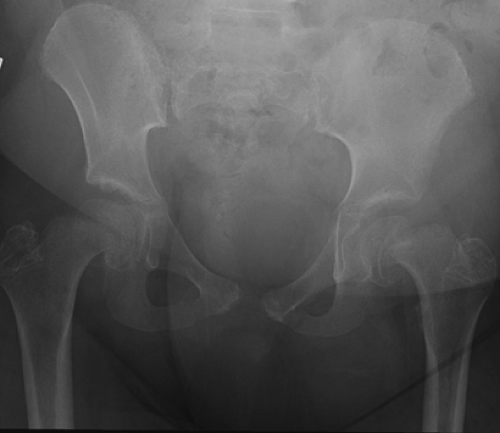

Patients who present with clinical symptoms of SCFE should be evaluated with an anteroposterior (AP) pelvis radiograph and a frog-leg pelvic radiograph so that first both hips are evaluated and second a view of the hip from the front as well as from the side is obtained. Authors have described various characteristics of SCFE that are easily identified on the AP radiograph which are useful in confirming the diagnosis including widening of the metaphysis and lack of intersection of the epiphysis with a line along the superolateral aspect of the femoral neck (Klein sign) (Fig. 48.5). In mild SCFE cases, however, application of the Klein’s line principle may be difficult and inaccurate and in some instances miss identification of up to 60% of slips. Recently, a modification to the Klein’s line principle was suggested that increased the sensitivity for identifying a SCFE on an AP radiograph in which the width of the epiphysis lateral to Klein’s line was measured (24). This improved the sensitivity to 79% if a

difference of 2 mm between the hips indicated a SCFE (24). The Steel sign has also been described and positive when a double density is found at the metaphysis which is caused by the posterior slip of the epiphysis being superimposed on the metaphysis. Other authors have also observed decreased epiphyseal height compared to the uninvolved side. In acute SCFE, there is also partly patchy, partly cystic changes in the metaphyseal part of the femoral neck (25). Recently, the acetabulotrochanteric distance has also been described as reliable radiographic parameter to delineate unilateral SCFE on the AP radiograph. Song et al. (26) reviewed 25 consecutive cases of unilateral SCFE and measured the acetabulotrochanteric distance (ATD) as the distance between a line connecting the first superolateral margins of the acetabulae with a second line, parallel to the first line, which goes through the tip of the greater trochanter on each hip. They also measured the acetabulotrochanteric angle (ATA) as the angle between a line connecting the superolateral margins of the acetabulum with a second line connecting the tip of the greater trochanter (26). They evaluated the difference in ATD and ATA and reported that 76% of cases demonstrated a difference in ATD of >2 mm and positive ATA divergence of >1 degree. The average difference in ATD was 6.6 mm and the average ATA divergence was 2.4 degrees (26).

difference of 2 mm between the hips indicated a SCFE (24). The Steel sign has also been described and positive when a double density is found at the metaphysis which is caused by the posterior slip of the epiphysis being superimposed on the metaphysis. Other authors have also observed decreased epiphyseal height compared to the uninvolved side. In acute SCFE, there is also partly patchy, partly cystic changes in the metaphyseal part of the femoral neck (25). Recently, the acetabulotrochanteric distance has also been described as reliable radiographic parameter to delineate unilateral SCFE on the AP radiograph. Song et al. (26) reviewed 25 consecutive cases of unilateral SCFE and measured the acetabulotrochanteric distance (ATD) as the distance between a line connecting the first superolateral margins of the acetabulae with a second line, parallel to the first line, which goes through the tip of the greater trochanter on each hip. They also measured the acetabulotrochanteric angle (ATA) as the angle between a line connecting the superolateral margins of the acetabulum with a second line connecting the tip of the greater trochanter (26). They evaluated the difference in ATD and ATA and reported that 76% of cases demonstrated a difference in ATD of >2 mm and positive ATA divergence of >1 degree. The average difference in ATD was 6.6 mm and the average ATA divergence was 2.4 degrees (26).

A lateral x-ray is also an essential view to obtain during the evaluation of a patient with a suspected SCFE because of the inferior, medial, and posterior nature of the slip (Fig. 48.6). Several lateral x-rays are available; however the frog-leg view is the most popular. It is obtained by having the patient flex and abduct the hips. This allows for the easy visualization of the bony anatomy of both hips and the soft tissue obscuring is minimized. Other lateral radiographs include the cross-table lateral x-ray, the modified Dunn lateral x-ray, and the Billing lateral x-rays. The importance of a concomitant lateral x-ray to supplement the AP x-ray has been thoroughly described by various authors, all of whom agree that the lateral image may help to identify subtle or less severe cases of SCFE which may be missed on the AP film in unilateral and bilateral involvement. The method described by Southwick in which the epiphyseal-shaft angle on the frog-leg lateral radiograph is also useful in quantifying and classifying the severity of the slip. The angle is calculated by subtracting the epiphyseal-shaft angle on the uninvolved side from that of the affected side. A mild slip is less than 30 degrees, a moderate slip is between 30 and 50 degrees, and a severe slip is greater than 50 degrees (27). Care should be taken, however, when using plain radiographs as a source to determine the severity of the slip in patients with SCFE as the reliability in the measurements may be low and the variability may be high. One study found that the shaft-neck and shaft-physis angles were overestimated on plain radiographs and neck torsion angles were underestimated when compared to measurements on computed tomography (CT)-based three-dimensional computer models of the same hip (28). The variability was high especially for neck and physeal torsional measurements with standard deviations of ±11.8 and ±16.7 degrees. It is therefore imperative that the surgeons be certain that radiographic method and patient positioning provide a reproducible and accurate depiction of the femoral geometry (28).

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|