48

Distal Interphalangeal Joint Dislocations

John D. Wyrick

History and Clinical Presentation

A 24-year-old right hand dominant man injured his right small finger while playing softball. The ball struck him on the tip of the finger and he thought he “only jammed” the finger. He describes pulling on the finger, which made it feel a little better, but always noted some deformity, which he attributed to swelling. He did not seek medical attention until 10 days after the injury. When seen, he described persistent pain and lack of motion as the main reasons for seeking help.

Physical Examination

Significant swelling diffusely throughout the right small finger is noted. It is more prominent distal to the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint. No wounds were present. Grossly, there was a prominence dorsally at the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint and obvious deformity. Due to pain his passive motion was not tested, but his active motion was 10 to 25 degrees. Sensibility testing revealed static two-point discrimination of 5 mm.

Imaging Studies

Biplanar radiographs showed a dorsal dislocation of the DIP joint. No fracture was present (Fig. 48–1).

Differential Diagnosis

DIP joint dislocation

Fracture of distal phalanx

Mallet injury

Avulsion of flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) tendon

PIP joint dislocation

PEARLS

- In a spontaneously reduced dislocation with an open wound, the joint must be explored and irrigated thoroughly.

PITFALLS

- Avoid chronic deformity and disability by testing active extension and flexion of the DIP joint after reduction.

Figure 48–1. Lateral radiograph after reduction attempt with persistent dorsal dislocation of distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint.

Diagnosis

Dislocation of the DIP Joint

Dislocations of the DIP joint are not commonly seen. More common is the dorsal PIP joint dislocation, which is the result of a hyperextension injury. Often these DIP joint injuries are reduced in the field and are never seen for medical attention.

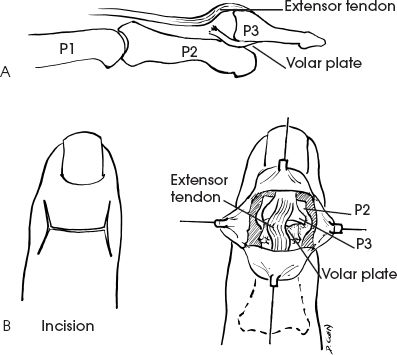

Most commonly the DIP dislocations are in the dorsal direction following hyperextension injuries. The joint is inherently quite stable because of the strong attachments of the two collateral ligaments and volar plate, which create a box-like confinement. The flexor and extensor tendons as well as the tight skin add further stability. The skin is so taut in this region that these injuries are often open with a palmar wound. If this is the case, the wound needs to be explored under adequate anesthesia to be certain there is no contamination in the joint, and to irrigate it well.

The diagnosis is usually straightforward. The major considerations in the differential diagnosis are various fractures around the DIP joint. These can easily be excluded by routine anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs both before and after reduction. Once reduction is obtained, it is very important to test the integrity of the extensor and flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) tendons, as either can be injured with the dislocation. If missed, these injuries can be extremely difficult to treat later.

Nonsurgical Management

It is extremely uncommon for these injuries to require surgery. After obtaining the appropriate radiographs and the diagnosis is made, the next step is administering an anesthetic. Lidocaine 1% without epinephrine is injected as a metacarpal block to anesthetize the radial and ulnar digital nerves and then injected dorsally subcutaneous at the base of the finger to block the dorsal sensory nerves. Usually only ∼4 to 5 cc are required. Once the patient is anesthetized, the reduction can usually be obtained with longitudinal traction and flexion of the DIP joint for dorsal dislocations. Sometimes an exaggeration of injury (e.g., hyperextension of the joint) may be necessary to reduce it. For the volarly displaced injuries, traction and extension are used for reduction.

Once the reduction is completed, the joint is first tested for stability, both passively and actively. Most important is to actively test the extension and flexion of the DIP joint. An extensor lag can be indicative of a mallet injury and needs to be splinted appropriately (see Case 38, Mallet Fractures). A mallet injury would be more likely with a volar dislocation. If the patient cannot actively flex the DIP joint, he or she may have an FDP avulsion, which needs urgent treatment like any flexor tendon injury.

After stability testing, AP and lateral radiographs need to be obtained (1) to confirm a concentric reduction and (2) to make sure no fractures have been missed.

These injuries are rarely unstable and thus need no splinting. If the patient is uncomfortable, then a removable splint can be applied for approximately 1 week. If there is instability, a splint should be fashioned to keep the joint in slight flexion. This should not be necessary for more than 3 weeks.

In the case presented here, attempted reduction under metacarpal block was unsuccessful. After a reduction attempt and splinting, radiographs appeared as in Figure 48–1.