Diagnostic Categories and Definitions for the Adult Hip

Gregory G. Polkowski

John C. Clohisy

Introduction

The last two decades have shown a substantial increase in knowledge regarding abnormal conditions that can affect the hip prior to the onset of advanced hip disease. This relatively young branch of “joint preservation surgery” of the hip has been driven by a variety of processes. Technologic advances that allow for advanced imaging of intra-articular structures of the hip joint including high resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), delayed gadolinium-enhanced MRI of cartilage (dGEMRIC) imaging, and three-dimensional computed tomography imaging (3D-CT) allow for noninvasive characterization of subtle joint structures. Similarly, more standardized methods of acquisition and interpretation of the plain radiographs of the hip and pelvis also allow for improved description of subtle morphologic differences in the hip joint structure. Improvements on the arthroscopic front have allowed for direct visualization of intra-articular structures. In addition to this, advances in open surgical techniques including periacetabular osteotomy surgery and a safe method to dislocate the hip without compromise to the femoral head blood supply have allowed for improved ability to treat structural hip problems, as well as visualize the effects that the structural abnormalities have on the subtle aspects of hip motion and joint function. These advances have led to improvements in the understanding of the pathomechanics of a variety of prearthritic hip conditions. There also has been an increase in the number of new terms used to describe certain aspects of hip disease in the young adult over recent years, and at times inconsistencies in use and meaning of such terms can be confusing and counterproductive. The purpose of this chapter is to review some of the diagnostic categories and terms used commonly in the evolving field of hip joint preserving surgery and to set the framework for some basic concepts and terminology that will be encountered by the reader in subsequent chapters of this work.

Clinical Situations/Diagnoses

Hip Dysplasia

“Hip dysplasia” is a problematic term meaning different things to different people, and it is not an inherently descriptive term. It is a term that tends to be used synonymously with several others, including developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), congenital dysplasia of the hip (CDH), and acetabular dysplasia. In its most general sense, hip dysplasia refers to an acetabulum that is excessively shallow in depth. The resulting unfavorable biomechanical effects on the ball-and-socket joint are that of abnormally high articular cartilage contact stresses within the acetabulum as a result of the structural instability that occurs because of the shallow socket. This clinical situation exists in several forms, which will be highlighted below. The unifying theme among these subsets of hip dysplasia is that of a volume-deficient shallow acetabulum, whereas the differences in these groups relates to the severity of disease and the presence or absence of femoral head deformity associated with the acetabular disease.

Classic Hip Dysplasia

Classic hip dysplasia refers to a hip in which a shallow acetabulum exists to the extent that there is structural hip instability ranging from femoral head subluxation to complete dislocation outside of the native acetabulum. It is this classic hip dysplasia that routine newborn physical examination screening is recommended to attempt to detect. The presence of a positive Ortolani sign (a palpable reduction of a posterior subluxated hip) is diagnostic for this condition in the newborn, and if left untreated, the end effect on acetabular development ranges from a high angle of acetabular inclination with femoral head subluxation to complete dislocation, which is usually associated with varying degrees of excessive femoral anteversion.

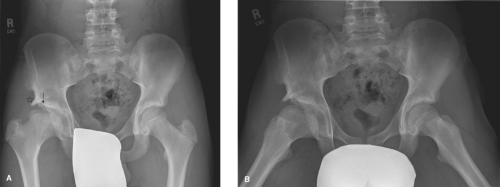

The associated radiographic findings of a hip with classic hip dysplasia are usually not subtle, with the hallmark finding being a break in Shenton line. The Crowe classification is useful in describing the extent of classic hip dysplasia, with grade 1 hips having superior subluxation of the femoral head less than 50%, grade 2 having subluxation 50% to 75%, grade 3 between 75% and 100%, and grade 4 subluxation greater than 100% (1). Figure 9.1 depicts a radiograph of a patient with Crowe 2 dysplasia and secondary osteoarthritis. Another useful classification system is the Hartofilakidis system in which three types of dysplasia are described: the

“dysplastic hip” remains contained within the original acetabulum with varying degrees of subluxation; the “low dislocation” hip has a femoral head that articulates with a false acetabulum, in which there is some overlap between the true and false acetabula; and the “high dislocation” hips have a femoral head that is completely outside of the true acetabulum with no overlap (2).

“dysplastic hip” remains contained within the original acetabulum with varying degrees of subluxation; the “low dislocation” hip has a femoral head that articulates with a false acetabulum, in which there is some overlap between the true and false acetabula; and the “high dislocation” hips have a femoral head that is completely outside of the true acetabulum with no overlap (2).

The natural history of hips with classic dysplasia is better defined than the other subgroups of hip dysplasia, with most cases in which subluxation is present resulting in secondary degenerative changes in hip osteoarthritis (3,4). In cases of complete dislocation of the femoral head (Crowe 4 hips), the presence of bilateral dislocations and the absence of a pseudoacetabulum have been shown to lead to better clinical results than in cases of unilateral disease or in hips in which a pseudoacetabulum exists (5,6).

Mild or Borderline Hip Dysplasia

Mild or borderline hip dysplasia represents the least severe form of hip dysplasia. The hallmark of this type of hip dysplasia is the presence of a shallow acetabulum in the absence of overt femoral head subluxation. The structural instability in this type of hip dysplasia is mild in comparison with classic hip dysplasia, and it usually does not become symptomatic until young adulthood, and in some cases may not cause symptoms until advanced hip arthritis ensues in later decades of life. These hips represent Hartofilakidis “dysplastic” hips.

Radiographic findings in the patient with mild or borderline hip dysplasia may be subtle, and the diagnosis may be missed by the casual observer (Fig. 9.2). A more precise quantification of acetabular depth and inclination is often necessary to characterize this type of dysplasia. Unlike classic dysplasia, in which femoral head subluxation is obvious, the radiographic characteristics of mild or borderline dysplasia are that of a lateral center-edge angle between 15 and 30 degrees, with an intact Shenton line. In most cases the femoral head remains congruent with the acetabulum in this form of hip dysplasia. Excessive femoral anteversion may also be present in hips with mild dysplasia, which may not be readily apparent on AP imaging. In addition, acetabular retroversion may be present in cases of mild dysplasia. Approximately one-sixth of hips with dysplasia were also noted to have evidence of acetabular retroversion with supine imaging on one study (7). Furthermore, retroversion was present in as many as one-third of patients in a more recent report that examined standing AP pelvis radiographs (8).

Figure 9.2. AP pelvis of a 37-year-old female with mild left hip dysplasia. Lateral center-edge angle measures 15 degrees, and the Tönnis angle measures 17 degrees. Shenton line remains intact. |

The natural history of mild hip dysplasia is not as well defined as it is for classic hip dysplasia, and this discrepancy is expected given the frequently subtle nature of the diagnosis, the fact that it has only become increasingly recognized over the course of the last two decades as a source of pain in the prearthritic hip, and possible precursor to early hip osteoarthritis. Similar to classic hip dysplasia, the ongoing theory regarding the pathomechanics for the development of secondary osteoarthritis for a hip with mild dysplasia is that the articular cartilage at the acetabular rim is exposed to much higher contact stress in the setting of a relatively shallow acetabulum which leads to early degeneration of the articular cartilage at this site. The introduction of the Bernese periacetabular osteotomy in 1988 by Ganz et al. (9), allows the surgeon to reduce the articular cartilage stresses at the periphery of the acetabulum by reorienting the hip socket providing more lateral and anterior coverage. The results of multiple case series highlighting the outcome of this procedure have shown significant reduction in hip pain and improvement in hip scores for patients with mild-to-moderate hip dysplasia, especially if these procedures are performed prior to the onset of secondary hip osteoarthritis (10).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree