ze and shape. There is no identifiable cause for primary chondromatosis. Milgram (

joint space widening did not improve after surgical treatment at final follow-up. Additional radiographic findings may include bony erosion, and osteophyte formation may present late in the disease (8,10,11,13).

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Diagnosis and Treatment of Synovial Disorders

Introduction

The synovial membrane serves to maintain the health of articular cartilage and increase lubrication. As such, the synovium constitutes the intimal layer of the joint capsule, which is in direct continuity with the joint. The synovium is a porous barrier that is composed primarily of two types of cells. Type A cells constitute approximately 10% to 20% of the cells and are bone marrow precursors and act as macrophages. Type B cells are fibroblast-like cells responsible for the production of hyaluronin. Below the synovial cells lies a vast network of fibroblasts, blood, and lymphatic vessels to facilitate gas and metabolite exchange.

Synovial diseases are rare disorders that affect large synovial joints. Successful management of these disorders mandates the proper and timely diagnosis of these conditions as well as appropriate surgical management of the disease and its possible sequelae. Delayed diagnosis or failure to treat can result in accelerated degenerative joint disease. The most commonly seen synovial disorders of the hip, other than rheumatologic and inflammatory arthritidies, include synovial chondromatosis and pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS).

Synovial Chondromatosis

Overview

Synovial chondromatosis is a rare condition due to cartilage production by the synovial membrane. Metaplastic mesenchymal cells in the synovial lining differentiate into chondroblasts. Recent studies that have suggested a defect in chromosome 6 may contribute to this condition (1). In addition, involvement of fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-9 and FGF receptor 3 may also play a role in an autocrine growth factor loop (2). The cartilage is produced and becomes pedunculated eventually becoming a loose body in the joint. The loose bodies are nourished by synovial fluid and can continue to grow. Secondary central calcifications are commonly seen in this disease (3).

Synovial chondromatosis can be classified as primary or secondary (4). The primary form is defined by small round loose bodies of uniform sia54d41f043ef9662084dbb6b8e841bd}/ID(R5-60)” title=”5″ onmouseover=”window.status=this.title; return true;” onmouseout=”window.status=”; return true;”>5) further differentiated primary chondromatosis into three phases. Phase 1 is characterized by intrasynovial lesions without evi7416ca7fe6c76f8a54d41f043ef9662084dbb6b8e841bd}/ID(R6-60)” title=”6″ onmouseover=”window.status=this.title; return true;” onmouseout=”window.status=”; return true;”>6,7). Patients commonly present from the second to the seventh decade of life. There is a 2:1 male predominance compared to females (7). Patients’ presenting complaints are often nonspecific and include pain, stiffness, swelling, and a limp. On physical examination, the patients usually demonstrated decreased range of motion, tenderness, and locking episodes (7,8). The diagnosis in the hip is more challenging than more superficial joints; however, since signs of synovial thickening, crepitus and palpable loose bodies are absent (9).

Imaging and Diagnosis

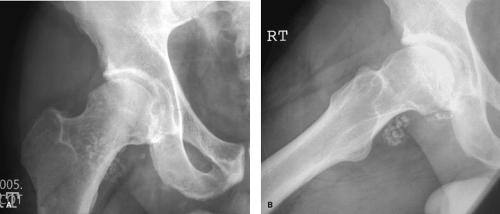

Plain radiographs may be helpful in detecting loose bodies; however, in 20% to 50% of cases, loose bodies cannot be appreciated since the loose bodies may be radiolucent (10,11,12,13) (11,12,13) (Fig. 60.1). Several studies have reported on joint space widening or hip subluxation in the setting of synovial chondromatosis (11,14). Yoon et al. demonstrated widening of the superior and medial joint spaces compared to the unaffected side in 12 of 21 (57%) patients. In addition, the

Further imaging is often required to make the diagnosis. Joint arthrography or computed tomography (CT) can be helpful in distinguishing loose bodies. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides a more reliable means of detecting intra- and extra-articular pathology as well as the presence of loose bodies (2,10,13).

Both open and arthroscopic approaches have been described for loose body removal and synovectomy. Open synovectomy has demonstrated decreased recurrence rates compared to previous approaches (8,17). Lim et al. (8) examined patients who underwent open arthrotomy with and without dislocations. There was no difference noted in pain relief between the two techniques. Two patients who underwent the arthrotomy alone required further surgery. One patient whs=”P”>Treatment of symptomatic synovial chondromatosis requires the removal of all the loose bodies. Complete synovectomy of the joint has been shown to lower rates of recurrence compared to removal of loose bodies alone (16,17). Recurrence rates can range between 10% and 20% in spite of surgical intervention (8,12).

Surgical findings are consistent with radiographic findings. Thickened, abnormal synovium, joint effusion, multiple loose bodies of various sizes that may be adhered to the synovium are often present at the time of surgery. The disease is most often noted in the peripheral compartment of the hip joint but can also be found in the central compartment with a reported incidence of 24% of cases (12) examined 111 patients who underwent arthroscopic synovectomy and loose body removal with a mean follow-up time of 78.6 months. Seventy-nine percent of patients required only one arthroscopic procedure whereas 31% required two or more procedures. In addition, 38% of patients required further open pro3362c21cc9ec01f975b9454417416ca7fe6c76f8a54d41f043ef9662084dbb6b8e841bd}/ID(R8-60)” title=”8″ onmouseover=”window.status=this.title; return true;” onmouseout=”window.status=”; return true;”>8,17). Lim et al. (8) examined patients who underwent open arthrotomy with and without dislocations. There was no difference noted in pain relief between the two techniques. Two patients who underwent the arthrotomy alone required further surgery. One patient who underwent a surgical hip dislocation developed avascular necrosis of the femoral head within 6 months requiring a total hip arthroplasty (THA). Ganz et al. (18) refined the technique of surgical hip dislocation such that a complete synovectomy can be achieved after a safe exposure of the acetabulum with access to the peripheral and central compartments while protecting the blood supply to the femoral head 19). Schoeniger et al. (17) published on a series of eight patients treated with this technique and demonstrated no local recurrence or femoral head osteonecrosis at 4-year follow-up. Two patients required THA at 5 and 10 years after the index procedures.

Arthroscopic loose body removal and synovectomy has demonstrated promising early results (20,21). Boyer and Dorfmann (<A onclick="if (window.scroll_to_id) { scroll_to_id(eve bursa. The etiology of PVNS is not well understood. Some evidence in the literature suggests that PVNS is a neoplasia. Recent work suggested clonal DNA rearrangement or possibly trisomy seven as a genetic lead to understanding PVNS (25,