Chapter 54 Critical Issues in Drug Development for SLE

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Characteristics Critical for Drug Development

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Is a Chronic Nonlethal Disease

Although a small number of patients suffer from severe and life-threatening complications of SLE, for the vast majority of patients the disease is characterized by chronicity without an immediately life-threatening character. In this regard, the distinctions made by Barr and colleagues,1 who noted the following three subsets of patients, are important: (1) patients with chronic active disease having continuously smouldering disease activity with or without superimposed flares; (2) patients with a disease characterized by symptom-free periods, punctuated by recurrent flares; and (3) patients exhibiting long quiescence or remission.2 The same patterns were observed in other large longitudinal studies.3 Needless to say, the clinical approach to these patients would differ quite significantly, with the first named group representing the most notable clinical challenges and unmet needs. Remarkably, however, the distinction among these patient profiles has not always been made sufficiently clear in drug development.

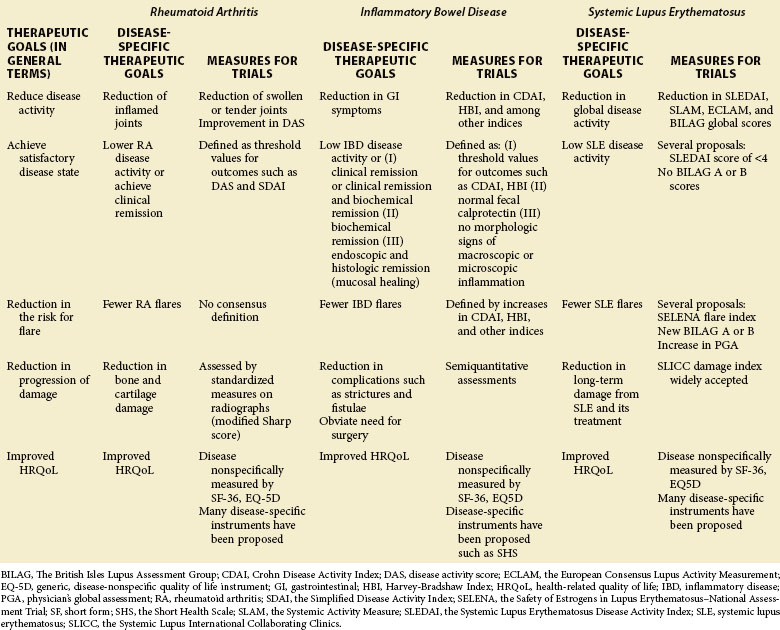

1. Reduction of the activity of the disease

2. Achievement of a satisfactory or acceptable disease activity state

3. Reduction of the risk for flare of the disease

4. Reduction of the progression of damage caused by the disease

5. Improvement in the health-related quality of life (as reported by the patient)

Table 54-1 shows these therapeutic goals and ways to measure them in clinical trials for RA, IBD, and SLE.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Is Associated with Significant and Incompletely Understood Detrimental Effects on Quality of Life

Both in large registries and during the course of clinical trials performed in recent decades, it has repeatedly been determined that health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is significantly reduced in patients with SLE.4–8 The decreases observed in trials were often of a magnitude that compares unfavorably with other chronic musculoskeletal diseases but is rather comparable to late-stage disease in chronic pulmonary, cardiac, or infectious conditions. The exact reasons for the striking impact that SLE has on HRQoL is as yet incompletely understood. The persistent activation of immunologic effector mechanisms may give rise to significant subjective symptoms in the form of fatigue, lack of energy, and lassitude; and these mechanisms may also have effects on cognition, mood, and other mental functions.9 Conversely, it has been suggested that many patients with SLE suffer from fibromyalgia,10,11 which proposes that these are two separate disease entities that co-exist in such patients. An alternative view has proposed that fibromyalgia may be a manifestation of SLE.12 Perhaps these distinctions cannot be fully resolved until the nature of the chronic symptoms such as those that occur in fibromyalgia and related conditions are more fully understood. In the individual patient case, it may be impossible to determine whether nonspecific subjective symptoms are due to mechanisms more directly related to the autoimmune process versus those that may be linked to other mechanisms including those at the level of the central nervous system.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Is Highly Heterogeneous in its Clinical Expression and Probably in its Underlying Pathophysiology

In contrast to diseases such as RA in which the central clinical manifestations are similar among patients and can be defined in terms that are applicable to all patients, SLE is characterized by a bewildering heterogeneity that makes it inevitable that patients have to be assessed in different ways, depending on a patient’s particular clinical situation. From a clinical trials point of view, this characterization presents an exceptionally large challenge. One possible solution to this dilemma is the use of generalized disease activity indices to measure the overall SLE activity, irrespective of the particular disease manifestation from which the patient may be suffering. The instruments developed for this purpose are discussed in the following text and are also discussed Chapter 46. However, approaching SLE trials with a different intention is also possible, namely to investigate patients with similar disease manifestations and focus the assessment on the outcome of that particular organ system or domain. The most well-studied example of this type of approach is lupus nephritis, for which a large number of trials have been performed. In such trials the patients are selected for significant disease activity in the renal system as defined by inclusion and exclusion criteria, and subsequent treatments are then assessed in terms of their ability to control that aspect of the disease. Whether or not other disease manifestations (i.e., in nonrenal organ systems) are also positively impacted is further assessed by appropriately chosen secondary outcome criteria. Although this particular strategy has so far been used almost exclusively for lupus nephritis, it is certainly conceivable that this approach could be used for other organ manifestations as well. For predominantly cutaneous SLE, using the same measures that are employed in dermatology clinical trials, for example, the Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Area and Severity Index (CLASI), is possible13; and for patients with predominant musculoskeletal disease manifestations in SLE, established arthritis scores such as those employed in clinical trials for RA might be used (e.g., the American College of Rheumatology [ACR] 20 response14 or responses based on the disease activity score [DAS]15). The subtle nuances of disease manifestations in SLE and how they differ from other conditions must then, of course, be considered.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree