Fig. 1

The iliopsoas tendon is formed from a confluence of the psoas and iliacus muscles at the level of the inguinal ligament. However, at the inguinal ligament level where the snapping occurs, the iliac muscle remains separated from the psoas tendon and muscle and then merges more distally with its tendon and joins the psoas tendon to become the “iliopsoas” tendon

Below the level of the inguinal ligament, the iliac and psoas muscle-tendon complex, which will be referred to as the iliopsoas muscle-tendon unit (MTU), crosses anterior to the pelvic brim and hip joint capsule in a groove between the iliopectineal eminence medially and the anterior inferior iliac spine laterally [12]. The iliopsoas MTU is separated from these structures by the iliopsoas bursa. The iliopsoas bursa, which is 5–6 cm long and 3–4 cm wide, extends from the level of the iliopectineal eminence to the lesser trochanter and is the largest bursa in the body.

It is important to note that the iliopsoas bursa communicates directly with the articular cavity of the hip joint in 15 % of individuals [12]. The presence of this communication should be documented by the radiologist at time of the patient’s MR arthrography. This is an important finding with regard to assessing the results of diagnostic, anesthetic hip joint injections. In patients with this communication, an anesthetic hip joint injection would anesthetized both the hip joint and the iliopsoas bursa, and thus, the anesthetic hip joint injection would be of little value for determining if one or both of these structures are the source of the patient’s “hip pain.”

The composition of the iliopsoas muscle-tendon unit (MTU), which varies throughout its course from its origin at the level of the inguinal ligament to its insertion on the lesser trochanter, has been defined at the level of the labrum, the femoral neck, and the lesser trochanter, the three sites where arthroscopic tenotomies currently are performed. Alpert et al. found that the iliopsoas tendon makes up 44 % of the MTU at the level of the labrum, and they advocated performing tenotomies at the labral level because they believed that releasing the tendon at the lesser trochanter would release the entire iliopsoas muscle belly-tendon complex [13]. However, Alpert’s study did not define the composition of the iliopsoas MTU or the percentage of the MTU that was released when the tendon was cut at the level of the femoral neck or lesser trochanter. Blomberg and associates performed a cross-sectional analysis of the iliopsoas MTU at the level of the labrum, the femoral neck, and the lesser trochanter and found that at the level of the labrum, the transcapsular (femoral neck) release site, and lesser trochanter, the iliopsoas MTU was composed of 40 % tendon/60 % muscle belly, 53 % tendon/47 % muscle belly, and 60 % tendon/40 % muscle belly, respectively (Table 1) [14]. Blomberg’s results documented that there is a significant (40 %) muscular component to the iliopsoas MTU attachment to the lesser trochanter and that performing a tenotomy at that site does not release the entire muscle belly-tendon complex.

Table 1

The average circumference of the 40 iliopsoas tendons and muscle-tendon units (MTUs) at the level of the labrum, the transcapsular release site, and the lesser trochanter

Level of measurement | Tendon average circumference (mm) | MTU average circumference (mm) | Tendon percentage of the MTU (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

Labrum | 27.1 | 68.3a | 39.7b |

Transcapsular | 31.0 | 58.0a | 53.4b |

Lesser trochanter | 27.5 | 45.7a | 60.2b |

Blomberg’s findings are in agreement with the results of an earlier anatomical study by Tatu et al. which noted that the most lateral fibers of the iliac muscle inserted, without any tendon, on the anterior surface of the lesser trochanter and infratrochanteric region [12]. They also identified an ilio-infratrochanteric muscular bundle that ran along the anterolateral edge of the iliacus muscle and inserted without any tendon onto the anterior surface of the lesser trochanter and the infratrochanteric region. Thus, they documented that the iliopsoas MTU had both a muscular and tendinous attachment to the lesser trochanter. It is clear from the results of these two studies that performing a tenotomy at that lesser trochanter will not release the entire muscle belly-tendon complex.

Clinical Presentation

The internal (iliopsoas) snapping hip syndrome is characterized by an audible or palpable snap in the anterior area of the hip, and it occurs without symptoms in 10 % of young active individuals. In asymptomatic individuals, no treatment is required. Symptomatic individuals with this problem typically report a painful snapping in their hip that they localize to the anterior and medial groin area. Their “hip” pain is usually exacerbated by active hip flexion and activities that require extension of the flexed, abducted, and externally rotated hip. Painful snapping iliopsoas tendons most often occur in young, physically active individuals and are common in sports that demand repeated abduction of the leg above waist level. This may be the due to the wide range of hip motion that individuals must generate in such activities as karate and ballet. Other aggravating activities include: walking, running, kicking a ball, climbing stairs, putting on socks, and rising from a chair. Patients often note that they have dull, achy anterior groin pain immediately following the “snapping” of their hip and that their pain and snapping diminish with decreased activity and rest.

On physical examination, patients with a painful, snapping tendon may keep their knee flexed during heel-strike and midstance phases of gait. The painful snapping can often be reproduced by placing the affected hip in a flexed (30°), abducted, and externally rotated position and then extending the hip to a neutral position. Patients with associated iliopsoas tendinitis will have pain with a resisted straight-leg test and tenderness to palpation of the psoas muscle-tendon complex just below the inguinal ligament [4, 6, 15–17].

Individuals with iliopsoas impingement (IPI) may or may not report snapping in their hip. Domb et al. noted that all patients with iliopsoas impingement have anterior hip pain and pain with active flexion, but most do not experience snapping sensations [11]. In these patients, physical examination reveals focal tenderness over the iliopsoas tendon, a positive impingement test, and pain with a resisted straight-leg test. However, this constellation of clinical findings is common with labral pathology and femoroacetabular impingement and is not specific to the diagnosis of iliopsoas impingement. Thus, the diagnosis of iliopsoas impingement is made at arthroscopy and is based on the findings of an isolated, anterior (3 o’clock) labral injury that is located directly adjacent to the iliopsoas tendon [11].

Imaging Studies

As previously noted, distinguishing between the internal (snapping iliopsoas tendon) and intra-articular (e.g., labral tear) causes of a snapping hip often is difficult because these two conditions have many of the same clinical findings. Thus, most patients with chronic painful snapping hips and a clinical examination consistent with either an internal or intra-articular causation have both magnetic resonance arthrography of their hip and an ultrasound evaluation of the iliopsoas tendon performed. However, standard radiographs of the involved hip should be obtained prior to ordering any ancillary imaging studies.

Standard Radiographs

All individuals with painful, snapping hips should have standard radiographs of the symptomatic hip that include an anteroposterior view of the pelvis and a cross-table or elongated-neck lateral view (hip in 90° of flexion and 20° of abduction) of the affected hip. These radiographic views may identify such intra-articular causes of snapping as loose bodies, os acetabuli, or a calcified labrum. The plain radiographs also will evaluate the patient’s pelvis and proximal femur for evidence of femoroacetabular (bony) impingement, degenerative joint disease, and other bony abnormalities.

Ancillary Imaging Studies

After plain films have been completed and evaluated, magnetic resonance imaging usually is the first ancillary study performed. The details of the author’s MRI and ultrasound imaging protocols have been previously reported [4, 17] and are summarized below. Immediately preceding the MR arthrography and ultrasound-guided psoas bursa injections, patients are given a pain “circle” diagram (PCD) to complete that indicates the sites of their “hip pain.” Ten to 30 min after their injection, they complete a second PCD that indicates at which sites their pain was relieved (Fig. 2) [18]. The patients are then counseled that their areas of “hip pain” that were not transiently relieved by the injections will not be relieved by hip arthroscopy . The PCD combined with the anesthetic injections of the hip joint and iliopsoas bursa has helped physicians reconcile the often unrealistic expectations of those patients with labral tears and snapping tendons who believe that hip arthroscopy also will treat all of their pelvic, buttock, and back pain.

Fig. 2

The pain “circle” diagram (PCD) has circles that the patients put an “X” in to indicate if they have pain in that area. The areas include the anterior superior spine (A), greater trochanter (B), central groin (C), symphysis pubis (D), proximal inner thigh (E), anterior thigh (F), posterior iliac crest (G), sacroiliac joint (H), sciatic notch (I), and ischial tuberosity (J). The circled areas represent the anatomic locations associated with hip pain

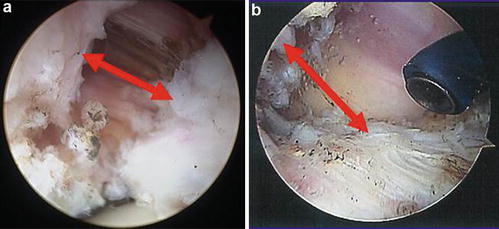

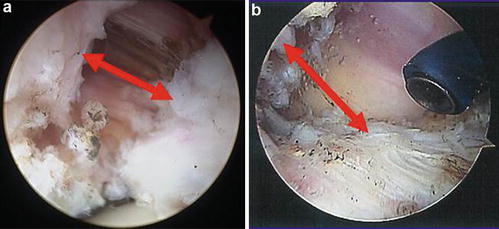

Fig. 3

(a, b) Arthroscopic views of the tendon separation that occurred after labral level (a) and lesser trochanteric (b) iliopsoas tenotomies. The arrows indicate where the separation measurements were made. After a labral-level tenotomy, the tendon separated an average of 0.83 cm. After a lesser trochanteric tenotomy was performed, the tendon separated an average of 1.33 cm. The 0.5 cm difference in the amount of tendon separation between the two groups was statistically significant at the p < 0.001 level

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Prior to imaging, the hip is injected with a standard solution of a long-acting anesthetic and contrast. MR arthrography is preferred because several studies have shown that (1) MR imaging without intra-articular contrast has a lower sensitivity and accuracy for detecting labral pathology [19–21] and (2) pain relief from an intra-articular anesthetic injection confirms that the source of pain is from within the hip joint [21–25]. MR arthrography (MRA) also is useful for detecting labral tears and other intra-articular causes of joint pain. Labral tears have been diagnosed on preoperative MRA and found during hip arthroscopy in up to 70 % of patients with a painful, snapping iliopsoas tendon [4, 17].

Ultrasound Evaluations

If a patient has no or minimal relief of their hip pain after their MRA, they subsequently (1 or more weeks after the hip arthrogram) have an ultrasound evaluation of their hip that includes static and dynamic (real-time imaging) of their psoas tendon and injection of anesthetic and steroid into their psoas bursa. Static images of the iliopsoas tendon are obtained to evaluate for tendon thickening, an enlarged bursa, and a peritendinous fluid collections. Color Doppler imaging of the iliopsoas may be performed to look for hyperemia as a sign of tendinous or peritendinous inflammation. Imaging of the asymptomatic contralateral hip should be performed to assess for any differences in appearance of the iliopsoas tendon. Studies have found that in a majority (95 %) of the cases, static images were normal. In the remaining 5 %, the static images demonstrated iliopsoas bursitis and/or tendinitis [4, 17].

Dynamic, real-time imaging of the tendon is performed because prior sonography studies have documented that an abnormal, sudden jerky motion of the iliopsoas tendon occurs in patients with a snapping hip [7, 26]. Several studies have found that in symptomatic patients, real-time imaging of the tendon will demonstrate snapping of the tendon in ~85 % of the cases [27–29]. This abnormal motion of the iliopsoas tendon can also be demonstrated radiographically by iliopsoas bursography or tenography followed by fluoroscopy [27, 28]. However, sonography is the preferred technique for examining the iliopsoas tendon because it allows both static and dynamic evaluation of the tendon [7, 29].

Following the dynamic evaluation of the iliopsoas tendon, a diagnostic, anesthetic injection of the iliopsoas bursa often is performed with the following protocol [30]. Using real-time imaging, a 22-gauge needle is passed into the iliopsoas bursa, and a 7 cc mixture of 3.5 cc of 0.5 % bupivacaine hydrochloride (Abbott Laboratories, N Chicago, IL) and 3.5 cc of 1 % lidocaine hydrochloride (Abbott Laboratories, N Chicago, IL) is injected into the bursa. Patients are asked to rate their pain level (scale 0–10) prior to the injection and immediately following the injection. If their pain is relieved, they are instructed to perform, within the next 2–4 h, the activities that previously had been painful and record their level of discomfort with each activity. These ultrasound-guided anesthetic injections will produce immediate pain relief in 89 % of patients with sonographically demonstrated snapping tendons [30]. With the addition of 1 cc of Kenalog-40 to the bupivacaine-lidocaine mixture, the injections have produced good and sustained (4 months–1 year) pain relief in a high percentage (~88 %) of patients with painful, snapping tendons [30–32]. If the ultrasound-steroid injections fail to produce sustained pain relief from the snapping of the tendon, further nonoperative treatment is pursued.

Nonoperative Treatment

Initial treatment for a painful, snapping iliopsoas tendon is rest, stretching exercises, oral anti-inflammatory medications, and focal treatment including iontophoresis and ultrasound [1, 5, 9, 33, 34]. Jacobson and Allen reported that “…stretching exercises involving hip extension for 6–8 weeks are generally successful in alleviating symptoms” [9]. Taylor and Clarke reported that 8 (36 %) of the 22 patients referred to them for a “snapping psoas” improved and did not require surgery after 6 weeks of rest and physiotherapy, which included assisted extension and ultrasound [34]. In Gruen et al.’s series of 30 patients, all patients received at least a 3-month period of stretching of the iliopsoas tendon, concentric strengthening of the hip internal/external rotators, and eccentric strengthening of the hip flexors and extensors. Nineteen patients (63 %) improved and did not require further intervention [33].

Injection of the iliopsoas bursa with anesthetic and steroids also has been advocated for treatment of this problem [28, 30, 31, 34, 35]. Wahl et al. reported on the results of bursal injections in two professional athletes who developed progressive iliopsoas tendon snapping as a result of vigorous drills and exercises. In both cases, ultrasound-guided intrabursal injections of steroids resulted in a return to football 4 weeks later without pain and long-term (26 months) resolution of the snapping [31]. Vaccaro et al. reported similar results on eight patients with painful snapping iliopsoas tendons that had cortisone injections into their psoas bursa [28]. Although 7 of the 8 patients obtained 2–8 months of pain relief from the injection, four patients eventually underwent surgery. In the largest series of bursal injections published to date, Blankenbaker et al. reported that 16 of 18 patients with painful snapping tendons had prolonged (≥3 months) relief after steroid injections into their iliopsoas bursa [30]. In those cases where steroid injections and physical therapy fail to relieve painful snapping of the tendon, operative treatment often is recommended.

Operative Treatment

The traditional surgical techniques described for the treatment of painful hips due to recurrent snapping of the iliopsoas tendon have been open procedures that include either a release of the tendon [8, 34, 35] or a lengthening of the iliopsoas muscle-tendon unit [1, 5, 9, 27, 28, 33]. Complications from these procedures have been reported to occur in 43–50 % of the patients [1, 5, 9]. The problems reported with these surgical approaches are summarized in Table 2 and include: (1) recurrent snapping of the tendon, (2) persistent hip pain, and (3) sensory nerve injuries due to the surgical incision. In Hoskins et al.’s study of 92 patients that had open fractional lengthening of their iliopsoas tendon, there were 40 complications, and 28 % of the complications were related to the incision required to perform the procedure [5]. Thus, an arthroscopic release of the iliopsoas tendon was introduced as an adjunct to hip arthroscopy for operative treatment of this problem, and to date, the results of this minimally invasive arthroscopic procedure have been excellent and better than those reported for open methods [4, 6, 15–17].

Table 2

Comparison of the postoperative complications reported with the open surgical procedures that have been used to treat painful snapping of the iliopsoas tendon

Study (year) | No. hips | Procedure | Persistent pain | Recurrent snapping | Flexor weakness | Wound problems |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Taylor (1995) [34] | 16 | Tendon release (medial approach) | 5 | 6 | 2 | 0 |

Dobbs (2002) [3] | 11 | Tendon lengthening (iliofemoral incision) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

Gruen (2002) [33] | 12 | Tendon lengthening (ilioinguinal incision) | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

Hoskins (2004) [5] | 92 | Tendon lengthening (iliofemoral incision) | 6 | 20 | 3 | 11 |

Totals | 131 | 17 | 27 | 10 | 13 |

The first arthroscopic iliopsoas tendon releases were performed at the lesser trochanter, and published studies have documented that an arthroscopic release of the tendon at this level will provide long-term relief from painful snapping of the tendon [4, 6, 15, 16]. The results of arthroscopic iliopsoas tenotomies performed at the lesser trochanter are summarized in Table 3. In 2005, Byrd published two articles describing the technique of endoscopic release of the tendon [15, 16] and noted that his preliminary experience in nine cases “had been quite good.” Although the length of follow-up was not stated, he reported that there was 100 % resolution of snapping and patient satisfaction, with no complications. In that same year, Ilizaliturri et al. reported on six patients who underwent an endoscopic lesser trochanteric release of the iliopsoas tendon for internal snapping hip syndrome [6]. Over the 10–27-month follow-up period, none of the patients had recurrence of their snapping symptoms. Although all patients noted a significant loss of flexion strength after surgery, their strength had improved by 8 weeks. In a subsequent publication, Flanum et al. reported that six patients who had an endoscopic iliopsoas tendon release had excellent results [4]. Their preoperative modified Harris hip scores averaged 58 points. After surgery, all patients had hip flexor weakness, used crutches for 4–5 weeks, and had 6-week scores that averaged 62 points. The patients continued to improve, and at 6 and 12 months, their scores averaged 90 and 96 points, respectively, and none had recurrence of their snapping or pain [4].

Table 3

Comparison of the published results of arthroscopic iliopsoas tenotomies performed at the lesser trochanter

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree