Chapter 31 Congenital Anomalies of the Trunk and Upper Extremity

This chapter discusses congenital elevation of the scapula, congenital torticollis, and congenital pseudarthrosis of the clavicle, radius, and ulna. Congenital anomalies of the hand and certain other anomalies of the forearm are discussed in Chapter 79. Congenital conditions of the spine are discussed in Chapters 40, 41, and 44.

Congenital Elevation of the Scapula (sprengel Deformity)

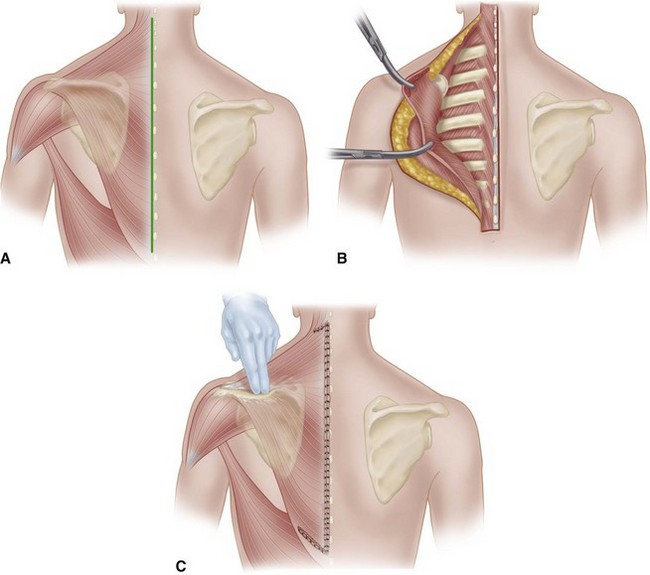

Woodward described transfer of the origin of the trapezius muscle to a more inferior position on the spinous processes. Greitemann, Rondhuis, and Karbowski recommended the Woodward procedure for patients with impaired function; for patients with only cosmetic problems, resection of part of the superior angle of the scapula was preferred. They suggested that better results are obtained with the Woodward procedure because (1) the muscles are incised farther from the scapula, which lowers the risk of formation of a scar-keloid that may fix the scapula in poor position; (2) a larger mobilization is possible; and (3) the postoperative scar is not as thick as with Green’s procedure. Borges et al. added excision of the prominent superomedial border of the scapula to the Woodward procedure. We generally prefer the Woodard procedure (see later) (Fig. 31-1).

Woodward Operation

Place the patient prone on the operating table, and prepare and drape both shoulders so that the involved shoulder girdle and the arm can be manipulated and the uninvolved scapula can be inspected in its normal position.

Place the patient prone on the operating table, and prepare and drape both shoulders so that the involved shoulder girdle and the arm can be manipulated and the uninvolved scapula can be inspected in its normal position.

Make a midline incision from the spinous process of the first cervical vertebra distally to that of the ninth thoracic vertebra (Fig. 31-2A). Undermine the skin and subcutaneous tissues laterally to the medial border of the scapula.

Make a midline incision from the spinous process of the first cervical vertebra distally to that of the ninth thoracic vertebra (Fig. 31-2A). Undermine the skin and subcutaneous tissues laterally to the medial border of the scapula.

Identify the lateral border of the trapezius in the distal end of the incision, and by blunt dissection separate it from the underlying latissimus dorsi muscle.

Identify the lateral border of the trapezius in the distal end of the incision, and by blunt dissection separate it from the underlying latissimus dorsi muscle.

By sharp dissection, free the fascial sheath of origin of the trapezius from the spinous processes.

By sharp dissection, free the fascial sheath of origin of the trapezius from the spinous processes.

Identify the origins of the rhomboideus major and minor muscles, and by sharp dissection free them from the spinous processes.

Identify the origins of the rhomboideus major and minor muscles, and by sharp dissection free them from the spinous processes.

Free the rhomboids and the superior part of the trapezius from the muscles of the chest wall anterior to them.

Free the rhomboids and the superior part of the trapezius from the muscles of the chest wall anterior to them.

Retract the freed sheet of muscles laterally to expose any omovertebral bone or fibrous bands attached to the superior angle of the scapula.

Retract the freed sheet of muscles laterally to expose any omovertebral bone or fibrous bands attached to the superior angle of the scapula.

By extraperiosteal dissection, excise any omovertebral bone, or if the bone is absent, excise any fibrous band or contracted levator scapulae; avoid injuring the spinal accessory nerve, the nerves to the rhomboids, and the transverse cervical artery.

By extraperiosteal dissection, excise any omovertebral bone, or if the bone is absent, excise any fibrous band or contracted levator scapulae; avoid injuring the spinal accessory nerve, the nerves to the rhomboids, and the transverse cervical artery.

If the supraspinous part of the scapula is deformed, resect it along with its periosteum; this releases the levator scapulae (if not already excised), allowing the shoulder girdle to move more freely (Fig. 31-2B).

If the supraspinous part of the scapula is deformed, resect it along with its periosteum; this releases the levator scapulae (if not already excised), allowing the shoulder girdle to move more freely (Fig. 31-2B).

Divide transversely the remaining narrow attachment of the trapezius at the level of the fourth cervical vertebra.

Divide transversely the remaining narrow attachment of the trapezius at the level of the fourth cervical vertebra.

Displace the scapula along with the attached sheet of muscles distally until its spine lies at the same level as that of the opposite scapula (Fig. 31-2C).

Displace the scapula along with the attached sheet of muscles distally until its spine lies at the same level as that of the opposite scapula (Fig. 31-2C).

While holding the scapula in this position, reattach the aponeuroses of the trapezius and rhomboids to the spinous processes at a more inferior level.

While holding the scapula in this position, reattach the aponeuroses of the trapezius and rhomboids to the spinous processes at a more inferior level.

In the distal part of the incision, create a fold in the origin of the trapezius and either excise the excess tissue or incise the fold and overlap and suture in place the resultant free edges.

In the distal part of the incision, create a fold in the origin of the trapezius and either excise the excess tissue or incise the fold and overlap and suture in place the resultant free edges.

FIGURE 31-2 Woodward operation for congenital elevation of scapula. A, Elevation of scapula, extensive origin of trapezius, and skin incision are shown. B, Skin has been incised in midline. Origins of trapezius and of rhomboideus major and minor have been freed from spinous processes, and these muscles have been retracted laterally. Levator scapulae, any omovertebral bone, and any deformed superior angle of scapula are to be excised. C, Remaining narrow attachment of trapezius superiorly has been divided at level of C4. Scapula and attached sheet of muscles have been displaced inferiorly, and aponeuroses of trapezius and rhomboids have been reattached to spinous processes at more inferior level. A redundant fold of trapezius aponeurosis is formed inferiorly. Fold of trapezius aponeurosis has been incised, and resultant free edges have been overlapped and sutured in place. Free superior edge of trapezius also has been sutured. SEE TECHNIQUE 31-1.

(Modified from Woodward JW: Congenital elevation of the scapula: correction by release and transplantation of muscle origins: a preliminary report, J Bone Joint Surg 43A:219, 1961.)

Morcellization of the Clavicle

Make a straight incision over the clavicle extending from 1.5 cm lateral to the sternoclavicular joint to 1.5 cm medial to the acromioclavicular joint.

Make a straight incision over the clavicle extending from 1.5 cm lateral to the sternoclavicular joint to 1.5 cm medial to the acromioclavicular joint.

Expose the clavicle subperiosteally.

Expose the clavicle subperiosteally.

Divide the bone 2 cm from each end, remove it, and cut it into small pieces (morcellize).

Divide the bone 2 cm from each end, remove it, and cut it into small pieces (morcellize).

Replace the pieces in the periosteal tube, and close the tube with interrupted sutures.

Replace the pieces in the periosteal tube, and close the tube with interrupted sutures.

Close the subcutaneous tissues and skin in a routine manner.

Close the subcutaneous tissues and skin in a routine manner.

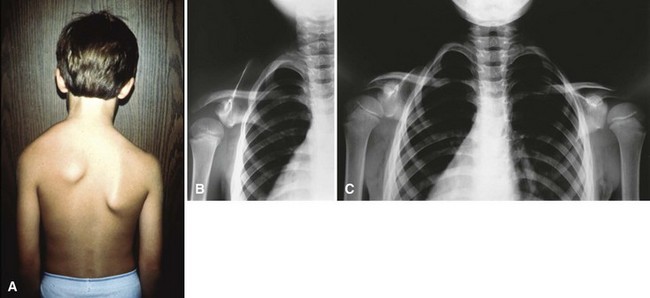

Congenital Muscular Torticollis

Congenital muscular torticollis (CMT) is caused by fibromatosis within the sternocleidomastoid muscle. A mass either is palpable at birth or becomes so, usually during the first 2 weeks. Congenital muscular torticollis is more common on the right side than on the left side. It may involve the muscle diffusely, but more often it is localized near the clavicular attachment of the muscle. The mass attains maximal size within 1 or 2 months and may remain the same size or become smaller; usually, it diminishes and disappears within 1 year. If it fails to disappear, the muscle becomes permanently fibrotic and contracted and causes torticollis, which also is permanent unless treated (Fig. 31-3).

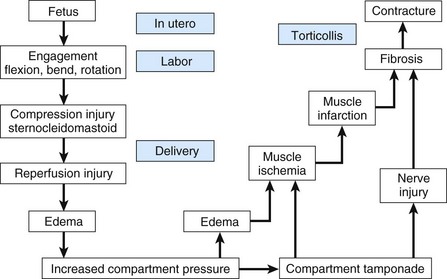

Various hypotheses of the cause of CMT include malposition of the fetus in utero, birth trauma, infection, and vascular injury. Davids, Wenger, and Mubarak found that MRI of 10 infants with CMT showed signals in the sternocleidomastoid muscle similar to signals observed in the forearm and leg after compartment syndrome. Further investigation included cadaver dissections and injection studies that defined the sternocleidomastoid muscle compartment; pressure measurements of three patients with CMT that confirmed the presence of this compartment in vivo; and clinical review of 48 children with CMT that showed a relationship between birth position and the side affected by contracture. These findings led the authors to postulate that CMT may represent the sequela of an intrauterine or perinatal compartment syndrome (Fig. 31-4).

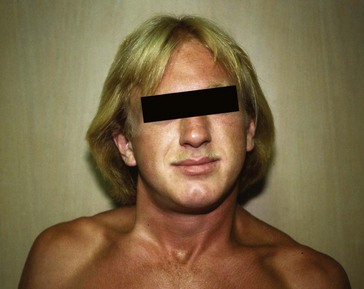

Any permanent torticollis slowly becomes worse during growth. The head becomes inclined toward the affected side and the face toward the opposite side. If the deformity is severe, the ipsilateral shoulder becomes elevated and the frontooccipital diameter of the skull may become less than normal. Such severe deformity could and should be prevented by surgery during early childhood. Ideally, surgery is performed just before school age so that sufficient growth remains for remodeling of facial asymmetry while giving enough time for the growth of the structures to make surgical dissection and release easier. Many patients are first seen only after the deformities have become fixed, and the remaining growth potential is insufficient to correct them (Fig. 31-5). Nevertheless, many authors have suggested that surgical release in older children can be successful and should be attempted even if the child presents later. The clinical results are significantly less successful in children who have finished growth than in children who still have growth remaining; however, most patients have marked improvement in neck motion and head tilt, with satisfactory functional and cosmetic results.

FIGURE 31-5 Untreated torticollis (right) in 19-year-old man; note limited rotation and plagiocephaly.

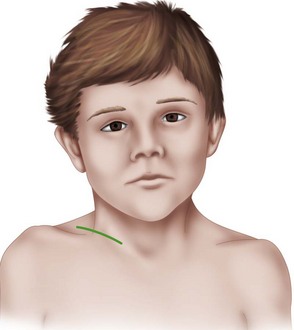

Unipolar Release

Make an incision 5 cm long just superior to and parallel to the medial end of the clavicle (Fig. 31-6), and deepen it to the tendons of the sternal and clavicular attachments of the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

Make an incision 5 cm long just superior to and parallel to the medial end of the clavicle (Fig. 31-6), and deepen it to the tendons of the sternal and clavicular attachments of the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

Incise the tendon sheath longitudinally, and pass a hemostat or other blunt instrument posterior to the tendons.

Incise the tendon sheath longitudinally, and pass a hemostat or other blunt instrument posterior to the tendons.

By traction on the hemostat, draw the tendons outside the wound and superior and inferior to the hemostat; clamp them and resect 2.5 cm of their inferior ends. If it is contracted, divide the platysma muscle and adjacent fascia.

By traction on the hemostat, draw the tendons outside the wound and superior and inferior to the hemostat; clamp them and resect 2.5 cm of their inferior ends. If it is contracted, divide the platysma muscle and adjacent fascia.

With the child’s head turned toward the affected side and the chin depressed, explore the wound digitally for any remaining bands of contracted muscle or fascia; and if any are found, divide them under direct vision until the deformity can, if possible, be overcorrected.

With the child’s head turned toward the affected side and the chin depressed, explore the wound digitally for any remaining bands of contracted muscle or fascia; and if any are found, divide them under direct vision until the deformity can, if possible, be overcorrected.

If after this procedure overcorrection is not possible, make a small transverse incision inferior to the mastoid process and carefully divide the muscle near the bone. Avoid damaging the spinal accessory nerve.

If after this procedure overcorrection is not possible, make a small transverse incision inferior to the mastoid process and carefully divide the muscle near the bone. Avoid damaging the spinal accessory nerve.

Close the wound, and apply a bulky dressing that holds the head in the overcorrected position.

Close the wound, and apply a bulky dressing that holds the head in the overcorrected position.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree