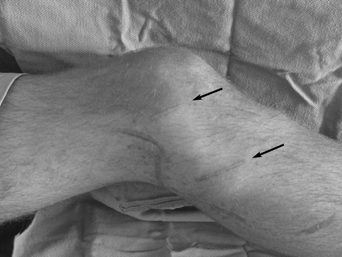

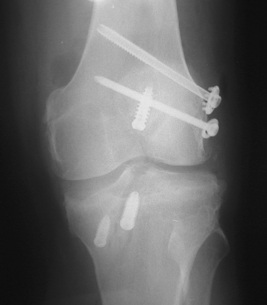

9 Although I have found that the risk of complications in the face of posterolateral knee injuries is relatively small, most of these injuries occur in combination with other ligament injuries or knee dislocations. The problems associated with these combined injuries need to be recognized when doing a posterolateral corner repair or reconstructive procedure. In an acute situation, we always try to perform the repair within the first 2 weeks after the injury, but there are circumstances that may prevent that. In the acute, severely injured knee, it must be determined that the skin over the posterolateral corner of the knee has minimal chance of skin slough, infection, or localized skin necrosis prior to proceeding with surgery. In addition, it is important to make sure that there has not been an associated open knee dislocation with the potential for infection, or significant abrasions over the posterolateral corner of the knee, which could also increase the risk of infection. In those cases in which there is concern for a potential degloving-type injury over the posterolateral corner of the knee, it is appropriate to wait until the skin showed evidence of healing and the hematoma is resolved before attempting a posterolateral corner surgical procedure. In an open knee dislocation or a significant abrasion over the posterolateral corner of the knee, it is prudent to wait until the skin is healed and all hematologic studies show no evidence of active or residual infection present. Our standard blood laboratory workup includes a C-reactive protein level, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and a complete blood count with differential. Any elevation of these laboratory values needs to be worked up further to make sure there is no residual infection present. Figure 9-1 Loosely applied Steri-Strips over an acute posterolateral repair postoperatively (right knee). In addition to the risk of skin breakdown in the acute situation, it is also important to recognize that significant postoperative swelling can develop in some of these patients. For this reason, it is important to stress that Steri-Strips placed over the surgical incision should be loosely applied (Fig. 9-1). If an assistant applies Steri-Strips tightly to hold the skin edges together, postoperative swelling could result in tension and blistering of the skin, which could lead to long-term skin discoloration in this area or wound breakdown. Although a small amount of blistering might be inevitable for some of these severe injuries, it is important to be proactive and to apply the Steri-Strips very loosely rather than use them to pull the skin margins together. In the face of chronic posterolateral knee revision reconstructions, the placement of previous skin incisions may make it difficult to perform an adequate surgical approach without crossing the skin incisions. In this circumstance, I have found it is better to incorporate the previous incision rather than to make an acute angled incision across previous incisions. In addition, it may be possible to use small horizontal incisions for an isolated fibular collateral ligament reconstruction (Fig. 9-2). These issues should be discussed with the patient beforehand. Although I have not seen patients with wound breakdown in these circumstances, I have noted some mild cases of postoperative cellulitis develop in these skin flap areas, which indicates that there is a poor blood supply in the tissue flaps. These surgical wounds must be closely monitored postoperatively. In some instances, we limit the range of motion for a longer period of time, up to 2 to 3 weeks, in these patients to make sure there is no skin breakdown in the areas of a previous incision. In our series, we found that about 15% of patients with posterolateral knee injuries present with a known common peroneal nerve motor or sensory deficit.1 In addition, I found that a higher percentage of patients show some intrasubstance hemorrhage, bulbous swelling of the common peroneal nerve, or significant scar tissue formation along the common peroneal nerve at the time of surgery. It is important to perform a thorough physical examination of the sensory function of this nerve prior to any surgical procedures so that proper preoperative documentation of the status of the nerve is recorded that can be followed postoperatively. Figure 9-2 A right knee showing the location of surgical incisions (arrows) for an isolated fibular collateral ligament reconstruction after an open knee laceration that injured it. In those cases in which we find a complete nerve avulsion at the time of surgery, a silk suture is tied around the ends of the nerve to identify it in the event of future nerve grafting procedures. However, in spite of seeing multiple attempts at cable grafts to reconstruct the function of the common peroneal nerve, I have not noted any patients who have had any more than a slight increase in the sensory innervation after these nerve graft procedures. I have not noted any patient to have an increase in motor function. In this regard, for patients who have evidence of a complete avulsion or tear of their common peroneal nerve at the time of surgery (Fig. 9-3), we recommend either a posterior tibialis tendon transfer at the same time of the initial surgery or a staged tendon transfer at 3 months postoperatively to treat their footdrop. Foot and ankle specialists are efficient in performing this tendon transfer. I have found that it significantly improves almost all patients’ function so that they do not need the use of an ankle-foot orthosis and have a fairly normal gait pattern after the posterior tibialis tendon transfer. In those acute knees that are found to have some evidence of swelling or injury to the nerve and that are noted to have some increasing motor or sensory deficits in the immediate postoperative period, we first remove the surgical dressings to try to minimize swelling around the knee. If this does not result in a resolution of the symptoms within 2 hours, we then flex the knee to 90 degrees to relieve any potential traction on the nerve. I have found that this occurs very rarely in our treated patients. The one case that I remember was a very thin young woman who had a four-ligament acute knee dislocation after a snowmobile accident and developed a common peroneal nerve complete motor and sensory nerve neuropraxia overnight after all of her ligaments were reconstructed. Because I followed this protocol, she had complete return of motor and sensory function within 6 weeks postoperatively. At her 2-year follow-up, she had no residual problems. Figure 9-3 Lateral view of a right knee demonstrating both a bulbous (A) and avulsed (in pickups) (B) common peroneal nerve as part of the exposure for a severe posterolateral corner knee injury. During the surgical approach for chronic posterolateral corner injuries, it is not uncommon to find the common peroneal nerve completely encased in scar. This can be very problematic as it can add significant surgical time to the case. In addition, when the nerve is completely encased in scar, it is difficult to determine where the nerve begins and the scar tissue ends. In these circumstances, I attempt to find the common peroneal nerve either proximally, where it is just coursing under the long head of the biceps femoris, or distally, where it is just posterior to the fascia and muscle attachments of the peroneus longus muscle, at the fibular shaft. An Adson tipped hemostat is very effective in performing a common peroneal nerve neurolysis in these circumstances. It is recommended to proceed very slowly for this part of the neurolysis to obtain, at a minimum, enough decompression of the nerve such that one can gain access to the fibular head and styloid and the posterior aspect of the tibia to drill the surgical tunnels for the reconstructive procedure. I have not noted any patients who have had objective motor or sensory deficits of the common peroneal nerve after these chronic reconstruction procedures. As in all major knee injuries, there is an increased risk for deep venous thrombosis in patients who have a posterolateral corner injury, whether it is treated in isolation or combined with other ligament injuries around the knee. Because these patients are treated with a non-weight-bearing protocol immediately after surgery for 6 weeks, they are treated prophylactically with enteric-coated aspirin, one daily, during this 6-week period. For those patients who have an allergy to aspirin, other factors that place them at a higher risk of deep venous thrombosis, or a previous history of deep venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolism (such as factor V Leiden deficiency), we commonly work with a hematologist to determine the proper postoperative anticoagulation program. In most circumstances, we start off with one of the injectable anticoagulants for the first several days to 2 weeks and then usually progress to an outpatient warfarin protocol, striving for an international normalized ratio (INR) of 1.5 to 2.0. A nurse monitors their coumadin dosage and INR levels. If there is any doubt whether a patient has a deep venous thrombosis due to postoperative calf pain or swelling, we ask that they go to the emergency room and undergo a venous duplex ultrasound of their lower extremities to rule out a deep venous thrombosis. To my knowledge, we have not had one of these to date with our prophylactic protocol, but if one is found, the patient would be appropriately treated with anticoagulation therapy to address the deep venous thrombosis or to have it closely monitored, if it is felt by the treating hematologist to be amenable to continued observation within the patient’s anticoagulation protocol. In addition to the concerns about previous surgical incisions for posterolateral corner reconstructions, retained hardware over the posterolateral corner of the knee can make it difficult, on occasion, to perform a surgical reconstruction. There are times when large 6.5-mm screws and washers are placed to perform a tenodesis-type procedure or a direct repair of all structures using a washer on the femur (Fig. 9-4). Similar hardware is sometimes placed into the fibula or even the tibia. Although we have not found the tibial hardware to be a particular problem in the identification of the normal attachment sites of these important posterolateral structures, the hardware that is in the femur or the fibula can be problematic at times.

Complications Associated with Posterolateral Knee Injuries

♦ Risk of Infection or Wound Breakdown

♦ Common Peroneal Nerve Injuries

♦ Deep Venous Thrombosis

♦ Previous Reconstructions and Retained Hardware

Complications Associated with Posterolateral Knee Injuries

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree