19

Complex Regional

Pain Syndrome Type 1

(Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy)

Carole W. Agin

History and Clinical Presentation

A 50-year-old woman was undergoing magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast. Intravenous access was started in her right antecubital fossa. As the infusion of gadolinium was started, the patient reported a burning pain in her arm from the antecubital fossa to her fingers. Her forearm and hand swelled. As the swelling increased, she reported numbness and cyanosis. Over the next few days the swelling resolved. Slowly sensation returned to her arm; however, the patient reported a constant burning pain. The patient also noted changes in the color of her hand and pain with movement of her wrist, elbow and shoulder.

PEARLS

- When presented with a questionable case of CRPS early after symptom development, a three-phase bone scan may be helpful.

- CRPS (RSD) is often a diagnosis of exclusion.

PITFALLS

- Radiologic studies performed late in the disease process may show changes secondary to disuse atrophy, which may be caused by other medical conditions.

- If the sympathetically maintained pain is the result of a persistent but treatable condition, the condition needs to be treated. Treating only the signs/symptoms of CRPS without addressing the underlying condition may prove futile.

- If the patient has a diagnosed psychiatric illness (i.e., post-traumatic stress disorder, depression), this must be treated or it can adversely affect any potential improvements obtained from other treatment modalities.

Diagnostic Studies

There are no radiologic findings that are pathognomonic for complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) type 1, reflex sympathetic dystrophy (RSD). Radiologic findings are often nonspecific, and many findings are a result of prolonged disuse, which is attributable to the pain associated with the syndrome. However, imaging studies can support a diagnosis of CRPS (RSD).

Fine detail radiography may help to suggest the presence of CRPS. Early radiologic changes seen with sympathetic hyperdysfunction include patchy demineralization of the epiphyses and short bones of the hands and feet. Periarticular osteoporosis in long bones and diffuse osteoporosis in small bones may be seen on plain radiographs. Subperiosteal resorption, striation, and tunneling of the cortex may occur. Comparison with the unaffected limb is always required. Unfortunately, these findings may be seen whenever there is disuse of a limb. As CRPS advances, patchy osteopenia may be seen.

Triple-phase scintigraphy has also been used to help diagnosis CRPS (RSD). Three-phase bone scanning measures the uptake of a radionucleotide tracer at three different times: arterial phase, measured seconds after the injection of tracer; soft tissue phase, measured after several minutes have passed; and mineral phase, measured hours after the tracer is given. The triple-phase bone scan pattern most consistently seen in a patient with CRPS (RSD) is that of increased flow to the involved extremity and delayed static images that show diffusely increased uptake activity throughout the involved extremity, usually in a periarticular distribution.

MRI studies may show skin thickening and tissue edema. Nuclear bone density measurements have been used to follow the progression of the syndrome.

Differential Diagnosis

Peripheral neuropathy disease

Inflammatory disease

Infectious disease

Vascular disease

Connective tissue disorder

Reflex sympathetic dystrophy

Diagnosis

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome, Type 1 (Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy)

The Committee on Taxonomy of the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) recently renamed reflex sympathetic dystrophy as complex regional pain syndrome type 1. This new taxonomy was promulgated in an attempt to establish uniform diagnostic criteria. This will aid in the development of treatment protocols for the syndrome. Previously many symptom constellations were included within the category of RSD, making treatment pathways and outcome studies difficult. A study done to evaluate the validity of the IASP’s CRPS diagnostic criteria to distinguish between CRPS and other neuropathies showed that the new classification did assist in improved accuracy of diagnosis.

To meet criteria for CRPS type 1 a patient must present with regional pain outside of the distribution of a single peripheral nerve and out of proportion to the inciting event. CRPS has been reported to develop after compression/crush injuries, lacerations, fractures, sprains, burns, or surgery. Allodynia and hyperalgesia are typically present. Abnormalities in skin blood flow (causing changes in skin temperature and color), abnormal sudomotor activity, and edema are also present. Dystonia and weakness, although not necessary for the diagnosis, may also be present. Trophic changes and personality changes may develop as the disease progresses.

CRPS type 2 has all of the same signs and symptoms; however, it follows injury of a major peripheral nerve.

Methods of Management

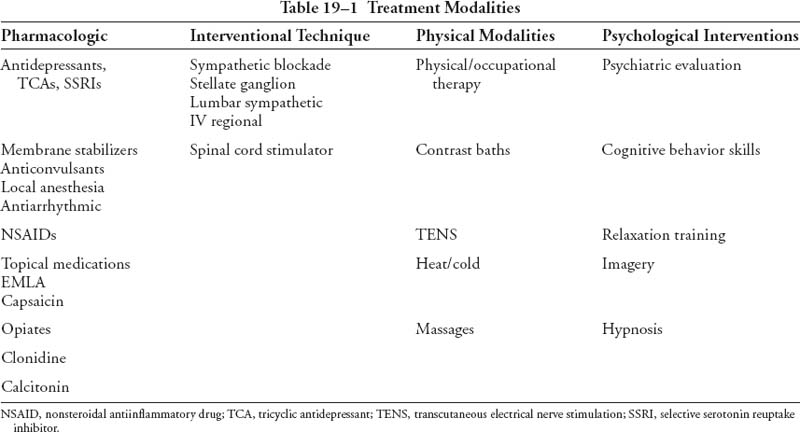

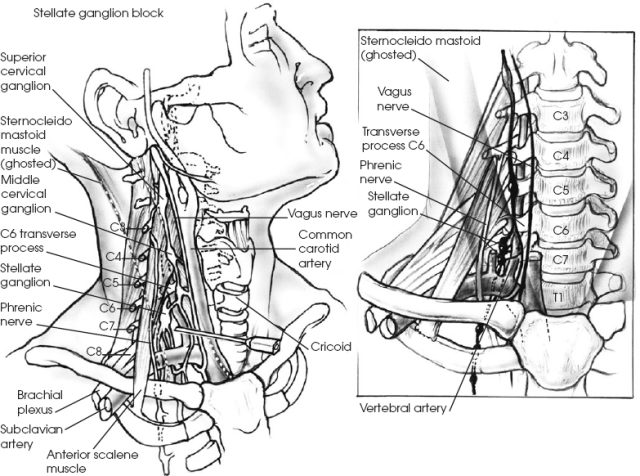

As the pathophysiology of CRPS type 1 (RSD) is not well understood, multiple treatment protocols have been described. The consensus is that these patients do best with a multidisciplinary treatment plan (Table 19–1). This includes regional blockade (Fig. 19–1), physical therapy, pharmacologic therapy, and psychological intervention. The earlier the syndrome is diagnosed and treatment is started, the better the chances for complete recovery.