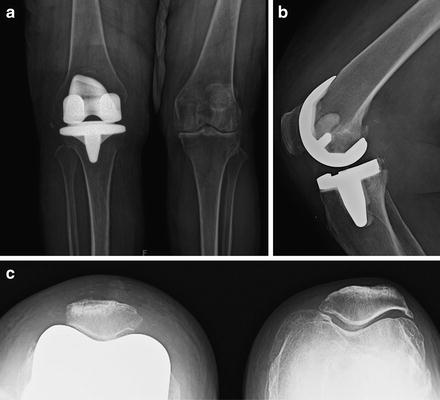

Fig. 2.1.

Preoperative X-rays of the knee. View: (a) anteroposterior, (b) lateral, (c) patellofemoral.

2.1.2 Management

The patient was diagnosed with end-stage osteoarthritis and, having failed conservative therapy, elected to undergo TKA. On the day of surgery, a medial parapatellar approach was used to access the joint. The distal femoral cut was made in 3° of valgus, and rotational alignment of the femoral component was set in reference to the anteroposterior axis and verified with the transepicondylar axis. The tibial cuts were made, and lateral release of the iliotibial band and the posterolateral capsule lateral to the popliteus tendon was performed to achieve appropriate flexion and extension gaps. Components were cemented in place, and the incision was closed. Shortly after the procedure was completed, the peroneal nerve was evaluated and found to be intact.

2.1.3 Outcome

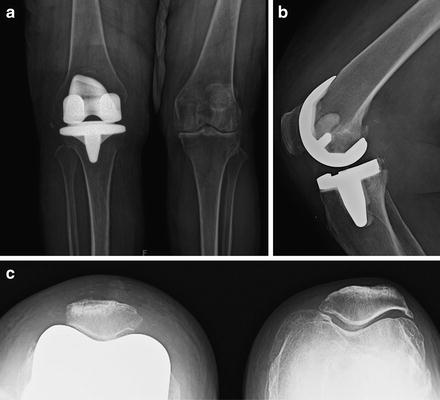

The patient returned to clinic 4 weeks postoperatively. She was doing well with her recovery. X-rays were obtained which showed femoral and tibial components well affixed and in near-anatomic alignment (see Fig. 2.2). Standing long-leg anteroposterior films from hip to knee were also obtained and showed the limb corrected to a neutral mechanical alignment (see Fig. 2.3). She was continued on physical therapy to improve strength and range of motion, and she followed up in clinic again 1 year postoperatively, at which point she was still doing well.

Fig. 2.2.

Postoperative X-rays of the knee. Views: (a) anteroposterior, (b) lateral, (c) patellofemoral.

Fig. 2.3.

Postoperative standing long-leg X-rays from hip to knee. Views: (a) anteroposterior, (b) lateral.

2.2 Literature Review

2.2.1 Introduction

Many surgeons consider total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in the valgus knee to be a more technically difficult procedure than TKA in the varus knee. The increased complexity is partly due to the complex soft tissue releases needed to help create a balanced knee and also partly due to the distal femoral deformity that is commonly encountered. Additionally, clinical decision-making can also be difficult in these cases, as there is no real consensus in the literature as to the best surgical approach and techniques to use, although several different methods have been proposed.

Of the various methods proposed in the literature, some of the main areas of discussion include (1) which surgical approach to use, (2) which method to use to properly align the components, (3) how to achieve a final, stable construct through balancing of soft tissues, and (4) selection of an implant with an appropriate degree of constraint. The intent of this chapter is to provide an overview of what has been proposed, helping guide a reader’s future study and thereby enabling him or her to make up his or her own mind on each matter.

2.2.2 Classification

Before broaching any of the aforementioned topics, it’s worth briefly reviewing the classification systems used for valgus knees (see Table 2.1). The most commonly referenced classification system in North America is probably the Krackow system [1], which categorizes valgus knees based on the integrity of the medial soft tissues and on prior surgeries. A slight variation of this system was described by Ranawat et al. [2] which also takes into consideration the tightness of the lateral soft tissues by assessing whether or not the deformity is fixed or correctable. Other classification systems also exist; however, further discussion of these will not be undertaken here, as most vary only slightly and rely on assessing the same variables: (1) degree of deformity, (2) ability to correct the deformity, (3) medial soft tissue integrity, and (4) history of prior osteotomy.

Type/variation | Krakow classification | Ranawat classification |

|---|---|---|

I | Valgus deformity secondary to bone loss in the lateral compartment and soft tissue contracture with medial soft tissue still intact | Minimal valgus deformity and minimal soft tissue stretching |

II | Like type I except for obvious attenuation of medial capsular ligament complex | Fixed valgus with more substantial deformity (>10 %) and with medial soft tissue stretching |

III | Severe deformity with valgus malpositioning of the proximal tibial joint line after overcorrected proximal tibial osteotomy | Severe osseous deformity after a prior osteotomy with an incompetent medial soft tissue sleeve |

2.2.3 Technical Aspects Particular to the Valgus Knee

2.2.3.1 Surgical Approach

Either a medial or a lateral approach can be used to access the knee when performing any TKA. The lateral approach is popular in Europe for valgus knees and has several proponents in the US literature [3, 4], although it has not been widely adopted here. The medial approach is more familiar to most surgeons in the United States and is thought to be adequate in all but cases with the most severe deformity.

The fact that it is familiar to most surgeons is one important benefit of choosing the medial approach. Another benefit is that, with this approach, the patella is easy to evert or translate, especially in valgus knees, providing good exposure to the joint without requiring any tibial tuberosity osteotomy. The major disadvantage to this approach is the difficulty of reaching lateral side of the joint in knees with severe valgus deformity, increasing the difficulty of the already somewhat complex lateral release needed to properly balance the knee. Additionally, using this approach risks devascularizing the patella if a too aggressive lateral release is performed and the lateral geniculate arteries are compromised.

The lateral approach has the benefit of direct access to the lateral side of the knee, where the deformity is, without risking the blood supply to the patella, but it is relatively more technically challenging. The main disadvantages to this approach are that (1) a tibial tuberosity osteotomy is often required in order to invert the patella and access the medial side of the knee due to the tuberosity’s slightly lateral location on the shaft of the tibia and (2) closure of the retinacular layer becomes problematic after correction of the deformity, necessitating more complex maneuvers such as a Z-cut capsulotomy to develop an adequate tissue layer for final closure.

2.2.3.2 Alignment

When performing any TKA, the main goals of the bony cuts should be to restore the knee joint to a neutral mechanical alignment and to ensure proper rotational alignment of the implants.

The mechanical axis of the leg is defined as the axis from the center of the femoral head to the center of the ankle, which ideally should pass directly through the center of the knee. In a neutrally aligned knee, the difference between the anatomical axis of the femur (defined by a line running down the center of the shaft of the femur) and this mechanical axis is commonly between 5 and 7°, depending upon the length of the patient’s femur. In valgus knees, however, the difference between these two axes is increased, and the mechanical axis runs lateral to the center of the knee. In varus knees, it is common for the distal femur to be cut at a valgus angle around 6° to obtain a cut that will be nearly perpendicular to the final mechanical axis of the leg following completion of the surgery. However, in valgus knees, some authors recommend using a smaller angle for the distal femoral cut [2]. This is done to minimally overcorrect for and thereby protect against recurrent valgus deformity, which is a fairly common complication following surgery in these patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree