54

Complex Fractures at the Base of the Thumb: Rolando Patterns

John A. Girotto, Shrika Sharma, and Thomas J. Graham

History and Clinical Presentation

The patient presents following an automobile accident with front end impact. At the time of the accident, the airbag deployed. Although the patient does not remember all the details, she thinks she put her hand up when the airbag deployed. She states her thumb is swollen and painful.

Physical Examination

The patient’s thumb is swollen with obvious deformity. The base of the thumb was tender to palpation. Palpation of the carpometacarpal (CMC) joint did not reveal a step-off, but passive movement of the thumb elicited pain. On examination, her left thumb had tenderness at the CMC joint, with a marked prominence of the first metacarpal base. Skin, two-point discrimination, and Allen’s test were intact.

Diagnostic Studies

Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs are obtained. They demonstrate the major fragments and the extent of the comminution (Fig. 54–1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans can be helpful in further defining the extent of the fracture if the radiographs are questionable.

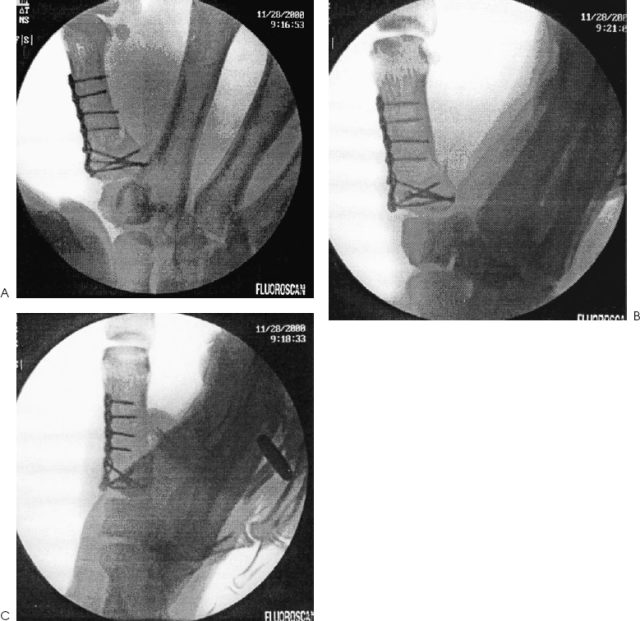

Figure 54–1. This patient sustained a closed, comminuted fracture of the thumb metacarpal base as the airbag of an automobile deployed on front-end impact. The anteroposterior (A) and lateral (B) radiographs demonstrate the major fragments and the extent of the comminution.

PEARLS

- Whenever possible, avoid the use of a transarticular wire that is to remain in after the metacarpal fixation.

PITFALLS

- The quality of reduction and the development of later arthritic changes and symptoms have been documented.

Differential Diagnosis

Bennett’s fracture

Metacarpal shaft fracture

Carpal fracture

Rolando’s fracture

Trapezium fractures

Thumb dislocation

Carpometacarpal joint osteoarthritis

Thumb sprain

Diagnosis

Rolando’s Fracture—Intraarticular Fracture of the Base of the Thumb

In 1910, Rolando described a Y-shaped fracture involving the base of the thumb metacarpal that does not result in the diaphyseal displacement characteristic of Bennett’s fracture pattern. Such comminuted intraarticular fractures of the base of the thumb metacarpal are usually in either a Y or a T configuration. Because of the likelihood of posttraumatic arthrosis after these fractures, accurate reduction is important.

In Rolando’s fractures, typically, the radial and ulnar fragments form a T- or Y-shaped pattern. The degree of comminution and the shape of the fragments dictate surgical management of these fractures. If the fragments appear large, exact reconstruction of the articular surface is advocated through an open approach similar to that utilized for Bennett’s fractures. Frequently, however, fractures are found to be more comminuted at the time of operative exploration than was suggested on radiograph.

The first CMC joint is a saddle joint responsible for movement in two axes: flexion/extension and adduction/abduction. Articular embarrassment due to axially loading or hyperextension can generate varying fracture patterns. Injuries to the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb are quite common and must be managed appropriately in this important digit. A stable metacarpophalangeal joint is critical for grip and dexterity.

Treatment recommendations for complex thumb base fractures have been varied. They have ranged from a nonoperative approach with aggressive early mobilization to open reduction and rigid internal fixation. As early as 1954, Gedda suggested that exact restoration of the CMC articular surface was necessary for optimal functional results.

When the comminution of the fracture prevents internal reduction and fixation, as in the more complex Rolando’s variants, many authors have advocated external fixation with or without tension band wiring. This technique maintains length and earlier motion. Kontakis et al reported their results with external fixation of Rolando’s fractures. Of 11 patients, only one had unacceptable results secondary to posttraumatic arthritis.

Treatment of the comminuted Rolando’s fracture remains controversial. Techniques have been described for open Kirschner-wire (K-wire) fixation of multiple fragments. Attempting to maximize reconstructed articular congruity, Langhoff and coworkers reviewed 17 patients with comminuted Rolando-type fractures and advocated the open placement of intrafragmentary K wires. Given the sample size, they were unable to demonstrate a relationship between the quality of reduction and the symptomatic occurrence of osteoarthritis. In fact, pinch and grip power was reduced by ∼20% on the affected side in nearly all patients. Similarly, 55% demonstrated osteoarthritis on radiographs. Following a small set of patients sustaining fractures of the first metacarpal base, Bartelmann et al also did not demonstrate a relationship between the quality of reduction and symptomatic outcomes. Radiographically, however, osteoarthritis was found to be lower with improved articular reduction.

Surgical Management

The surgical approach to the CMC joint of the thumb is similar to that described for the Bennett’s fracture. The Wagner incision allows good visualization, but can be slightly limiting in the ability to characterize and control the multifragmented Rolando’s fracture. A simple dorsal incision in which the tendon intervals (APL, extensor pollicis brevis, and extensor pollicis longus) are incised is not adequate to treat this injury.

Following the decision for operative intervention, the injured extremity is placed in a short-arm thumb spica splint. The surgery should be scheduled at the earliest time convenient for patient and surgeon. Anesthetic choices include either general or regional anesthetic, such as an axillary block. In preparation for the incision, a pneumatic tourniquet is applied and the arm is prepped with Betadine solution on a standard hand table. A first-generation cephalosporin is administered intravenously. A curvilinear Wagner type incision is planned along the first metacarpal to approach the CMC joint. This incision is placed slightly volar to the junction of the dorsal and palmar skin and curved volarly toward the wrist crease. Distally, the incision is kept to the volar side of the extensor pollicis brevis. Dorsal approaches offer inferior visualization of the basilar joint articular surfaces. The arm is then elevated and exsanguinated with an Ace wrap, and the tourniquet is inflated.

Under loupe magnification, the Wagner incision is made at the glabrous border of the thenar eminence. Hemostasis is achieved with the bipolar cautery. The distal branches of the radial sensory nerve and possible terminal branches of the palmar cutaneous nerve are identified and protected dorsally. The fascial attachments of the thenar musculature are identified and incised. This allows for ulnar elevation of the thenar muscles—the superficial abductor pollicis brevis and the opponens—while preserving the metacarpal periosteum to the greatest extent possible.

After the thenar eminence muscles are carefully dissected and reflected ulnarward, the capsule can be incised in a T fashion or longitudinally split. In our experience, the capsule likely has a rent or significant stripping, reflecting the magnitude of the forces that cause the Rolando’s fracture. The surgical reconstruction of the comminuted metacarpal base is intellectually and technically challenging. The surgeon must be facile with the osteology of this uniquely shaped joint. Often there is a relative deficit of bone due to either fragmentation of the thin cortex or impacted cancellous bone of the metaphysis. For these reasons, the following steps provide a systematic approach to the operative treatment of the Rolando’s fracture.

Assess the trapezial articular surface for injury. Remove any small fragments. Simplify the fracture by provisionally reducing the major articular fragments, and use K-wire fixation (0.035- or 0.045-inch) to stabilize the construct. An alternative may be to reduce the major shaft fragment back to the joint and volar fragment and then stabilize it with a transarticular wire. Apply primary fixation. This entails the application of a plate in most circumstances. The choices are a T plate or a condylar blade plate. The condylar blade plate is an excellent choice to rigidly fix the juxtaarticular fragments, but it is technically more difficult to use (Fig. 54–2). A mini-T plate may be slightly large for the thumb metacarpal, but would predictably stabilize the fracture.