Community Participation and the Environment: Theoretical, Assessment and Clinical Implications

Julie J. Keysor

Daniel K. White

INTRODUCTION

Mrs. X and Mrs. Y are both 62 years old. One year ago, both had right middle cerebral artery infractions with resultant left upper- and lower-extremity weakness and left-sided visual inattention. The hospital course for both included admission to an acute care hospital followed by a 3-week stay at an acute rehabilitation hospital. Both were discharged home with home services. Mrs. X and Mrs. Y have supportive spouses who live with them and have children who live nearby. Following their strokes, Mrs. X and Mrs. Y retired. Both are able to walk unlimited distances in the home and community settings with a standard cane, though both indicate they walk slower and shorter distances than before the stroke. Both have discontinued driving. Both have gross grip strength of the left upper extremity but are unable to perform fine motor activities. Active shoulder range of motion is about 30% in the left upper extremity.

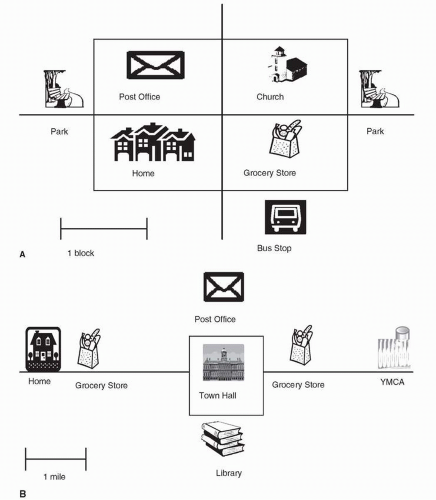

Mrs. X lives in a two-story townhouse in a highly populated urban area. A post office, grocery store, two community parks, the church she regularly attends, and a bus stop are located within five blocks of her home. There are ample level well-maintained sidewalks that are wide and well lit. Benches are scattered throughout the sidewalks, buses service the area frequently, and public transportation services for persons with disabilities are available. Mrs. X’s activities include visiting friends and family almost daily, volunteering to teach English classes at her church once a week, and participating in a book-of-the-month club that meets at her neighbor’s house, which she has just joined. When the weather is nice, she takes walks in the nearby park. Mrs. X has stopped grocery shopping since having her stroke and instead uses an online service that delivers the groceries to her home. Mrs. X generally gets around her community several times a week either by walking or by getting a ride with her friends and seems to have a fairly high degree of participation in her complex daily activities.

By contrast, Mrs. Y lives in a single level home in a suburban community. The town center is 2 miles away and contains a post office, library, and town hall with parking several hundred feet from the main entrances. Most of these buildings have stairs at the front entrance and a ramped access further from the stairs. There is a small grocery store a half mile from her home but they do not deliver groceries and a larger one 4 miles away. Before her stroke, she worked in the local school system and exercised at the local YMCA that was located 10 miles from her home. Most of her friends are scattered around town, particularly near the YMCA. The church Mrs. Y regularly attended prior to her stroke is 5 miles from her home.

Many of the sidewalks in Mrs. Y’s communities are uneven and are poorly maintained. A public transportation service does exist; however, the bus only comes twice a day. Many of the buildings have ramp access that is difficult to get to, stairs that have one railing, and limited parking. Mrs. Y has significantly curtailed her social activities since having her stroke, but she is still able to take care of the inside of her home. This includes vacuuming, preparing hot meals, and shopping for estate jewelry on e-bay. Mrs. Y was considering volunteering at a local bookstore in town; however, coordinating with her husband’s schedule proved to be too difficult. Mrs. Y is quite active in her home and often entertains friends and family in her home, but her community mobility is very limited and she has a rather low participation in her complex daily community activities (Fig. 18-1).

Despite the identical pathology, impairments, and functional limitations, the community participation levels of Mrs. X and Mrs. Y are very different. Mrs. X continued to participate in community activities; however, Mrs. Y did not. Medical providers are keenly aware of this paradox, but why does it exist? Is it even something that rehabilitation professionals should consider? If rehabilitation professionals should address this, how do we intervene to optimize community participation and the community-environment interaction? How do we assess the community-environment interaction?

This chapter reviews notions of how the environment impacts participation among adults with mobility limitations. We will discuss theoretical and conceptual frameworks linking the environment to participation, discuss methodological considerations regarding assessment of participation and the community environment, review the literature linking the community environment to participation among adults with mobility limitations, and, lastly, discuss several clinical

implications in this area of rehabilitation science. Our focus of this review is on the physical aspects of the environment. Elements of the social, political, attitudinal, or technological aspects of the environment are not reviewed in this chapter.

implications in this area of rehabilitation science. Our focus of this review is on the physical aspects of the environment. Elements of the social, political, attitudinal, or technological aspects of the environment are not reviewed in this chapter.

THEORETICAL AND CONCEPTUAL CONSIDERATIONS

Community Participation

“Participation” is a term used in the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) and is defined as “a person’s involvement in a life situation (1).” The concept of “life situation” pertains to areas in which people attain and define roles such as seeking and maintaining employment, seeking and securing an education, managing a household, and being a care provider. Nine domains are listed in the ICF that pertain to the activities and participations of people: learning and applying knowledge; general tasks and demands; communication; mobility; self-care; domestic life; interpersonal interactions and relationships; major life areas; and community, social, and civic life (1). Thus, the domain of participation addresses the extent to which and how people engage in complex day-to-day activities that comprise their daily lives. Fougeyrollas et al. (2) describe a similar concept “life habits” and define life habits as “daily activities

and social roles that ensure the survival and development of a person in society throughout his or her life.”

and social roles that ensure the survival and development of a person in society throughout his or her life.”

The term “participation” is similar to the terms handicap, defined as “a disadvantage for an individual that limits or prevents the fulfillment of a role that is normal for that individual (3),” and disability, defined as “restrictions in personal and social role behaviors (4, 5).” The concept that all these three terms are referring to encompasses the extent to which people engage in the complex daily activities that comprise the roles and activities of their daily lives. These broad role activities occur in the home and community setting. For the purposes of this chapter, however, we focus on community daily activities (community participation)—that is, activities that people do in their community when they leave their home—rather than on home activities.

Performance of complex daily activities is likely to be influenced by a multitude of factors. Managing one’s health, for example, entails scheduling an appointment during a time that is compatible for the patient, which is dependent upon the schedule and ability of the patient or his or her caregivers. A doctor’s visit entails securing transportation to the facility, which may entail public transportation, adaptive transportation, or the person driving himself or herself. Whether the patient takes public transportation or drives, he or she needs to navigate the physical premises of a parking garage and/or office building and arrive at the (correct) location of the appointment. Once at the correct location, the patient needs to navigate waiting rooms and small examining rooms, change clothing if necessary, may need to transfer onto equipment that is not adaptive, and pay for the service. Then, the patient needs to reverse all of these to get back to the origination point! “Going to the doctor’s office” thus comprises a number of activities including transferring, walking or propelling a wheelchair, driving or securing transportation, dressing, managing money or billing payment, and coordinating a calendar. These factors in turn are likely to be influenced by a person’s level of function, cognitive status, sensory systems and emotional status, the availability of social supports and other programs in the environment, and the presence of environmental obstacles or barriers that impede a patient’s ability to get to the doctor’s office.

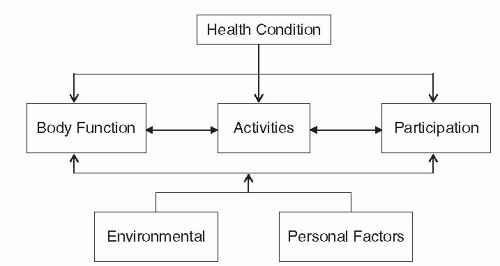

The ICF model provides a conceptual framework to examine the complex processes that are involved in the above example. Conceptually, the model proposes that participation is influenced by an individual’s body structure and function (defined as anatomical parts and physiological functions of organs and body systems) and his or her activity levels (defined as the execution of a task or action by the individual) (1). Other disablement theoretical models suggest similar relationships among body structures (impairments), functional activity (limitation in function), and performance of role behaviors (disability) (4, 5). Conceptual frameworks help clinicians and researchers organize the complicated array of factors that influence health and health problems.

The ICF, however, also functions as a structured classification system of health and disability outcomes. The ICF provides a detailed description of relevant items in body systems, functions, activities, and participation. Thus, items from assessment instruments can be “linked” to the respective ICF identifiers in respective domains. This type of classification system and linking strategy can be useful to clinicians and researchers. For clinicians, it can help guide the assessment of clinically relevant factors in various patient populations (including the selection of measurement instruments). For researchers, it can aid in understanding the conceptual underpinnings of instruments to guide selection of the best instrument for the factor of interest to study. Indeed, an extensive amount of research on developing and validating the ICF classification structure is currently underway, with rules for linking instruments to ICF classification categories developed and validated (6).

The example described previously in this section, however, does not solely entail elements of body systems, functions, activities, or participation. Rather, this scenario is likely to be influenced by factors outside the individual (e.g., the environment) as well as internal behavioral or motivational factors. Environmental and intra-individual behavioral and personal factors in the ICF framework are proposed to be contextual factors that modify the relationships among body systems, functions, activities, and participation (1) (Fig. 18-2). These factors represent the social and physical circumstances in which the person lives—that is, characteristics of the person (e.g., attitudes) or elements of the environment (1, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14). The role of the environment in disablement is also emphasized in the Institute of Medicine’s 1997 report that states a person’s involvement in life activities results from the interaction of the person within the environment in which the person exists. Limitations occur when the environment does not fit the individual (12, 13). Exactly how, however, would the environment impact participation among persons with functional limitations and disabilities? What are the important elements of the environment that need to be considered from a clinical perspective? To understand these questions, we need to understand the conceptual underpinnings of environmental assessment.

Conceptual Notions of the Environment-Participation Interaction

The environment may be viewed as everything external to the individual and is believed to have an impact on people’s behaviors and health outcomes. Researchers in the fields of

transportation and public health have shown that housing density, land use diversity, and street connectivity and design are related to how people navigate their community (15, 16, 17). People who live in environments with greater residential to commercial mixes have higher physical activity levels compared to those persons who live in environments that are more residential (18, 19, 20, 21). People who live closer to work establishments are more likely to walk to work, thereby having higher levels of physical activity (19). Generally, environments that are characterized as more “walkable” are associated with more physical activity patterns among their residents as compared to environments that are less “walkable” (20, 22). Research linking environmental factors to transportation and physical activity sheds some interesting perspectives into environment-participation research. Will these “global” factors of land use mix and street connectivity have a role in determining participation levels of people with functional limitations and disabilities?

transportation and public health have shown that housing density, land use diversity, and street connectivity and design are related to how people navigate their community (15, 16, 17). People who live in environments with greater residential to commercial mixes have higher physical activity levels compared to those persons who live in environments that are more residential (18, 19, 20, 21). People who live closer to work establishments are more likely to walk to work, thereby having higher levels of physical activity (19). Generally, environments that are characterized as more “walkable” are associated with more physical activity patterns among their residents as compared to environments that are less “walkable” (20, 22). Research linking environmental factors to transportation and physical activity sheds some interesting perspectives into environment-participation research. Will these “global” factors of land use mix and street connectivity have a role in determining participation levels of people with functional limitations and disabilities?

Participation in daily life activities is a much more complex phenomenon than engaging in physical activity or navigating one’s community. Which aspects of the environment impact participation? What are the characteristics of the environment-participation interaction? There are several conceptual frameworks in the field of rehabilitation that suggest answers to these questions. Fougeyrollas et al., in their early conceptual notions on how the environment was related to participation, defined “environment” as all facilitators and barriers external to the individual that influence participation (8). They suggested that the environment has different “levels” of influence: “micro personal,” “meso community,” and “macro societal” and identified four domains that were important for participation: (a) socioeconomic organization (e.g., family structure, political systems, and economic systems), (b) social roles (e.g., law, values, and attitudes), (c) nature (e.g., geography, climate, and time), and (d) development (e.g., architecture, land development, and technology) (8, 23).

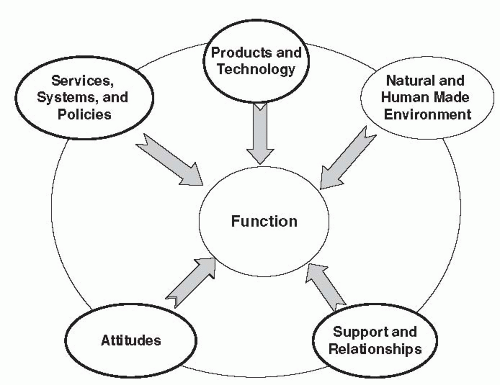

In the ICF, the “environment” is identified as a contextual factor that has positive and negative attributes that could either enhance or restrict ones’ level of involvement in life activities—that is, the environment is the “background” in which people’s life situations are embedded. The ICF organizes environmental factors into two levels: (a) individual and (b) societal. The individual level pertains to the immediate environment of the individual including settings such as home, workplace, and school. Physical and material features of the environment as well as direct contacts with people in the environment are included in this level. The societal level includes the formal and informal social structures, services, and overarching approaches or systems in the community or society that have an impact on individuals. Organizations and services related to work environment, community activities, government agencies, communication and transportation services, and informal social networks as well as laws, regulations, formal and informal rules, attitudes, and ideologies are included in this level. The ICF organizes environmental factors into five domains: (a) products and technology; (b) natural environment and human-made changes; (c) support and relationships; (d) attitudes; and (e) services, systems, and policies (1) (Fig. 18-3; Table 18-1).

FIGURE 18-3. Depiction of environment as a contextual factor in the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health. |

Assessment of each of the ICF environmental domains is evolving. While some researchers have developed approaches to assess the broad array of environmental factors (24), others have elaborated on physical aspects of the environment. Shumway-Cook et al. (25) developed a community environment assessment that identifies eight dimensions of the physical environmental domain: (a) temporal, (b) physical load, (c) terrain, (d) postural transitions, (e) distance, (f) density, (g) attentional demands, and (h) ambient conditions. Others ascertain the presence of community mobility barriers, mobility devices and technologies, and transportation facilitators (26).

It is not entirely clear which elements of the environment are relevant for rehabilitation considerations. It is clear, though, that the environment in which people live is complex and entails a number of factors that have elements that could impact the degree to which people with mobility limitations could be involved in their life activities, and it is likely these factors range from the factors that individuals directly interact with to societal and cultural factors.

Measurement Considerations

There are several methodological challenges to conducting and interpreting research on the links between the environment and participation. First, measurement of participation and environment is paramount to assessing the relationships between these complex phenomena. Researchers need valid and reliable measures of participation and the environment— with the assessments for each conducted in a manner that minimizes bias in the statistical relationships. The complexity of this, however, is substantial. Both participation and environment are complex domains, and assessing participation in terms of the environment in which people live is a complicated phenomenon.

TABLE 18.1 Description of Environmental Domains in the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Healtha | |

|---|---|

|