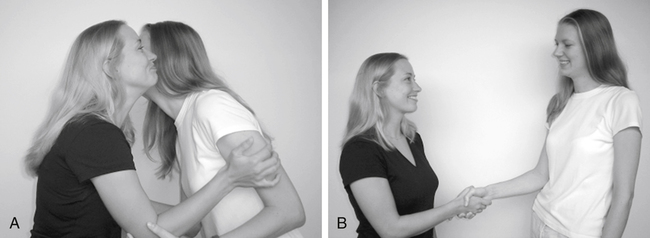

After reading this chapter, the reader will be able to: The American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) has defined a clear vision1 for the profession in the twenty-first century (Box 7-1). This has had an impact on goals and action in practice, education, and research as well as professional behaviors. Similar values and behaviors are recognized by the Section on Health Policy and Administration of APTA in the development of Leadership, Administration, Management, and Professionalism (LAMP) skills set forth by the Section.2 These skills are promoted in a LAMP document and annual LAMP Summit meeting. In the core values and beliefs of the 2002 LAMP Summit, all PTs, not just managers, must have LAMP skills to become effective professionals.2 A recent Delphi study by Lopopolo, Schafer, and Nosse3 revealed that the top-ranked LAMP skills identified by respondents were communication, professional involvement and ethical practice, delegation and supervision, stress management, reimbursement sources, time management, and health care industry scanning. All of the respondents were experienced managers and members of APTA who were familiar with the content of the LAMP skills. Of the top-ranked LAMP categories, communication had the highest median score and was therefore the most important category. The findings indicated that beginning PTs need “extensive knowledge” of communication techniques and should be “skilled” in applying these techniques in a clinical environment. These skills are essential in both the clinical management and the patient care aspects of physical therapy. To develop the knowledge and skill essential in communication, you need to appreciate what is involved in effective communication. As defined in Webster’s II New Collegiate Dictionary,4 communication is “the act or process of communicating; transmission. To communicate is to make known; to transmit to others; to have an interchange; as of ideas or information.” There are many types of communication skills, including skills in verbal and nonverbal interactions and reading, writing, and listening. Communication can occur between individuals, within an individual, or among a group of people. Communication may occur within an individual, and this is called internal dialogue.5 It is “heard” only by the individual himself or herself and may affect his or her nonverbal communication to other people. Internal dialogue may occur when the individual is alone, with another person, or in a group of people. Listening is a foundational communication skill for your success as a professional. Whether you are actively listening when interviewing a client or listening to a colleague request your input, your ability to listen actively will let the speaker know that you have understood his or her intended meaning. According to Davis,6 active listening requires practice and is not easy. It contains three elements: restatement, reflection, and clarification. Restatement involves repeating the words of the speaker as you have heard them. Reflection involves verbalizing both the content and the implied feelings of the sender. Clarification involves summarizing or simplifying the sender’s thoughts and feelings and resolving unclear verbalizations by the sender. As a physical therapy professional, you can develop skill with all five types of communication. You can benefit from understanding the impact of verbal and nonverbal communication on yourself, your colleagues, your patients, and their families. In addition, you can enhance your skills in reading, writing, and listening. According to Davis,6 communication by practitioners may enhance or detract from their therapeutic presence in their interactions. As a practitioner, you can learn the communication skills that enhance your therapeutic presence and thereby promote healing. The original research was conducted by use of a Delphi study with clinical educators from the University of Wisconsin in Madison. Clinical educators were asked to identify the behaviors essential for physical therapy professionals that were not explicitly part of the profession’s core of knowledge and technical skills but were required for success in the profession. Ten essential skills were identified. Each of these behaviors can be related to the development of effective communication skills. Through mastering each of these behaviors, you demonstrate the behaviors of a physical therapy professional and thereby enhance your communication with your clients, their families, and your colleagues.7 This research has recently been updated to address the changing scope of the physical therapy profession in response to increased autonomy and the new graduates from the Millennial generation (born 1980 to 2000). The 10 professional behaviors (formerly known as generic abilities) have remained the same as those identified in the original research; however, the rank order has changed, and they are now referred to as professional behaviors for the twenty-first century8 (see Boxes 7-2 and 7-3). These behaviors have also been recommended as essential for the development of LAMP skills for practicing clinicians.2 Three domains of learning have been described. The cognitive domain9 involves knowledge, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation, and deals with didactic learning. The psychomotor domain10 involves perception, guided response, complex overt response, and adaptation, and deals with “hands-on” skills. Skills in the affective domain are considered among the most difficult to teach because this domain deals with attitudes, values, and character development, which influence all the other professional skills.11 This also applies to communication skills. Communication falls within the affective domain. The mastery of affective behaviors develops over time. May and colleagues7 described beginning, developing, entry-level, and post–entry-level professional behaviors related to the generic abilities in their initial research. In the updated research, the 10 behaviors still have specific behaviors associated with performance at each level of development; however, the descriptors for the levels have changed to beginning, intermediate, entry-level, and post–entry-level behaviors. The current levels start with the beginning level, in which behaviors are consistent with those of a learner in the beginning of the professional phase of physical therapy education and before the first significant internship. This is followed by the intermediate level, in which behaviors are consistent with those of a learner after the first significant internship. The third level is entry level, in which the behaviors are consistent with those of a learner who has completed all didactic work and is able to independently manage a caseload with consultation as needed from clinical instructors (CIs), co-workers, and other health care professionals. The fourth level is post–entry level, in which the behaviors are consistent with those of an autonomous practitioner beyond entry level (see Box 7-3).8 Because many beginning PTs and PTAs are young adults, they are learning attitudes, behaviors, values, and character attributes that lay the foundation for their professional development.12 According to Davis,6 when students fail to acquire the behaviors on their own, faculty members should assist them in developing these behaviors. When students face challenges in the affective domain, faculty may assist them in learning professional behaviors through self-assessment using the generic abilities and guided discovery during advisory sessions with a faculty member.13 Faculty can also assist students in developing their affective communication skills by teaching them how to recognize and use rapport in their interactions. When building rapport, the professional must be aware of both verbal and nonverbal components of communication (Box 7-4).14 These are further described later. In verbal communication you can recognize a variety of communication patterns by listening to the speaker.14 The language patterns of the speaker may help you to identify his or her learning style. For example, a speaker may say “That sounds good” when hearing about the prescribed exercise program. This suggests an auditory learning pattern. Auditory learners may prefer to learn the exercises by hearing you describe how to perform them. The pace of the speaker might include long or short pauses between words or thoughts. The tonality of the speaker might be high pitched and nervous or low pitched and calm. The intent of the speaker might be to request help or demand service. The speed of the communication might be fast, slow, or variable. Through paying attention to these patterns, you can build rapport by matching the client’s verbal pace, tonality, intent, and speed. In nonverbal communication you can recognize the gestures, postures, haptics, proxemics, and oculesics of the speaker.14 Haptics involve the use of touch as part of a communication pattern. For some people, touching during speaking is an important cue. Others might consider touching to be rude. Proxemics is the distance between the speaker and the listener. Appropriate distance between speaker and listener varies depending on the cultural background of the speaker. Oculesics is the use of eye contact or gaze aversion. In some groups direct eye contact is a sign of respect for the speaker, whereas in other groups gaze aversion signals respect. As a professional you must learn the nonverbal cues that specifically apply to the patients you serve. Rapport is an important characteristic of communication. Rapport is defined as an interaction marked by mutual collaboration and respect but not necessarily indicating agreement.5 When people are in rapport, they have behavioral patterns that become similar in nature. The first of the three primary types of rapport is cultural rapport, which is established by using the form of dress or greeting appropriate to the setting. For example, you might wear a lab coat in an acute care clinical setting but a polo shirt and khaki pants in an outpatient orthopedic clinical setting. You might use a traditional greeting style appropriate for the culture of your patient, such as touching the patient’s cheek or shaking hands with the patient (Figure 7-1). The third type of rapport is behavioral. This is established when you mirror the posture and body movements of the person with whom you are speaking. You may also match the person’s voice tonality and tempo. For example, you might be working with a toddler in an early intervention program for your pediatric clinical rotation. You could squat or kneel at the eye level of the toddler to build behavioral rapport. Another example might be matching the posture while the person is sitting in a chair (Figure 7-2). To break rapport, you can mismatch the posture of the listener by not mirroring it (Figure 7-3).

Communication in Physical Therapy in the Twenty-First Century

Define the components of communication

Define the components of communication

Recognize the role of the affective domain in communication

Recognize the role of the affective domain in communication

Use rapport in building effective communication

Use rapport in building effective communication

Recognize effective communication in a multicultural health care environment

Recognize effective communication in a multicultural health care environment

Discuss high- and low-context communication assumptions

Discuss high- and low-context communication assumptions

Recognize the culture of medicine

Recognize the culture of medicine

Discuss differences in communication across generations

Discuss differences in communication across generations

Recognize differences in religious, spiritual, agnostic, and atheistic orientations

Recognize differences in religious, spiritual, agnostic, and atheistic orientations

Respond effectively to patients/clients with visual or auditory impairments or both

Respond effectively to patients/clients with visual or auditory impairments or both

Respond effectively to patients/clients and their caregivers and families

Respond effectively to patients/clients and their caregivers and families

Respond effectively with other members of the health care team

Respond effectively with other members of the health care team

Develop effective communication as a student in both the classroom and the clinic

Develop effective communication as a student in both the classroom and the clinic

Recognize the role of digital communication in education and health care

Recognize the role of digital communication in education and health care

What Is Communication?

Verbal and Nonverbal Communication

Listening

Professional Behaviors (Formerly Known as Generic Abilities) and Communication

Building Affective Communication Skills

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Musculoskeletal Key

Fastest Musculoskeletal Insight Engine