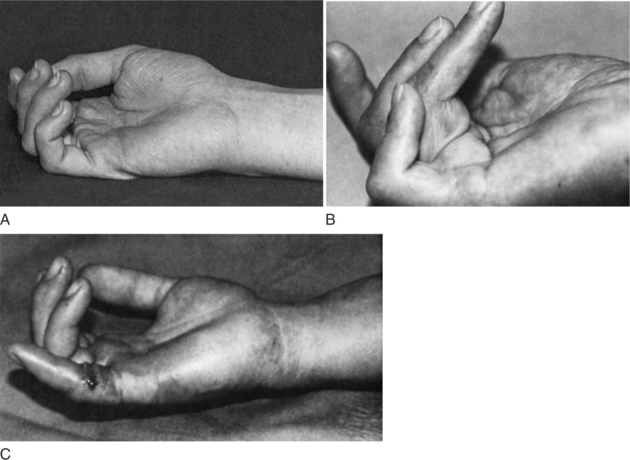

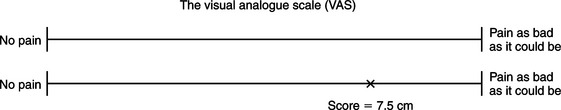

CHAPTER 5 1 List components of a clinical examination for splinting. 2 Describe components of a history, an observation, and palpation. 3 Describe the resting hand posture. 4 Relate how skin, vein, bone, joint, muscle, tendon, and nerve assessments are relevant to splinting. 5 Identify specific assessments that can be used in a clinical examination before splinting. 6 Explain the three phases of wound healing. 7 Recognize the identifying signs of abnormal illness behavior. 8 Explain how a therapist can assess a person’s knowledge of splint precautions and wear and care instructions. Time-efficient informal assessments may indicate the level of hand function initially and the results may prompt the therapist to select more sophisticated testing procedures, as indicated by the person’s condition [Fess 1995]. Generally, initial and discharge evaluations are most comprehensive in scope, whereas regular reassessments are usually more focused. The assessment process for the upper extremity should incorporate data from an interview, observation, palpation, and a selection of tests that are objective, valid, and reliable. Form 5-1 is a check-off sheet therapists can use when evaluating a person with upper extremity dysfunction. Beginning with a medical history, the therapist gathers data from various sources. Depending on the setting, the therapist may have access to the person’s medical chart, surgical or radiologic reports, and the physician’s referral or prescription. The person’s age, gender, and diagnosis are typically easy to obtain from these sources. Client age is important because some congenital anomalies and diagnoses are unique to certain age groups. Age may also affect prognosis or length of recovery. Some problems are unique to gender. Therapists ask about general health as well as about any prior orthopedic, neurologic, psychologic, or cardiopulmonary conditions [Ellem 1995]. Habits and conditions such as smoking [Mosely and Finseth 1977, Siana et al. 1989], stress [Ebrecht et al. 2004], obesity [Wilson and Clark 2004], and depression [Tarrier et al. 2005] may influence rehabilitation [Ramadan 1997]. The therapist asks the client about any previous upper extremity conditions and their dates of onset in order to assess the current condition. The therapist inquires about any prior treatments and their results. The therapist can determine clients’ insight into their condition by asking them to describe what they understand about their condition. Observations are noted immediately when the person walks into a clinic or during the first meeting between the therapist and client. For example, the therapist should observe how the person carries the upper extremity, looking for reduced reciprocal arm swing, guarding postures, and involuntary movements such as tremors or tics [Smith and Bruner 1998]. For example, facial tics may be a sign of a neurologic or psychological problem. Further information is gleaned from observing facial movements, speech patterns, and affect. For example, if there is a facial droop the therapist may suspect that the client has Bell’s palsy or has had a stroke. In addition, the therapist should always observe whether the person is able to answer questions and follow instructions. A general inspection of the person’s upper quarter (including the neck, shoulder, elbow, forearm, wrist, and hand) is completed, and joint attitude is noted. The therapist notes the posture of the affected extremity and looks for any postural asymmetry and guarded or protective positioning. A normal hand at rest assumes a posture of 10 to 20 degrees of wrist extension, 10 degrees of ulnar deviation, slight flexion and abduction of the thumb, and approximately 15 to 20 degrees of flexion of the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints. The fingers in a resting posture exhibit a greater composite flexion to the radial side of the hand (scaphoid bone), as shown inFigure 5-1 [Aulicino and DuPuy 1990]. The thumbnail usually lies perpendicular to the index finger. These hand postures are a useful basis for splint fabrication because a person’s hand often deviates from the normal resting posture when injury or disease is present. A variety of presentations can be observed by the therapist and will contribute to the overall clinical picture of the person. The following are noteworthy observational points [Ellem 1995]. • Position of hand in relationship to the body: protective or guarding posture • Diminished or absent reciprocal arm swing • Finger pads: thin or smooth (loss of rugal folds, fingerprint lines) • Lesions: scars, abrasions, burns, wounds • Heberden’s or Bouchard’s nodes • Neurologic deficit postures: claw hand, wrist drop, monkey hand • External devices: percutaneous pins, external fixator, splints, slings, braces • Deformities: boutonniere, mallet finger, intrinsic minus hand, swan neck • Pilomotor signs: appearance of “goose pimples” or hair standing on end After a general inspection of the client, palpation of the affected areas is completed when appropriate. A therapist palpates any area in which the person describes symptoms, including any area that is swollen or abnormal [Smith and Bruner 1998]. Muscle bulk is palpated on each extremity to compare proximal and distal muscles, as well as to compare right and left. Muscle tone is best assessed through passive range of motion (PROM). When assessing tone, the therapist should coach the client to relax the muscles so that the most accurate results can be obtained. The client’s skin should be examined by the therapist. In the presence of ulcers, gangrene, inflammation, or neural or vascular impairment, skin temperature may change and can be felt during palpation [Ramadan 1997]. In the presence of infection, draining wounds, or sutured sites, therapists wear sterile gloves and follow universal precautions. Assessment selection is a critical step in formulating appropriate treatment interventions. There are more than 100 assessments in the musculoskeletal literature [Suk et al. 2005]. Several factors must be considered in selecting an assessment, including content, methodology, and clinical utility [Suk et al. 2005]. In order to critically choose assessment tools used for practice, one must understand the psychometric development of such tools. Content of an assessment is what the tool is attempting to measure. Content can be separated into three categories: type, scale, and interpretation. The type of content can be focused on data gathered by the clinician or data reported by the client. The scale of the content refers to the measurements or questions that constitute the tool and how they are measured. Content interpretation addresses how scores or measures pertain to “excellent” or “poor” outcomes [Suk et al. 2005]. Methodology of the tool relates to validity, reliability, and responsiveness. Validity is the extent to which the assessment measures what it intends to measure.Table 5-1 lists and defines the various types of validity. Reliability is the consistency of the assessment.Table 5-2 lists and defines the types of reliability. Responsiveness refers to the assessment’s sensitivity to measure differences in status [Suk et al. 2005]. Table 5-1 Definitions of Types of Validity Table 5-2 Definitions of Types of Reliability Clinical utility refers to the degree the tool is easy to administer by the therapist and the degree of ease the client experiences in completing the assessment. Utility is a subjective component addressing the degree to which the tool is acceptable to the client and the degree to which the tool is feasible to the therapist. Factors that impact clinical utility include training on administration, cost and administration, documentation, and interpretation time [Suk et al. 2005]. Assessment tools can be categorized in several ways. There are standardized and nonstandardized assessment tools. Some assessments are norm based, whereas others are criterion based. Bear-Lehman and Abreu [1989] suggest that evaluation is a quantitative and qualitative process. Thus, therapists who select assessments that produce precise, objective, and quantitative measurement decrease subjective judgments and increase their ability to obtain reproducible findings. However, therapists are cautioned to reject the tendency to neglect important information about their clients that may not be quantifiable [Bear-Lehman and Abreu 1989]. Qualitative information—such as attitude, pain response, coping mechanisms, and locus of control (center of responsibility for one’s behavior)—influence the evaluation process. “The selection of the hand assessment tools to be used, the art of human interaction between the therapist and the client, the art of evaluating the client’s hand as a part, but also as an integrated whole, are part of the subjective processes involved in hand assessment” [Bear-Lehman and Abreu 1989, p. 1025]. Even objective evaluation tools require the comprehension and motivation of the client. Unfortunately, there is no universally accepted upper extremity assessment tool. Depending on the setting, a battery of assessments may be developed by the facility or department. In other settings, therapists use their clinical reasoning to determine what battery of assessments will be used with each person. Therapists should keep in mind that a theoretical perspective as well as a diagnostic population can influence the evaluation selection [Bear-Lehman and Abreu 1989]. For example, one facility’s assessment reflects a biomechanical perspective whereas another facility’s assessment reflects a neurodevelopmental perspective. The therapist has several options for evaluating pain, including interview questions, rating scales, body diagrams, and questionnaires.Box 5-1 lists questions a therapist can ask the person in relationship to pain [Fedorczyk and Michlovitz 1995]. Therapists often use a combination of pain measures to obtain an accurate representation of the client’s pain [Kahl and Cleland 2005]. The Verbal Analog Scale (VeAS) can be used to determine the person’s perception of pain intensity. The person is asked to rate pain on a scale from 0 to 10 (0 refers to no pain and 10 refers to the worst pain ever experienced). Reliability scores for retesting under the VeAS are moderate to high, ranging from 0.67 to 0.96 [Good et al. 2001, Finch et al. 2002]. When correlated with the Visual Analog Scale (ViAS), the VeAS had a reliability score of 0.79 to 0.95 [Good et al. 2001, Finch et al. 2002]. Finch et al. [2002] reported that a three-point change in score is necessary to establish a true pain intensity change. Thus, the VeAS may be limited in detecting small changes, and clients with cognitive deficits may have trouble following instructions to complete the VeAS [Flaherty 1996, Finch et al. 2002]. A ViAS can also be used to rate pain intensity. A person is asked to look at a 10-cm horizontal line. The left side of the line represents “no pain” and the right side represents “pain as bad as it could be.” The person indicates pain level by marking a slash on the line, which represents the pain experienced. The distance from no pain to the slash is measured and recorded in centimeters (Figure 5-2). The ViAS “may have a high failure rate because patients may have difficulty interpreting the instructions” [Weiss and Falkenstein 2005, p. 63]. Errors can occur due to changes in length of the line resulting from photocopying [Kahl and Cleland 2005]. Both VeAS and ViAS are unidimensional assessments of pain (i.e., intensity) [Kahl and Cleland 2005]. Although test-retest is not applicable to self-reported measures, studies have demonstrated a high range of test-retest reliability (ICC = 0.71 to 0.99) [Enebo 1998, Good et al. 2001, Finch et al. 2002]. When compared to the VaAS, concurrent validity measures ranged from 0.71 to 0.78 [Enebo 1998]. A body diagram consists of outlines of a body with front and back views, as shown inFigure 5-3. The person is asked to shade or color in the location of pain that corresponds to the body part experiencing pain. Colored pencils corresponding to a legend can be used to represent different intensities or types of pain, such as numbness, pins and needles, burning, aching, throbbing, and superficial.

Clinical Examination for Splinting

Clinical Examination

History

Interview

Observation

Palpation

Assessments

TYPE OF VALIDITY

DEFINITION

Construct validity

The degree to which a theoretical construct is measured by the tool

Content validity

The degree to which the items in a tool reflect the content domain being measured

Face validity

Determination if a tool appears to be measuring what it is intended to measure

Criterion validity

The degree to which a tool correlates with a “gold standard” or criterion test (it can be assessed as concurrent or predictive validity)

Concurrent validity

The degree to which the scores from a tool correlate with a criterion test when both tools are administered relatively at the same time

Predictive validity

The degree to which a measure will be a valid predictor of a future performance

TYPE OF RELIABILITY

DEFINITION

Inter-rater reliability

The degree to which two raters can obtain the same ratings for a given variable

Test/retest reliability

The degree to which a test is stable based on repeated administrations of the test to the same individuals over a specified time interval

Internal consistency

The degree to which each item of a test measures the same trait

Intra-rater reliability

The degree to which one rater can reproduce the same score in administering the tool on multiple occasions to the same individual

Pain

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Clinical Examination for Splinting