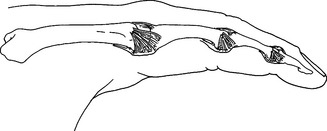

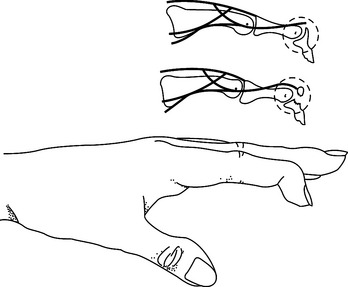

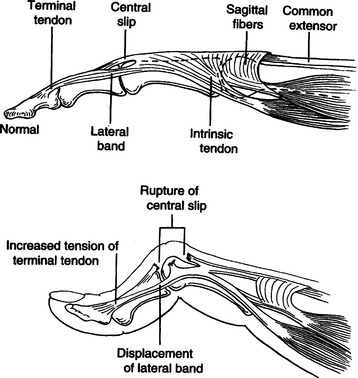

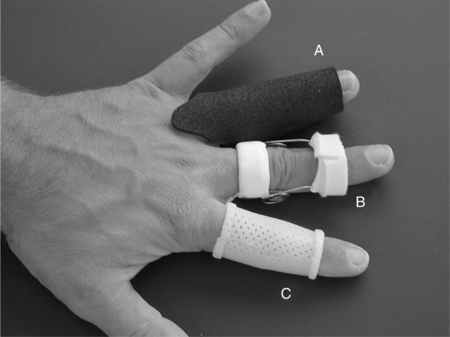

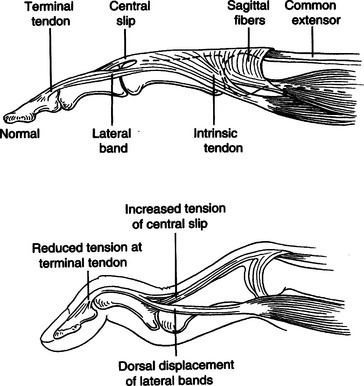

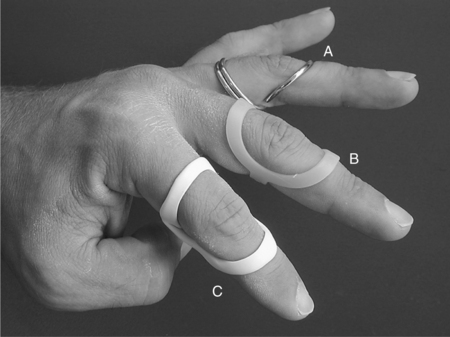

CHAPTER 12 1 Explain the functional and anatomic considerations for splinting the fingers. 2 Identify diagnostic indications for splinting the fingers. 4 Describe a boutonniere deformity. 5 Describe a swan-neck deformity. 6 Name three structures that provide support to the stability of the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint. 7 Explain what buddy straps are. 8 Apply clinical reasoning to evaluate finger splints in terms of materials used, strapping type and placement, and fit. 9 Discuss the process of making a mallet splint, a gutter splint, and a PIP hyperextension block splint. The PIP and DIP joints are hinge joints. These joints have collateral ligaments on each side that provide joint stability and restraint against deviation forces. The radial collateral ligament protects against ulnar deviation forces, and the ulnar collateral ligament protects against radial deviation forces. On the palmar (or volar) surface is the volar plate, which is a fibrocartilaginous structure that prevents hyperextension. The central extensor tendon crosses the PIP joint dorsally and is part of the PIP joint dorsal capsule. It is implicated in boutonniere deformities. The lateral bands, which are contributions from the intrinsic muscles, and the transverse retinacular ligament are additional structures that contribute to the delicate balance of the extensor mechanism at the PIP joint. They are implicated in boutonniere deformities and swan-neck deformities. The terminal extensor tendon attaches to the distal phalanx and is implicated in mallet finger injuries (Figure 12-1) [Campbell and Wilson 2002]. For any finger problem, it is always important to prioritize edema control. Treatment for edema can often be incorporated into the splinting process. Examples of this would be the use of self-adherent compressive wrap under the splint or to secure the splint on the finger. For diagnoses that require splint use 24 hours per day but permit washing of the digit, it may be appropriate to fabricate one splint for shower use and another for use during the rest of the day. In general, thinner LTT is typically used on digits because it is less bulky yet strong enough to support or protect these relatively small body parts. On a stronger person or a person with larger hands, 3/32-inch material may be better to use than 1/16-inch thickness. Selecting perforated versus nonperforated splinting material is partly a matter of personal choice, but use caution with perforated materials because the edges may be rougher and there can be the possibility of increased skin problems or irregular pressure—particularly if there is edema. Smaller perforations seen in microperforated materials minimize the risk. A mallet finger presents as a digit with a droop of the DIP joint (Figure 12-2). This posture often occurs as a result of axial loading with the DIP extended or flexion force to the fingertip. The terminal tendon is avulsed, causing a droop of the DIP. A laceration to the terminal tendon may also cause this problem [Hofmeister et al. 2003]. The DIP joint should be splinted for about 6 weeks to allow the terminal tendon to heal. This terminal tendon is a very delicate structure, and for this reason the joint should not be left unsupported or be allowed to flex for even a moment during this 6-week interval. It can be challenging to achieve this continuous DIP support because there is also the need for skin care and air flow. Practice with the client so that there is good understanding of techniques to support the DIP joint while performing skin hygiene and when applying and removing the splint [Cooper 2007]. After about 6 weeks of continual splinting and with medical clearance, the client is weaned off the splint. It is usually still worn at night for several weeks. At this time, it is very important to watch for the development of a DIP extensor lag. If this is noticed, resume use of the splint and consult the physician. A boutonniere deformity is a finger that postures with PIP flexion and DIP hyperextension (Figure 12-3). This deformity can result from axial loading, tendon laceration, burns, or arthritis. The central extensor tendon (also called the central slip) is disrupted, which leads to the imbalance of the extensor mechanism as the lateral bands displace volarly. If not treated in a timely manner, the PIP joint extensor lag may become a flexion contracture. In addition, the DIP joint may lose flexion motion due to tightness of the oblique retinacular ligament (ORL), also called the ligament of Landsmeer. The goal of splinting for boutonniere deformity is to maintain PIP joint extension while keeping the MCP and DIP joints free for about 6 to 8 weeks. If there is a PIP flexion contracture, a prefabricated dynamic three-point extension splint might be used—or a static splint can be adjusted serially with the goal of achieving full passive PIP extension. There are various types of splints for boutonniere deformity, including simple volar gutter splints.Figure 12-4 depicts some common options for splinting the PIP joint in extension while keeping the DIP joint free. In some cases, including the DIP joint in the splint may be preferable because this will increase the mechanical advantage. It is usually acceptable to do this if the ORL is not tight. Serial casting is also an option with this diagnosis (Figure 12-5). This technique requires training and practice before being used on clients [Bell-Krotoski 2002, 2005]. After 6 to 8 weeks of splinting and with medical clearance, the client is weaned off the splint. At this time, it is important to watch for loss of PIP extension. If this is noted, adjust splint usage accordingly. A swan-neck deformity is seen when the finger postures with PIP hyperextension and DIP flexion (Figure 12-6). Positionally, the swan-neck deformity at the PIP and DIP is the opposite of the boutonniere deformity. It may be possible to correct the PIP and DIP joints passively—or they may be fixed in their deformity positions. There are multiple possible causes of this deformity that may occur at the level of the MCP, the PIP, or the DIP joints. As with boutonniere deformity, the result is an imbalance of the extensor mechanism—but with a swan-neck deformity the lateral bands displace dorsally. In addition to other traumatic causes, it is not uncommon for people with rheumatoid arthritis to demonstrate swan-neck deformities [Alter et al. 2002, Deshaies 2006]. The goal of splinting for swan-neck deformity is to prevent PIP hyperextension and to promote DIP extension while not restricting PIP flexion. A dorsal gutter with the PIP joint in slight flexion (about 20 degrees) can be made. If the DIP demonstrates an extensor lag, the splint can cross the DIP and a strap can be added to support the DIP in neutral. Less restrictive styles of splints are shown inFigure 12-7. These are three-point splints that prevent PIP hyperextension but allow PIP flexion. They can be either custom formed or prefabricated. PIP sprains are graded in terms of severity, from grade I to grade III.Box 12-1 describes these grades and identifies proper treatment. PIP joint dislocations are also described in terms of the direction of joint dislocation (i.e., dorsal, lateral, or volar). PIP joint sprains are associated with fusiform swelling, which is fullness at the PIP joint and proximal and distal tapering. Edema control is critical with this diagnosis. The goal of splinting finger PIP sprains is to support the PIP joint and promote healing and stability. Splinting options for the injured PIP joint with extension limitations are similar to those used for boutonniere deformities. If there is a PIP flexion contracture, dynamic or serial static PIP extension splinting is used—or serial casting may be considered. If there has been a volar plate injury, a dorsal gutter is fabricated to block about 20 to 30 degrees of PIP extension while allowing PIP flexion (Figure 12-8).

Splinting for the Fingers

Functional and Anatomic Considerations for Splinting the Fingers

Diagnostic Indications

Mallet Finger

Splinting for Mallet Finger

Boutonniere Deformity

Splinting for Boutonniere Deformity

Swan-neck Deformity

Splinting for Swan-neck Deformity

Finger PIP Sprains

Splinting for Finger PIP Sprains

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Splinting for the Fingers