OVERVIEW

Physical medicine and rehabilitation focuses on the restoration of function and the subsequent reintegration of the patient into the community. As with other branches of medicine, the cornerstone of physical medicine and rehabilitation is a meticulous and thorough clinical evaluation of the patient. Therapeutic intervention by physiatrists must be based on proper assessment of the patient. Impaired function cannot be isolated from preexisting and concurrent medical problems or from the social circumstances of the individual patient.

Evaluation of Function

Medical diagnosis focuses on the historical clues and physical findings that lead the examiner to the correct identification of disease. After a medical diagnosis is established, the physiatrist must ascertain functional consequences of the disease. Appropriate clinical evaluation requires the examiner to have a clear understanding of the distinctions among the disease, body functions, activity limitations, and participation restrictions, as discussed in

Chapter 19.

If a disease cannot be eliminated or its severity cannot be reduced through medical or surgical means, measures are used to minimize its impact on functioning. For example, a weak muscle can be strengthened or a hearing impairment can be minimized with the use of an electronic aid. When disease process that leads to impaired functioning cannot be eliminated or its severity cannot be reduced, physiatric intervention must address the limitations on activity and the restrictions on participation. For successful rehabilitation, the physiatrist not only must address the consequences of impaired functioning directly but also must identify intact functional capabilities. When intact capabilities and their use are augmented and adapted to new uses, functional independence can be enhanced.

Case 1

AW had gained much enjoyment and self-esteem as a competitive runner before a spinal cord injury that left him with paraplegia. During and after inpatient rehabilitation, he vigorously pursued a cardiovascular and upper extremity conditioning program. He obtained an ultralightweight sport wheelchair and resumed competitive athletics as a wheelchair racer, winning several regional races.

Comment: AW’s intact capabilities included normal arm strength, a competitive spirit, and self-discipline. Through augmentation and adaptation and with the use of an appropriate wheelchair, he regained enjoyment and self-esteem in his athletic endeavors.

Sometimes it is not possible to ascertain the specific disease responsible for a patient’s constellation of historical, physical, and laboratory findings. Medical management must then address the symptoms of the patient. Although diagnosis is highly desirable, it is not a prerequisite to the identification and subsequent management of functional loss. To determine the expectations of future activity in relation to past activity, the physiatrist should attempt to characterize the temporal nature of the disease process over time.

Case 2

FZ, a 62-year-old woman, had difficulty climbing stairs. When questioned, she revealed that she and her husband had been in the habit of taking a 30-minute evening walk for many years. However, 2 years earlier, fatigue began to limit her walk to no more than a few blocks. During the previous year, she had had difficulty rising from low seating, and 6 months previously, she reluctantly quit taking walks. During the preceding few weeks, she had found that climbing stairs was a burden, and she had started taking showers because she needed assistance getting out of the bathtub.

FZ reported no sensory deficits. Physical examination showed hypotonic muscle stretch reflexes and predominantly proximal muscle weakness. Electrodiagnostic studies and muscle biopsy demonstrated a noninflammatory myopathy; however, further extensive evaluation failed to determine a cause. FZ was provided with a bath bench, a toilet seat riser, a lightweight folding wheelchair for long-distance mobility, and a cane for short distances. She was instructed in safe ambulation with the cane, operation of the wheelchair, energy conservation techniques, and the proper placement of bathroom safety bars. Safe automobile operation was documented, and she was provided with documentation to obtain a handicapped parking permit. The functional impact of potentially progressive muscle weakness was discussed with her, and she was given supportive counseling.

When FZ returned for a follow-up examination 1 month later, muscle testing showed only a slight progression of her weakness, and her functional capabilities were unchanged. Another follow-up examination was scheduled for 6 weeks later.

Comment: Although a specific diagnosis was not established, rehabilitation intervention addressed the patient’s specific functional losses. Serial evaluations at regular follow-up intervals allowed the physiatrist to identify and minimize future functional loss.

Comprehensiveness of Evaluation

The scope of physical medicine and rehabilitation encompasses more than a single organ system. Attention to the whole person is paramount. The objective of the physiatrist is to eliminate disability and restore functioning. The goal is to empower the individual to attain the fullest possible physical, mental, social, and economic independence by maximizing activity and participation. Consequently, the evaluation must assess not only the disease but also the way the disease affects and is affected by the person’s family and social environment, vocational responsibilities and economic state, avocational interests, hopes, and dreams.

Cases 3 and 4

CC, a 63-year-old piano tuner, had a left cerebral infarction manifested only as minimal dysfunction of the dominant right hand. Despite demonstrating discrete function of the digits of the involved hand on physical examination, he was psychologically devastated to find that he could no longer accomplish the fine and precise motor patterns necessary to continue in his profession.

BD, a 63-year-old corporate attorney, had a left cerebral infarction resulting in severe spastic weakness of his nondominant upper extremity. He completed some paperwork every day during his inpatient rehabilitation and returned to full-time employment shortly after finishing treatment.

Comment: For each person, the degree of functional impairment is uniquely and disproportionately related to the extent of resultant limitations in activity and restrictions in participation.

Interdisciplinary Nature of Evaluation

Although most of this chapter addresses the patient history and physical examination as related to the rehabilitation evaluation, these are only part of the comprehensive rehabilitation assessment. This statement is not meant to deprecate the usefulness of these traditional tools for the physician. Both are of critical importance and serve as the basis for further evaluation; yet, by their very nature, they are also limited. Speech and language disorders can inhibit communication. Subjective interpretation of the facts by the patient and the family can cloud the objective assessment of function. Performance cannot be optimally assessed by interview and physical examination alone.

For example, asking the patient about ambulation skills during the interview may identify a potential problem, but such skills can only be assessed objectively and reliably by having the physician and physical therapist observe the patient’s ambulation in various situations. Likewise, the occupational therapist must assess the performance of activities of daily living, and the rehabilitation nurse must assess the safety and judgment of the hospitalized patient. The speech therapist furnishes a measured assessment of language function and, through special communication skills, may obtain information from the patient that was missed during the interview. The rehabilitation psychologist provides a quantified and standardized assessment of cognitive and perceptual function and a skilled assessment of the patient’s current psychological state. Through interaction with the patient’s family and employer, the social worker can provide useful information that is otherwise unavailable regarding the patient’s social support system and economic resources. The concept of the physical medicine and rehabilitation team applies not only to evaluation of the patient but also to ongoing management of the rehabilitation process in the outpatient as well as the inpatient practice setting.

PATIENT HISTORY

Ordinarily, the patient history is obtained in an interview of the patient by the physiatrist. If communication disorders and cognitive deficits are encountered during the evaluation, additional corroborative information must be obtained from significant others accompanying the patient. The spouse and family members can be valuable resources. The physiatrist may also find it necessary to interview other caregivers, such as paid attendants, public health nurses, and home health agency aides.

The major components of the patient history are the chief report of symptoms, the history of the present illness, the functional history, the past medical history, a review of systems, the patient profile, and the family history.

Chief Report of Symptoms

The goal in assessing the chief report of symptoms is to document the patient’s primary concern in his or her own words. Patients often report an impairment in the form of a symptom that may suggest a certain disease or group of diseases. A report of “chest pain when I walk up a flight of stairs” suggests cardiac disease, whereas a report that “my hands ache and go numb when I drive” hints at carpal tunnel syndrome.

Of equal importance is the recognition that a chief report of impaired function may also be the first implication of activity limitation or participation restriction. A homemaker’s report that “my balance has been getting worse and I’ve fallen several times” may be related to disease involving the vestibular system and to disability created by unsafe ambulation. Similarly, a farmer’s declaration that “I can no longer climb up onto my tractor” not only suggests a neuromuscular or orthopedic disease but also conveys that the disorder has resulted in disability because the patient is not able to fulfill vocational expectations.

History of Present Illness

The history of the present illness is obtained when the patient relates the development of the present illness. When necessary, patients should be asked to define the specific words they use. Specific questions relating to a particular symptom can also help focus the interview. Using these techniques, the physician can gently guide the patient to follow a chronological sequence and to fully describe the symptoms and their consequences. Above all, the patient should be allowed to tell the story. More than one symptom may be elicited during the interview, and the physician should document each problem in an orderly fashion (

Table 1-2) (

1).

A complete list of the patient’s current medications should be obtained. Polypharmacy is commonly encountered in people with chronic disease, at times with striking adverse effects. Side effects of medications can further impede cognition, psychological state, vascular reflexes, balance, bowel and bladder control, muscle tone, and coordination already impaired by the present illness or injury.

The history of the present illness should include a record of handedness, which is important in many areas of rehabilitation.

Functional History

The physiatric evaluation of a patient with chronic disease often reveals impaired function. The functional history enables the physiatrist to characterize the disabilities that have resulted from disease and to identify remaining functional capabilities. Some physicians consider the functional history to be part of the history of the present illness, whereas others view it as a separate segment of the patient interview. The examiner must know not only the functional status associated with the present illness but also the premorbid level of function.

Although the specific organization of the activities of daily living varies somewhat, the following elements of personal independence are constant: communication, eating, grooming, bathing, toileting, dressing, bed activities, transfers, and mobility.

When obtaining the functional history, the physician may record in a descriptive paragraph the patient’s level of independence in each activity. However, functional stability is best communicated, followed over time, and made accessible for study when the physician uses a standard functional assessment scale, as discussed in

Chapter 28.

Communication

Because a major component of physical medicine and rehabilitation practice is patient education, effective communication is essential. The interviewer must assess the patient’s communication options. In the clinical situation, this aspect of the evaluation blurs the distinction between history and physical examination. It is difficult to interact with the patient in a meaningful way without coincidentally examining his or her ability to communicate; significant speech and language deficiencies become obvious. However, for purposes of discussion, certain facets of the assessment relate more specifically to the history and will be discussed here. Additional facets are presented below in the section on the physical examination.

Speech and language pathology has provided clinicians with numerous classification systems for speech and language disorders (see

Chapter 15). From a functional view, the elements of communication hinge on four abilities related to speech and language (

2):

Listening

Reading

Speaking

Writing

By assessing these factors as well as comprehension and memory, the examiner can determine a patient’s communication abilities. Representative questions include the following:

Do you have difficulty hearing?

Do you use a hearing aid?

Do you have difficulty reading?

Do you need glasses to read?

Do others find it hard to understand what you say?

Do you have problems putting your thoughts into words?

Do you have difficulty finding words?

Can you write?

Can you type?

Do you use any communication aids?

Eating

The abilities to present solid food and liquids to the mouth, to chew, and to swallow are basic skills taken for granted by able-bodied people. However, in patients with neurologic, orthopedic, or oncologic disorders, these tasks can be formidable. Dysfunctional eating is associated with far-reaching consequences, such as malnutrition, aspiration pneumonitis, and depression. As in the assessment of other skills for activities of daily living, eating function should be assessed specifically and methodically.

Representative questions include the following:

Can you eat without help?

Do you have difficulty opening containers or pouring liquids?

Can you cut meat?

Do you have difficulty handling a fork, knife, or spoon?

Do you have problems bringing food or beverages to your mouth?

Do you have problems chewing?

Do you have difficulty swallowing solids or liquids?

Do you ever choke?

Do you regurgitate food or liquids through your nose?

Patients with nasogastric or gastrostomy tubes should be asked who helps them prepare and administer their feedings. The type, quantity, and schedule of feedings should be recorded.

Grooming

Grooming may not be considered as important as feeding. However, impaired functioning that leads to deficits in grooming can have deleterious effects on hygiene as well as on body image and self-esteem. Consequently, grooming skills should be of real concern to the rehabilitation team.

Representative questions include the following:

Can you brush your teeth without help?

Can you remove and replace your dentures without help?

Do you have problems fixing or combing your hair?

Can you apply your makeup independently?

Do you have problems shaving?

Can you apply deodorant without assistance?

Bathing

The ability to maintain cleanliness also has far-reaching physical and psychosocial implications. Deficits in cleaning can result in skin maceration and ulceration, skin and systemic infections, and the spread of disease to others. Patients should be questioned about their ability to bath independently.

Representative questions include the following:

Can you take a tub bath or shower without assistance?

Do you feel safe in the tub or shower?

Do you use a bath bench or shower chair?

Can you accomplish a sponge bath without help?

Are there parts of your body that you cannot reach?

For patients with sensory deficits, bathing is also a convenient time for skin inspection, and inquiry about the patient’s inspection habits should be made. For patients using a wheelchair, walker, or other mobility device, architectural barriers to bathroom entry should be determined.

Toileting

To the cognitively intact person, incontinence of stool or urine can be a psychologically devastating deficit of personal independence. Ineffective bowel or bladder control has an adverse impact on self-esteem, body image, and sexuality, and it can lead to participation restriction. The soiling of skin and clothing can result in ulceration, infection, and urologic complications. The physiatrist should vigorously but sensitively pursue questioning about toileting dependency.

Representative questions include the following:

Can you use the toilet without assistance?

Do you need help with clothing before or after using the toilet?

Do you need help with cleaning after a bowel movement?

For patients with indwelling urinary catheters, the usual management of the catheter and leg bag should be examined. If bladder emptying is accomplished by intermittent catheterization, the examiner should determine who performs the catheterization and should have a clear understanding of his or her technique. For patients who have had ostomies for urine or feces, the examiner should determine who cares for the ostomy and should ask the patient to describe the technique.

Feminine hygiene is generally performed while on or near the toilet, so at this point in the interview, it may be appropriate to ask about problems with the use of sanitary napkins or tampons.

Dressing

We dress to go out into the world to be employed in the workplace, to dine in restaurants, to be entertained in public places, and to visit friends. Even at home, convention dictates that we dress to entertain anyone except close friends and family. We dress for protection, warmth, self-esteem, and pleasure. Dependency in dressing can result in a severe limitation to personal independence and should be investigated thoroughly during the rehabilitation interview.

Representative questions include the following:

Do you dress daily?

What articles of clothing do you regularly wear?

Do you require assistance putting on or taking off your underwear, shirt, slacks, skirt, dress, coat, stockings, panty hose, shoes, tie, or coat?

Do you need help with buttons, zippers, hooks, snaps, or shoelaces?

Do you use clothing modifications?

Bed Activities

The most basic stage of functional mobility is independence in bed activities. The importance of this functional level should not be underestimated. Persons who cannot turn from side to side to redistribute pressure and periodically expose their skin to the air are at high risk for development of pressure sores over bony prominences and skin maceration from heat and occlusion. For the person who cannot stand upright to dress, bridging (lifting the hips off the bed in the supine position) will allow the donning of underwear and slacks. Independence is likewise enhanced by an ability to move between a recumbent position and a sitting position. Sitting balance is required to accomplish many other activities of daily living, including transfers.

Representative questions include the following:

When lying down, can you turn onto your front, back, and sides without assistance?

Can you lift your hips off the bed when lying on your back?

Do you need help to sit or lie down?

Do you have difficulty maintaining a seated position?

Can you operate the bed controls on an electric hospital bed?

Transfers

The second stage of functional mobility is independence in transfers. Being able to move between a wheelchair and the bed, toilet, bath bench, shower chair, standard seating, or car seat often serves as a precursor to independence in other areas. Although a male patient can use a urinal to void without having to transfer, a female patient cannot be independent in bladder care without the ability to transfer to the toilet and will probably require an indwelling catheter. Travel by airplane or train is difficult without the ability to transfer from the wheelchair to other seating. Bathing or showering is not independent without the ability to move to the bath bench or shower chair. The inability to transfer to a car seat precludes the use of a motor vehicle with standard seats. Also included in this category is the ability to rise from a seated position to a standing position. Low seats without arm supports present a much greater problem than straight-backed chairs with arm supports.

Representative questions include the following:

Can you move to and from the wheelchair to the bed, toilet, bath bench, shower chair, standard seating, or car seat without assistance?

Can you get out of bed without difficulty?

Do you require assistance to rise to a standing position from either a low or a high seat?

Can you get on and off the toilet without help?

Mobility

Wheelchair Mobility

Although wheelchair independence is more likely than walking to be inhibited by architectural barriers, it provides excellent mobility for the person who is not able to walk. With efficiently engineered, lightweight manual wheelchairs, the energy expenditure required to wheel on flat ground is only slightly greater than that of walking. With the addition of a motorized drive, battery power, and controls for speed and direction, a wheelchair can be propelled even by a person who lacks the upper extremity strength necessary to propel a manual wheelchair, and it can thus help maintain independence in mobility.

Quantification of manual wheelchair skills can be accomplished in several ways. Patients may report in feet, yards, meters, or city blocks the distance that they are able to traverse before resting. Alternatively, the number of minutes they can continuously propel the chair can be specified, or the environment in which they are able to use the chair can be described (e.g., within a single room, around the house, or throughout the community).

Representative questions include the following:

Do you propel your wheelchair yourself?

Do you need help to lock the wheelchair brakes before transfers?

Do you require assistance to cross high-pile carpets, rough ground, or inclines in your wheelchair?

How far or how many minutes can you wheel before you must rest?

Can you move independently about your living room, bedroom, and kitchen?

Do you go out to stores, to restaurants, and to friends’ homes?

With any of these functional levels of wheelchair mobility, patients should be asked what keeps them from going farther afield and whether they need help lifting the wheelchair into and out of an automobile.

Ambulation

The final level of mobility is ambulation. In the narrowest sense of the word, ambulation is walking, and we have used this definition to simplify the following discussion. However, within the sphere of rehabilitation, ambulation may be any useful means of movement from one place to another. In the view of many rehabilitation professionals, the person with a bilateral above-knee amputation ambulates with a manual wheelchair, the patient with C4 tetraplegia ambulates with a motorized wheelchair, and the survivor of polio in an underdeveloped country might ambulate by crawling. Driving a motor vehicle may also be considered a form of ambulation. Ambulation ability can be quantified the same way wheelchair mobility is quantified. Persons may report the distance they are able to walk, how long they can walk before they require a rest period, and the scope of the environment within which they walk.

Representative questions include the following:

Do you walk unaided?

Do you use a cane, crutches, or a walker to walk?

How far or how many minutes can you walk before you must rest?

What stops you from going farther?

Do you feel unsteady or do you fall?

Can you go upstairs and downstairs unassisted?

Do you go out to stores, to restaurants, and to friends’ homes?

Can you use public transportation (e.g., the bus or subway) without assistance?

Operation of a Motor Vehicle

In the perception of many patients, full independence in mobility is not attained without the ability to operate a motor vehicle on one’s own. Although driving skills are by no means necessary for urban dwellers with readily available public transportation, they may be essential to persons living in a suburban or rural environment. Driving skills should always be assessed in patients of driving age.

Representative questions include the following:

Do you have a valid driver’s license?

Do you own a car?

Do you drive your car to stores, to restaurants, and to friends’ homes?

Do you drive in heavy traffic or over long distances?

Do you drive in low light or after sunset?

Do you use hand controls or other automobile modifications?

Have you been involved in any motor vehicle accidents or received any citations for improper operation of a motor vehicle since your illness or injury?

Past Medical History

The past medical history is a record of any major illness, trauma, or health maintenance since the patient’s birth. The effects of certain past conditions will continue to affect the present level of function. Identifying these conditions affords an opportunity to better characterize the patient’s baseline level of function before the present disorder. The examiner must take special care to decipher whether the patient’s diagnostic terms accurately represent the true diagnoses. Although many past conditions associated with extensive immobilization, deconditioning, and disability are themselves amenable to rehabilitation measures, such conditions tend to affect the goals for future rehabilitation efforts.

Case 5

PB, a 66-year-old woman, was referred for rehabilitation after an above-knee amputation of her right leg because of vascular disease. Her past history was notable for a right cerebral infarction 7 years earlier. Despite comprehensive rehabilitation after the stroke, PB was able to walk only one block with a quadruped cane and an ankle-foot orthosis because of spastic left hemiparesis.

Comment: After prosthetic fitting and training, most people in this age group with an above-knee amputation regain ambulation skills, albeit with a cane or other gait aid. However, because PB had a preexisting ambulation disability due to the left hemiparesis that had occurred before amputation, her rehabilitation goals included a wheelchair prescription, with consideration of a hemichair if she could not wheel with her left arm, and training in wheelchair activities. Although ambulation beyond a few yards was not feasible, a preparatory prosthesis with a manual knee lock was provided on a trial basis to determine whether it aided in transfers. For PB, ambulation disability was dictated more by her previous impairments than by impairments associated with her present illness.

All elements of the standard past medical history should be completed; however, a history of neurologic, cardiopulmonary, or musculoskeletal disease should alert the physiatrist to special needs of the patient. Psychiatric disorders are also of

special interest to the physiatrist and are discussed below in the section on the psychological and psychiatric history.

Neurologic Disorders

Most frequently encountered in older populations but possibly present in any age group, a past history of neurologic disease can have a tremendous impact on the rehabilitation outcome of an unrelated current illness. Whether congenital or acquired, preexisting cognitive impairment places restrictions on educationally oriented rehabilitation intervention. Disorders with sensory manifestations such as loss of touch, pain, or joint position or afflictions that are characterized by perceptual dysfunction can retard the patient’s ability to monitor performance during the acquisition of new functional skills. These maladies also render patients more likely to be unresponsive to soft-tissue injury from prolonged or excessive skin surface pressures during long periods of immobility. When these conditions are coupled with preexisting visual or auditory impairment, the function is further encumbered. Likewise, new motor learning can be inhibited by a residual motor deficit that results in spasticity, weakness, or decreased endurance. A diligent search for antecedent neurologic disease should be a fundamental part of the rehabilitation evaluation.

Cardiopulmonary Disorders

For patients with motor disabilities, the activities of daily living require more than the normal expenditure of energy. When preexisting cardiopulmonary disorders limit the patient’s capacity to tolerate the greater energy expenditures imposed by motor impairment, they can result in additional functional deficits. This is also the case with many forms of hematologic, renal, and hepatic dysfunction. The physician should gather as much cardiopulmonary data as needed to estimate cardiac reserve accurately. Only when disease of the cardiopulmonary system is identified and addressed can medical intervention be initiated and rehabilitation tailored to maximize cardiac reserve.

Musculoskeletal Disorders

Weakness, joint ankylosis, or instability from previous trauma or arthritis, amputation, and other musculoskeletal dysfunctions can all affect functional capacity deleteriously. A search for such disorders is a necessary prerequisite to a complete physiatric evaluation.

Review of Systems

The systems should be thoroughly reviewed to screen for clues to disease not otherwise identified in the history of the present illness or in the past medical history. Many diseases have the potential to cause adverse effects on rehabilitation outcomes. However, as described previously, certain disorders are of special interest to the physiatrist. This part of the evaluation considers constitutional, head and neck, respiratory, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, musculoskeletal, neurologic, psychiatric, endocrine, and dermatologic symptoms.

Constitutional Symptoms

Of particular interest to the examiner are suggestions of infection and nutritional deficiency. Fatigue can be a prominent symptom in patients with neurologic and neuromuscular conditions such as stroke, multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or poliomyelitis sequelae, or with other conditions such as obstructive sleep apnea or chronic pain syndromes.

Head and Neck Symptoms

Vision, hearing, and swallowing deficits must be identified.

Respiratory Symptoms

Any pulmonary condition that inhibits delivery of oxygen to the tissues will adversely affect endurance. Symptoms such as dyspnea, cough, sputum, hemoptysis, wheezing, and pleuritic chest pain should be identified.

Cardiovascular Symptoms

The manifestations of heart disease restrict cardiac reserve and endurance. When identified, many cardiovascular conditions can be ameliorated through medical management. Identifying arrhythmias may help prevent recurrent strokes of embolic cause. The presence of chest pain, dyspnea, orthopnea, palpitations, or light-headedness should be determined.

Peripheral vascular disease is the leading cause of amputation. The potential for ulceration and gangrene caused by bed rest, orthoses, pressure garments, and other rehabilitation equipment can be minimized if peripheral disease is recognized. The patient should be asked about claudication, foot ulcers, and varicosities.

Gastrointestinal Symptoms

Almost any form of gastrointestinal tract disease can result in nutritional deficiency, a particularly insidious condition that limits rehabilitation efforts more frequently than previously realized (

3). Bowel control is of special interest for patients with neurologic disorders. These patients should be asked about incontinence, bowel care techniques, and use of laxatives.

Genitourinary Symptoms

Manifestations of neurogenic bladder must be sought. Questions should be asked about specific fluid intake, voiding schedules, specific bladder-emptying techniques, urgency, frequency, incontinence, retention and incomplete emptying, sensation of fullness and voiding, dysuria, pyuria, infections, flank pain, hematuria, and renal stones.

For female patients, a menstrual and pregnancy history should be obtained, and inquiries should focus on dyspareunia, vaginal and clitoral sensation, and orgasm. Male patients should be asked about erection, ejaculation, progeny, and pain during intercourse.

Musculoskeletal Symptoms

The musculoskeletal system review must be thorough because of the likelihood of musculoskeletal dysfunction in patients in a rehabilitation program. The examiner should ask about

muscle pain, weakness, fasciculation, atrophy, hypertrophy, skeletal deformities and fractures, limited joint motion, joint stiffness, joint pain, and swelling of soft tissues and joints.

Neurologic Symptoms

Because of the increased prevalence of neurologic disorders in patients in a rehabilitation program, a methodical neurologic review should always be performed. The following areas should be addressed: sense of smell, diplopia, blurred vision, visual field cuts, imbalance, vertigo, tinnitus, weakness, tremors, involuntary movements, convulsions, depressed consciousness, ataxia, loss of touch, pain, temperature, dysesthesia, hyperpathia, and changes in memory and thinking.

Chewing, swallowing, hearing, reading, and speaking may be addressed in either the functional history or the review of systems.

Psychiatric Symptoms

Psychological and psychiatric issues can be discussed during the review of symptoms. However, we prefer to explore this area while obtaining the psychosocial history for the patient profile.

Endocrine Symptoms

Screening questions should be presented to address intolerance to hot or cold, excessive sweating, increase in urine, increase in thirst, and changes in skin, hair distribution, and voice.

Dermatologic Symptoms

Rash, itching, pigmentation, moisture or dryness, texture, changes in hair growth, and nail changes should be questioned.

Patient Profile

The patient profile provides the interviewer with information about the patient’s present and past psychological state, social milieu, and vocational background.

Personal History

Psychological and Psychiatric History

Any present illness accompanied by functional loss can be psychologically challenging. A quiescent major psychiatric disturbance may resurface during such stressful times and may hinder or halt rehabilitation efforts. When the examiner is able to identify a history of psychiatric dysfunction, the necessary support systems to lessen the likelihood of recrudescence can be applied prophylactically during rehabilitation. The examiner should seek a history of previous psychiatric hospitalization, psychotropic pharmacologic intervention, or psychotherapy. The patient should be screened for past or current anxiety, depression and other mood changes, sleep disturbances, delusions, hallucinations, obsessive and phobic ideas, and past major and minor psychiatric illnesses. A review of the patient’s prior and current responses to stress often helps the rehabilitation team to better understand and modify behavioral responses to catastrophic illness or trauma. Therefore, it is important to know the patient’s emotional responses to previous illness and family troubles and to know how the stress of the current illness is being addressed. If initial screening suggests any abnormality, a clinical psychologist can conduct tests to clarify psychological symptoms or to identify a personality disturbance.

Lifestyle

Leisure activities can promote both physical health and emotional health. The patient’s leisure habits should be reviewed to identify special rehabilitation measures that might return independence in these activities. Examples of questions to consider include the following (

4):

What sorts of interests do you have?

Do you enjoy physical endeavors, sports, the outdoors, and mechanical avocations (i.e., motor oriented) more than sedentary activities?

Are you more interested in intellectual pursuits (i.e., symbol oriented) than physical endeavors?

Do you derive the most pleasure from social interactions, organizations, and group functions (i.e., interpersonally oriented)?

Have you been actively pursuing any of these interests?

The work-oriented person without avocational interests before the present illness will need recreational counseling during rehabilitation.

Diet

Inadequate nutrition may inhibit rehabilitation efforts. In addition, even after initial myocardial and cerebrovascular events due to atherosclerosis, some secondary prevention can be accomplished through dietary intervention. The examiner should determine the patient’s ability to prepare meals and snacks, as well as the patient’s usual dietary habits and special diets.

Alcohol and Drugs

Drug, alcohol, and nicotine use must be assessed. Patients with cognitive, perceptual, and motor deficits can be further impaired to a dangerous degree through substance abuse. The use of alcohol or drugs is frequently a factor in head and spinal cord injuries. Identifying abuse and dependency provides an opportunity to help the patient modify future behavior through counseling. The CAGE questionnaire is a brief but useful screening vehicle for assessing alcohol abuse and dependency (

Table 1-3); a single affirmative answer should initiate further investigation (

5).

Social History

Family

Catastrophic illness in a family member places enormous stress on the rest of the family. When the family is already facing other problems with interaction, health, or substance abuse, the potential is greater for disintegration of the family unit. This tendency is unfortunate because the availability of a sturdy support system of family and friends can be as predictive of disposition as it is of functional outcome. The examiner should determine the patient’s marriage history and marital status and should obtain the names and ages of other family members who live in the home. The established roles of each member should be understood clearly (e.g., who handles the finances, the cooking, the cleaning, or the discipline). The examiner should also determine whether other family members live nearby. To ascertain the availability of all potential assistants, the examiner should inquire about their willingness and ability to participate in the care of the patient and about their work or school schedule.

Home

The patient’s home design should be reviewed to identify architectural barriers. The examiner should determine whether the patient owns or rents the home, the location of the home (e.g., urban, suburban, or rural), the distance between the home and rehabilitation services, the number of steps into the home, the presence of (or room for) entry ramps, and the accessibility of the kitchen, bath, bedroom, and living room.

Vocational History

Education and Training

Although education does not predict intellectual function, the educational level achieved by the patient may suggest intellectual skills upon which the rehabilitation team can draw during the patient’s convalescence. In addition, when coupled with the assessment of physical function, the educational background will dictate future educational and training needs. After determining the years of education completed by the patient and whether high school, undergraduate, or graduate degrees were obtained, the examiner should review the patient’s performance. The acquisition of special skills, licenses, and certifications should be noted. Future vocational goals are always important to address but are of particular concern with adolescent patients. A discussion of these goals should indicate the need for and the type of interest, aptitude, and skills testing and any appropriate vocational counseling.

Work History

An understanding of the patient’s work experience can help determine the need for further education and training. It also provides an idea of the patient’s motivation, reliability, and self-discipline. The duration and type of previous jobs and the reason for job changes should be recorded. Not only titles but also actual job descriptions must be obtained, and the patient should be asked about architectural barriers within the workplace. These principles also apply to the patient who works at home. In addition, the examiner should define the specific expectations related to meal preparation, shopping, home maintenance, cleaning, child rearing, and discipline. Finally, the examiner should ask where clothes are washed and whether architectural barriers prevent the patient from reaching appliances or areas in the home and yard.

Finances

The physical medicine and rehabilitation team, in particular the social worker or case manager, should have a basic understanding of the patient’s income, investment, and insurance resources, disability classifications, and debts. This financial information is important in determining the services and assistance to which an individual patient may be entitled.

Family History

The family history can be used to identify hereditary disease in the family and to assess the health of people in the patient’s home support system. Knowledge of the health and fitness of the spouse and other family members can aid dismissal planning.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The physical examination performed by the physiatrist has much in common with the general medical examination. Of necessity, it is a well-practiced art. Through perceptions gleaned from observation, palpation, percussion, and auscultation, the examining physician seeks physical findings to support and formulate the diagnosis and to screen for other conditions not suggested by the patient history.

The physical examination also differs from the general medical examination. After investigating the physical findings that help to establish the medical diagnosis, the physiatrist still has two principal tasks:

To scrutinize the patient for physical findings that can help define the functional impairments emanating from the disease

To identify the patient’s remaining physical, psychological, and intellectual strengths that can serve as the base for reestablishing functioning

Physical medicine and rehabilitation emphasizes the orthopedic and neurologic examinations and makes assessment of function an integral part of the overall physical examination.

Severe motor, cognitive, and communication impairments make it difficult or impossible for some patients to follow the directions of the physician, and these impairments limit certain traditional physical examination maneuvers. Thus, creativity is often required to accomplish the examination. Expert examination skills are particularly necessary in such situations.

We assume that the reader is competent in the performance of the general medical examination (

6). The following discussion places priority on the aspects of the physical examination that have special relevance to physical medicine

and rehabilitation. The major segments of the physical examination are vital signs and general appearance, integument and lymphatics, head, eyes, ears, nose, mouth and throat, neck, chest, heart and peripheral vascular system, abdomen, genitourinary system and rectum, musculoskeletal system, neurologic examination, and functional examination.

Vital Signs and General Appearance

The recording of blood pressure, pulse, temperature, weight, and general observations is important. The identification of hypertension may be meaningful to the secondary prevention of stroke and myocardial infarction. Supine, sitting, and standing blood pressures should be obtained to rule out orthostasis in any patient who has had unexplained falls, light-headedness, or dizziness. Tachycardia can be the initial manifestation of sepsis in a patient with high-level tetraplegia, or it can suggest pulmonary embolism in an immobilized patient. Initial weight recordings are invaluable to identify and follow up malnutrition, obesity, and fluid and electrolyte disorders common after various forms of brain injury. A notation should be made if patients act hostile, tense, or agitated or if their behavior is uncooperative, inappropriate, or preoccupied.

Integument and Lymphatics

Skin disorders are frequently encountered in patients undergoing physical rehabilitation. Prolonged pressure in patients with peripheral vascular disease, sensory disorders, immobility, and altered consciousness often results in damage to skin and underlying tissues. Many diseases common to disabled persons, and their treatments, render the skin more prone to trauma and infection. Skin problems that are only somewhat bothersome to able-bodied people can be devastating to persons with disabilities when they interfere with the use of prostheses, orthoses, and other devices.

The patient’s skin should be inspected in appropriate lighting. By considering the skin as each separate body region is examined, the physiatrist can study the entire body surface without total exposure of the patient. In particular, the skin over bony prominences and in contact with prosthetic and orthotic devices should be examined for lichenification, erythema, or breakdown. Intertriginous areas should be inspected for maceration and ulceration; the distal lower extremities in patients with vascular disease should be examined for pigmentation, hair loss, and breakdown; and the hands and feet in insensate patients should be observed for unrecognized trauma. All common lymph node sites should be palpated for enlargement and tenderness, and areas of edema should be palpated for pitting.

Head

The head should be inspected for signs of past or present trauma. Gentle palpation should be performed for evidence of previous trauma or neurosurgical procedures, shunt pumps, and other craniofacial abnormalities. Auscultation for bruits should be done when considering vascular malformations.

Eyes

Unrecognized acuity errors can hamper rehabilitation efforts, especially in patients needing adequate eyesight to compensate for disorders of other sensory systems. With the patient’s usual eyewear in place, far and near vision should be tested with the use of standard charts. If charts are not available, the patient’s vision can be compared with the examiner’s vision by object identification and description for far vision and by reading materials of several print sizes for near vision. Findings can be substantiated with refraction when circumstances permit. An ophthalmoscopic examination should be performed; if dilatory agents are necessary, one with a short duration can be used; notation should be made in the patient’s chart of the time of administration and the name of the preparation. Evidence of erythema and inflammation of the globe or conjunctiva should be sought; aphasic patients and those with altered consciousness may not adequately express the pain of acute glaucoma or the discomfort of conjunctivitis. The eyes of comatose patients should be inspected for inadequate lid closure; deficient lubrication should be compensated for to prevent corneal ulcerations.

Ears

Unrecognized hearing impairment can limit rehabilitation efforts. Hearing acuity can be checked with the “watch test” or by having the patient listen to and repeat words that are whispered. If a unilateral hearing deficit is identified, the Weber test and the Rinne test can be used to determine whether it is a nerve or conductive loss. Findings can be substantiated with an audiogram. An otoscopic examination should be performed. If otorrhea is present in a head-injured patient, Benedict solution can be used to assess the presence of sugar, which indicates cerebrospinal fluid.

Nose

A routine examination of the nose, including olfactory function, is generally sufficient. Clear or blood-tinged drainage in a head-injured patient indicates the presence of cerebrospinal fluid.

Mouth and Throat

The oral and pharyngeal mucosa should be inspected for poor hygiene and infections (e.g., candidiasis in patients taking corticosteroids or broad-spectrum antibiotics), the teeth for disrepair, and the gums for gingivitis or hypertrophy. Dentures should be checked for fit and maintenance. In patients with arthritis or trauma, the temporomandibular joints should be inspected and palpated for crepitation, tenderness, swelling, or limited motion. Any of these problems can impair food and fluid intake, resulting in poor nutrition.

Neck

A routine examination of the neck is generally sufficient. The examiner should listen for carotid bruits in patients with atherosclerosis and cerebrovascular disorders. In patients with musculoskeletal disorders, range of motion (ROM) should be assessed. However, neck motion need not be checked in

patients with recent trauma or chronic polyarthritides until radiographic studies have ruled out fracture or instability.

Chest

Tolerance to exercise is considerably affected by pulmonary function. For patients whose exercise tolerance is already compromised by neurologic or musculoskeletal disease, the examiner must search rigorously for pulmonary dysfunction to minimize the deficit. The standard medical maneuvers are usually sufficient; however, certain aspects of the chest examination merit mention.

The chest wall should be inspected to note the rate, amplitude, and rhythm of breathing. The presence of cough, hiccups, labored breathing, accessory muscle activity, and chest wall deformities should be noted. Respiration may be restricted by rheumatologic disorders such as advanced spondyloarthropathies and scleroderma. Likewise, restrictive pulmonary disease with hypoventilation is common in muscular dystrophy and other neuromuscular diseases, severe kyphoscoliosis, and chronic spinal cord injuries. Tachypnea and tachycardia may be the only readily apparent manifestations of pulmonary embolism, pneumonia, or sepsis after a high-level spinal cord injury. The finding of a barrel chest may lead the examiner to identify obstructive pulmonary disease so that medical management can minimize its effect on functioning.

The patient should be instructed to cough, and the force and efficiency of this action should be noted. If the cough is weak, the patient can be assisted by exerting manual pressure over the abdomen coincidentally with the cough to observe the effect. The chest wall should be palpated for tenderness, deformity, and transmitted sounds. During the acute care of a head-injured patient, rib fractures may be missed. Percussion should be performed to document diaphragmatic level and excursion. Auscultation should be performed to characterize breath sounds and to identify wheezes, rubs, rhonchi, and rales. Pneumonitis can be especially insidious in the immunosuppressed patient.

When pulmonary disease is suspected, further investigation with pulmonary function tests and a determination of blood gas levels may need to be undertaken. If the patient has a tracheostomy, the skin around the opening should be examined, the type of apparatus recorded, and cuff leaks noted. Screening for breast malignancy may be necessary in women and men alike.

Heart and Peripheral Vascular System

As with pulmonary disease, cardiovascular dysfunction can adversely affect exercise tolerance already encumbered by neurologic or musculoskeletal disease. When cardiovascular disorders are identified, intervention can relieve or reduce deleterious effects on exercise tolerance and general health. Implementation of appropriate secondary prevention measures for embolic stroke is contingent upon the identification of arrhythmias, valvular disease, and congenital anomalies.

In the clinical situation, peripheral circulation is usually assessed during examination of the patient’s limbs. When bracing is being considered, the examiner should search for the pallor and cool dystrophic skin of arterial occlusive disease; inappropriate devices may lead to edema and subsequent skin breakdown. Deep venous thrombosis is a major risk to immobilized patients, who should be examined for varicose and incompetent veins. Bedside Doppler studies should be used as necessary to help delineate arterial or venous concerns such as Raynaud phenomenon.

Abdomen

In many patients, the general medical examination of the abdomen is the only necessary screen to identify abnormality and to assess gastrointestinal tract symptoms. In patients with widespread spasticity (e.g., due to multiple sclerosis or myelopathy), inspection and auscultation should precede palpation and percussion. Manipulation of the abdominal wall often results in a wave of increased tone that will temporarily impede the rest of the abdominal examination. Vigorous abdominal palpation in patients with disordered peristalsis from certain central nervous system diseases may initiate regurgitation of stomach contents. Such patients should be examined gently when they are in a partially reclined position.

Genitourinary System and Rectum

During any comprehensive evaluation, the genitalia should be examined. A thorough evaluation of the male and female genitalia is particularly necessary for patients with disorders of continence, micturition, and sexual function. Incontinence in patients of either sex and in male patients using an external collecting device such as the condom catheter can result in maceration and ulceration. Thus, the penile skin in male patients, the periurethral mucosa in female patients, and all intertriginous perineal areas should be examined. The scrotal contents should be palpated for orchitis and epididymitis in male patients with indwelling catheters. Incontinence from neurogenic causes is common in patients undergoing rehabilitation; however, the examiner should check for a cystocele or other structural cause of incontinence that can be remediated. Patients with long-term use of indwelling catheters should be checked for external urethral meatal ulceration, and male patients should be checked for penile fistulas. If urinary retention is suspected, the physical examination should be followed by an in-and-out catheterization to measure residual urine.

The rehabilitation assessment is not complete without digital examination of the rectum and anus to check anal tone and perineal sensation. In any patient with suspected central nervous system, autonomic, or pelvic disease, the bulbocavernosus reflex should be evaluated to monitor sphincter tone by firmly compressing the glans of the penis or clitoris with one hand while inserting the index finger of the other hand into the anus. Sphincter tone is increased with many upper motor neuron lesions, whereas it is decreased or absent with lesions peripheral to the sacral cord (S2-4).

Musculoskeletal System

Disorders of the musculoskeletal system are a major portion of the pathologic conditions addressed by the rehabilitation

physician. The examiner must possess expert skills in the evaluation of all musculoskeletal components and should systematically assess the bone, joint, cartilage, ligament, tendon, and muscle in each body region. Accomplishing this task requires full familiarity with surface landmarks and underlying anatomical features.

The assignment of many examination components to the neurologic or musculoskeletal examination is arbitrary because the neuromusculoskeletal function is so integrated. Examination of the musculoskeletal system is divided into inspection, palpation, ROM assessment, joint stability assessment, and muscle strength testing.

Inspection

Musculoskeletal inspection should be performed for scoliosis, abnormal kyphosis, and lordosis; joint deformity, amputation, absence and asymmetry of body parts (leg-length discrepancy); soft-tissue swelling, mass, scar, and defect; and muscle fasciculations, atrophy, hypertrophy, and rupture. At times, the dysfunction may be subtle and decipherable only through careful observation. While proceeding with the examination, the physician should note any wary and tentative movements of the patient indicative of pain, any exaggerated and inconsistent conduct indicative of malingering, and any bizarre behavior indicative of conversion reaction.

Palpation

Localized abnormalities (e.g., areas of tenderness or deformity) identified through inspection and any body regions of concern to the patient should be palpated to ascertain their structural origins. For an abnormality, it is important to first determine whether its basic consistency is that of soft tissue or bone and whether it is of normal anatomical structure. An attempt should be made to further identify soft-tissue abnormalities as pitting or nonpitting edema, synovitis, or mass lesions.

All skeletal elements near areas of hemorrhage and ecchymosis in patients with altered consciousness should be palpated. The elderly patient with traumatic subdural hematoma may have an extremity fracture associated with a fall. During the critical care of a motorcyclist with a head injury, an incidental fracture may have been missed. Likewise, any in-hospital fall by a confused patient warrants a search for occult bony trauma.

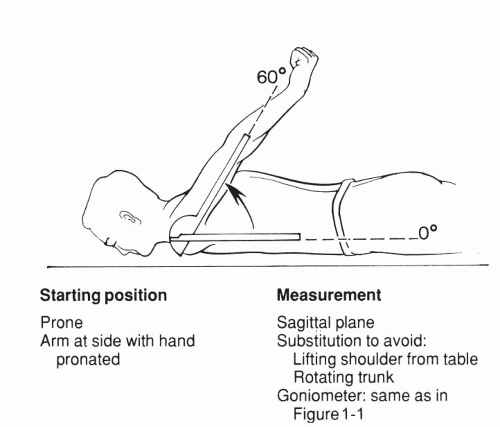

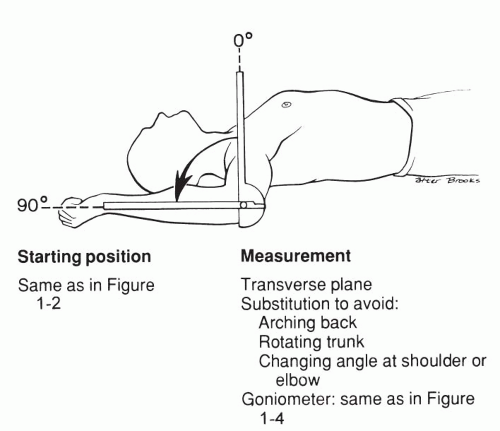

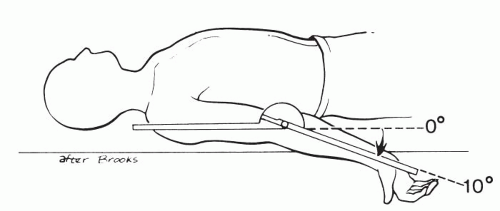

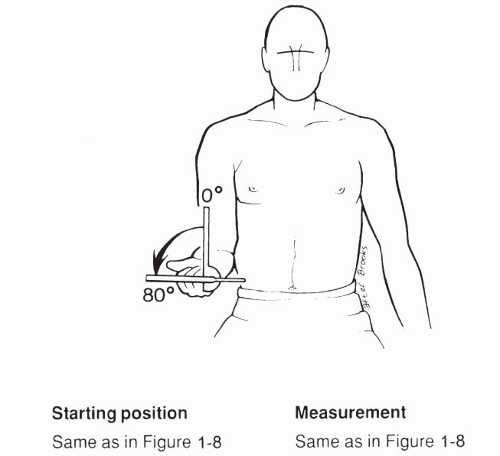

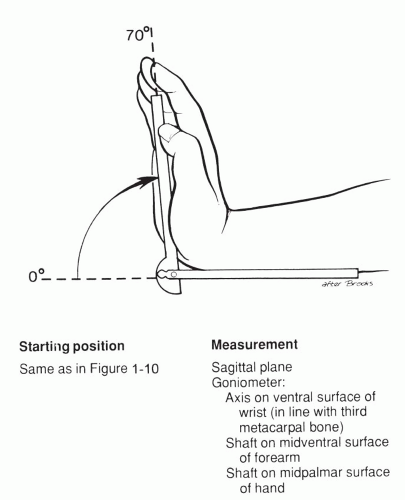

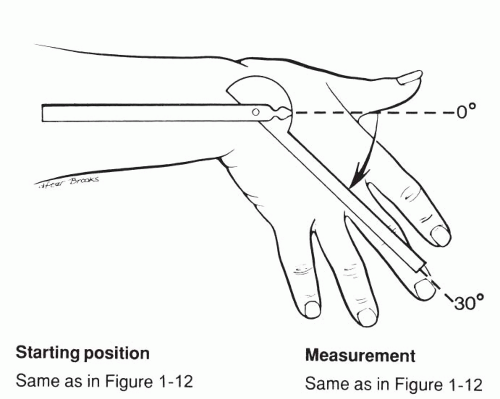

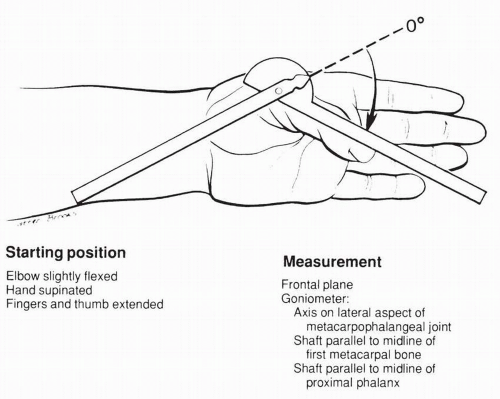

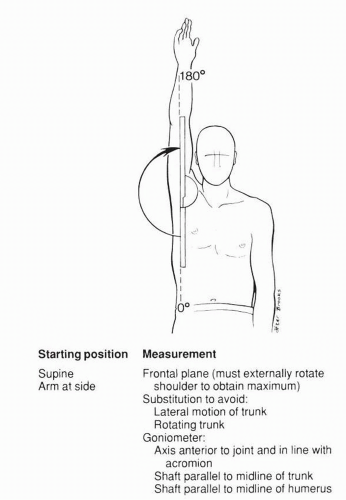

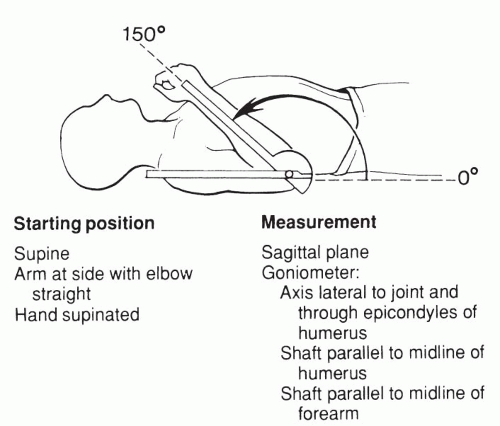

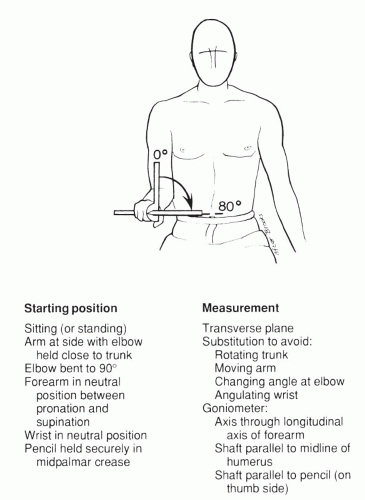

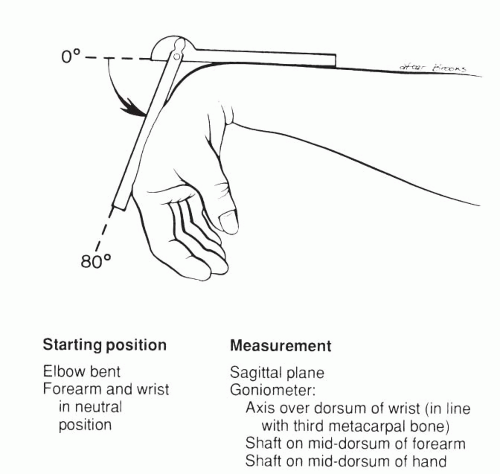

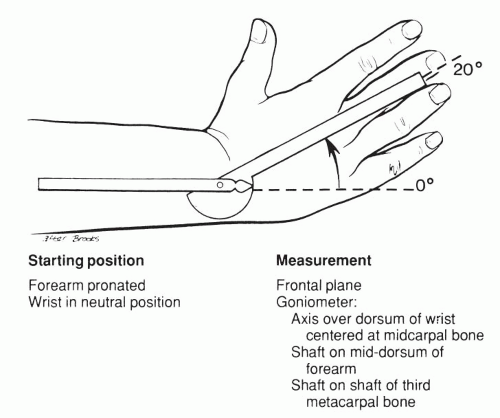

ROM Assessment

Human joint motion is measured during clinical evaluation by many health care professionals for various reasons, including initial evaluation, evaluation of treatment procedure, feedback to the patient, assessment of work capacity, or research studies. When identifying a starting point for measuring the ROM of a joint, we prefer to regard the anatomical position as the baseline (zero starting point). If rotation is being measured, the midway point between the normal rotation range should be the zero starting point (

7).

Considerable variation exists among the ROM measurements of different persons. Factors such as age, sex, conditioning, obesity, and genetics can influence the normal ROM. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons has reported the average ROM measurements for joints in the human body (

8).

When the patient does not assist the examiner during an assessment, the measurement is a passive ROM. If the patient performs the ROM maneuver without assistance, then the range is an active ROM. If comparisons are made between active and passive ROMs, the starting position, stabilization, goniometer, alignment, and type of goniometer should be the same.

Different methods are available for recording the results of ROM measurements. Graphic recordings are often helpful for providing feedback to the patient or a third party. Sometimes the difference between the patient’s ROM and a normal ROM is of special interest to the examiner, such as when the surgeon wants to evaluate finger motion periodically as a guide to recovery after a hand operation.

The goniometer position, starting position, and average ROM of the more commonly measured joints are shown in

Figures 1-1,

1-2,

1-3,

1-4,

1-5,

1-6,

1-7,

1-8,

1-9,

1-10,

1-11,

1-12,

1-13,

1-14,

1-15,

1-16,

1-17,

1-18,

1-19,

1-20,

1-21,

1-22,

1-23,

1-24,

1-25 and

1-26.