Chapter 35 Clinical and Epidemiologic Features of Lupus Nephritis

Introduction

Renal involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) remains the strongest predictor of overall patient morbidity and mortality.1 Clinical features of lupus glomerulonephritis have been recognized since the 1920s with the first pathologic findings described by 1935. Before the development of corticosteroid therapy and nitrogen mustard in the late 1940s and hemodialysis in the 1960s, the onset of lupus nephritis was associated with a significant risk of death within 2 years.2

Survival in lupus has improved with greater than 90% 10-year survival in many cohorts; the survival in patients with lupus nephritis lags behind at 83% over 10 years. Although mortality rates from SLE have been relatively stable among Caucasians, deaths have increased among African-American patients, particularly women ages 45 to 64 years, since the 1970s.3 Renal involvement remains more frequent and severe among patients with African ancestry, children, and male patients.4,5 In a London cohort of 156 patients with lupus nephritis followed for 30 years (1975 to 2005), the 5-year mortality rate (60%) significantly decreased among patients identified in the first and second decades, but the rate has not changed in the last 10 years.6 The 5-year survival rate for end-stage renal disease (ESRD) remained constant through the study. Similarly, a long-term study of 100 patients of Dutch descent diagnosed with lupus nephritis between 1971 and 1995 found no decrease in the risk of ESRD over the study. The authors observed excess mortality with standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) of 9.0, 6.2, and 6.6 among patients diagnosed in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, compared with national age-, sex-, and calendar year–matched death rates.7 In the United States, the incidence of ESRD from lupus nephritis from 1996 to 2004 did not decline, despite the evolution of treatment and management of important co-morbidities.8

Clinical Definition of Lupus Nephritis

Active lupus nephritis can be defined clinically and histopathologically. Clinical evaluation for lupus nephritis includes dipstick and microscopic urinalysis, urinary protein and creatinine excretion, serum creatinine determinations, and serologic studies—anti–double stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) antibody titers and serum complement components C3 and C4. The disease may further be defined as nephrotic by low serum albumin and elevated cholesterol levels. The urinary sediment is useful to characterize disease activity. The presence of glomerular hematuria, leukocyturia, or casts is typical only during periods of disease activity. The most common abnormal sediment findings are leukocyturia, hematuria, and granular casts. Chronic changes observed with nephrotic syndrome include waxy casts, oval fat bodies, and lipid droplets. In one series of 128 patients with SLE nephritis, red cell casts were present in only 39 (7.5%) of the patients.9 Active lupus nephritis is often preceded by rising anti-DNA antibody titers and hypocomplementemia, especially low complement C3.

Classification Criteria

Lupus renal disease may also be defined immunohistopathologically. Tissue obtained by renal biopsy should be evaluated by light microscopy (LM), immunofluorescence (IF), and electron microscopy (EM). A correlation exists between the pathologic class of lupus nephritis and its clinical features.10,11 Despite this association, patients with so-called silent lupus nephritis have normal urinalyses, an absence of proteinuria, and normal serum creatinine; however, on renal biopsy, they also have anywhere from mesangial to proliferative nephritis.12 Fortunately, progressive loss of renal function typically does not occur without changes in urinary sediment and protein excretion. Lupus glomerulonephritis is now defined by the International Society of Nephrology (ISN); its classification was developed by nephropathologists in conjunction with rheumatologists and nephrologists.13 Because prognosis and therapeutic guidelines from many clinical trials have been based on the prior system, the ISN classification (discussed in Chapter 49) must be compared with the preexisting World Health Organization (WHO) classification system and the activity and chronicity indices developed by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The activity and chronicity indices are no longer scored numerically in the ISN classification, but the features are described. Patients with prior biopsies may have WHO staging to compare with ISN classification on subsequent biopsies. Studies have validated the relationship of the ISN scoring system with clinical outcomes to date and have shown improved inter-rater reliability.14

Histopathologic Classifications of Lupus Nephritis

Lupus nephritis is extremely pleomorphic. All four renal compartments—glomeruli, tubules, interstitium, and blood vessels—may be affected. Adjacent glomeruli from a single biopsy may show variable involvement, as may the biopsies from patients with similar clinical manifestations. Over time, glomerular lesions may transform from one pattern to another. Throughout the years, investigators have sought to define and quantify the many morphologic lesions of lupus nephritis in a comprehensive, systematic fashion. The earliest classifications of renal involvement in patients with SLE divided glomerular changes only into mild forms (lupus glomerulitis), severe proliferative forms (active lupus glomerulonephritis), and membranous glomerulopathy.15,16

Three major classification systems have been proposed over the last three decades. The original WHO classification was formulated in 1974 and recognized five major classes of lupus nephritis.17,18 In 1982, a modified WHO classification was promulgated by the International Study of Kidney Disease in Children (ISKDC) with further revisions in 1995.19,20 It defines six major classes of lupus nephritis and a large number of subclasses with an emphasis on distribution, activity, and chronicity of the lesions. Although significantly more detailed and precise than the original classification, the modified WHO classification has not been as widely accepted because of its greater complexity with excessive reliance on subclasses. Moreover, its treatment of mixed or overlapping classes of lupus nephritis has been controversial. A third classification, proposed in 2004 by a consensus conference organized jointly by the ISN and the Renal Pathology Society (RPS), retains the simplicity of the original WHO classification but incorporates some of the refinements introduced by the modified WHO classification.13,21 The ISN/RPS classification has the advantage of standardizing pathologic criteria and defining the distinctions among the classes more precisely.

Pathologic Features of Lupus Nephritis According to the International Society of Nephrology/Renal Pathology Society Classification

Class I: Minimal Mesangial Lupus Nephritis

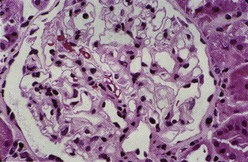

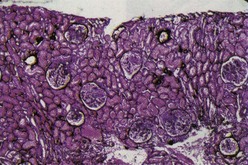

Class I denotes normal glomeruli by LM with mesangial immune deposits detected by IF or EM or both. The original WHO class I, defined as an entirely normal renal biopsy, was rarely if ever encountered because such patients typically have no clinical renal abnormalities and are not subjected to renal biopsy. Therefore the “normal” category was eliminated from the ISN/RPS classification. By LM the glomeruli are normocellular (Figure 35-1). By IF, immune deposits are limited to the mesangium. The mesangial deposits tend to be small and vary from segmental to global in distribution. By EM, corresponding electron-dense deposits are present in the mesangium but without involvement of the peripheral glomerular capillary walls.

Class II: Mesangial Proliferative Lupus Nephritis

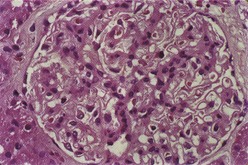

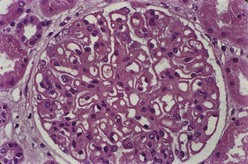

Class II is defined as pure mesangial hypercellularity of any degree and/or mesangial matrix expansion by LM with mesangial immune deposits. Mesangial hypercellularity is defined as three or more mesangial cells in mesangial areas away from the vascular pole, assessed in 3-micron-thick histologic sections. The mesangial proliferation is usually mild to moderate and does not compromise the glomerular capillary lumina (Figure 35-2). By IF, granular mesangial immune deposits are visualized. The pattern by IF outlines the axial framework of the glomerulus, corresponding to the mesangial stalk. By EM, electron-dense deposits are revealed within the mesangial matrix. Strictly speaking, pure class II lupus nephritis should have no detectable subendothelial or subepithelial deposits. However, in practice, some cases of purely mesangial proliferative lupus nephritis will manifest rare, small subendothelial electron-dense deposits, particularly extending out from the adjacent mesangium. Lupus nephritis with severe but purely mesangial hypercellularity and without obliteration of the capillary lumina may pose difficulties in classification. If EM and IF confirm that the immune deposits are limited to the mesangium, then even cases of severe diffuse mesangial proliferation should be classified as class II. If significant subendothelial deposits are observed by IF or EM or if they are visible by LM, then the case should be classified as focal proliferative (class III) or diffuse proliferative (class IV), depending on their distribution.

Class III: Focal Lupus Nephritis and Class IV: Diffuse Lupus Nephritis

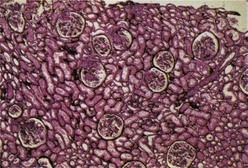

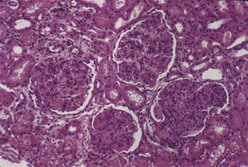

Most investigators consider class III and class IV lupus nephritis to be qualitatively similar glomerular lesions that differ only in severity and distribution. Therefore these two related classes are described together. Class III lupus nephritis is defined as focal segmental and/or global endocapillary and/or extracapillary glomerulonephritis affecting less that 50% of the total glomeruli sampled (Figure 35-3). Class IV is defined as diffuse segmental and/or global endocapillary and/or extracapillary glomerulonephritis affecting 50% or more of the total glomeruli (Figure 35-4). Both class III and class IV manifest subendothelial immune deposits (relatively focal in class III and diffuse in class IV), with or without mesangial alterations. The ISN/RPS classification subdivides lupus nephritis class IV into those cases with diffuse segmental and those with diffuse global proliferation (Table 35-1). The designation IV-S is used if more than 50% of the affected glomeruli have segmental lesions (Figure 35-5); the designation IV-G is used if more than 50% of the affected glomeruli have global lesions (see Figure 35-4). This subdivision was proposed to facilitate future studies addressing possible differences in outcome and pathogenesis among these subgroups.

TABLE 35-1 International Society of Nephrology and Renal Pathology Society Classification of Lupus Nephritis (2004)

| Class I | Minimal mesangial LN |

| Normal glomeruli by LM, but mesangial immune deposits by LF | |

| Class II | Mesangial proliferative LN |

| Purely mesangial hypercellularity of any degree of mesangial matrix expansion by LM with mesangial immune deposits | |

| Possibly a few isolated subepithelial or subendothelial deposits visible by IF or EM but not by LM | |

| Class III | Focal LN* |

| Active or inactive focal, segmental and/or global endocapillary and/or extracapillary GN involving <50% of all glomeruli, typically with focal subendothelial immune deposits, with or without mesangial alterations | |

| Class III (A) | Purely active lesions: focal proliferative LN |

| Class III (A/C) | Active and chronic lesions: focal proliferative and sclerosing LN |

| Class III (C) | Chronic inactive with glomerular scars: focal sclerosing LN |

| Class IV | Diffuse LN* |

| Active and inactive diffuse, segmental and/or global endocapillary and/or extracapillary GN involving ≥50% of all glomeruli, typically with diffuse subendothelial immune deposits, with or without mesangial alterations Divided into diffuse segmental proliferative (IV-S), in which >50% of the involved glomeruli have segmental lesions, and diffuse global proliferative (IV-G), in which >50% of the involved glomeruli have global lesions Segmental is defined as a glomerular lesion that involves less than one half of the glomerular tuft | |

| Class IV-S (A) or IV-G (A) | Purely active lesions; diffuse segmental or global proliferative LN |

| Class IV-S (A/C) or IV-G (A/C) | Active and chronic lesions; diffuse segmental or global proliferative and sclerosing LN |

| Class IV-S (C) or IV-G (C) | Inactive with glomerular scars: diffuse segmental or global sclerosing LN |

| Class V | Membranous LN† |

| Global or segmental subepithelial immune deposits or their morphologic sequelae by LM and by IF or EM, with or without mesangial alterations | |

| Class VI | Advanced sclerosing LN |

| ≥90% of glomeruli globally sclerosed without residual activity |

Definitions of pathologic terms: Diffuse, lesion involving most (≥50%) glomeruli; endocapillary proliferation, endocapillary hypercellularity as a result of an increased number of mesangial cells, endothelial cells, and infiltrating monocytes, causing a narrowing of the glomerular capillary lumina; extracapillary proliferation or cellular crescent, extracapillary cell proliferation of more than two cell layers occupying one fourth or more of the glomerular capsular circumference; focal, lesion involving <50% of glomeruli; global, lesion involving more than one half of the glomerular tuft; hyaline thrombi, intracapillary eosinophilic material of a homogeneous consistency that, by IF, has been shown to consist of immune deposits; karyorrhexis, presence of apoptotic, pyknotic, and fragmented nuclei; mesangial hypercellularity, ≥3 mesangial cells per mesangial region in a 3 µg-thick section; necrosis, lesion characterized by fragmentation of nuclei or disruption of the basement membrane and often associated with the presence of fibrin-rich material; segmental, lesion involving less than one half of the glomerular tuft.

Proportion of involved glomeruli indicates the percentage of total glomeruli affected by lupus nephritis, excluding ischemic glomeruli with inadequate perfusion as a result of vascular pathologic features separate from LGN.

Combination of class III and class V requires membranous involvement of at least 50% of the glomerular capillary surface area of at least 50% of glomeruli by LM or IF.

Combination of class IV and class V requires membranous involvement of at least 50% of the glomerular capillary surface area of at least 50% of glomeruli by LM or IF.

In the report, active lesions have to be specified; the percentage of glomeruli with capillary wall disruption (necrosis) and crescents should be included in the diagnostic line.

EM, Electron microscopy; GN, glomerulonephritis; IF, immunofluorescence, LGN, lupus glomerulonephritis; LM, light microscopy; LN, lupus nephritis.

* Indicates the proportion of glomeruli with active and sclerotic lesions.

Indicates the proportion of glomeruli with fibrinoid necrosis and with cellular crescents.

Indicates the grade (e.g., mild, moderate, severe) tubular atrophy, interstitial inflammation and fibrosis, severity of arteriosclerosis, or other vascular lesions.

† May occur in combination with class III or IV, in which case both will be diagnosed; may show advanced sclerosis.

Hematoxylin bodies are the only truly pathognomonic lesion of lupus nephritis. However, they are extremely uncommon, affecting less than 2% of biopsy specimens of lupus nephritis.22 They consist of smudgy lilac-staining structures that may be smaller or larger than normal nuclei. They may be isolated or clustered and usually occur in glomeruli with very active proliferative and necrotizing lesions. Hematoxylin bodies are the tissue equivalent of the lupus erythematosus body and consist of naked nuclei whose chromatin has been altered after cell death with the extrusion of the nucleus and binding to ambient circulating antinuclear antibodies (ANAs).

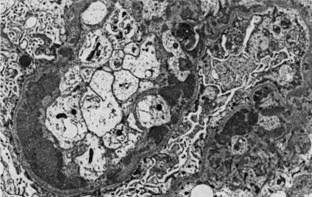

By IF, in class III and IV lupus nephritis, subendothelial immune deposits generally follow the distribution of the endocapillary proliferation. Thus subendothelial deposits tend to be relatively focal and segmental in class III and more diffuse and global in class IV lupus nephritis. These subendothelial deposits are typically superimposed on generalized mesangial immune deposits. Hyaline thrombi form occlusive intracapillary globular deposits. Scattered subepithelial deposits are not uncommon in class III or class IV and usually have a more finely granular quality. However, according to the ISN/RPS classification, the presence of regular subepithelial deposits involving over 50% of the glomerular capillary surface area of at least 50% of glomeruli exceeds what is acceptable in class III or class IV alone and would warrant an additional diagnosis of membranous lupus nephritis class V. By EM, class III and class IV lupus nephritis typically display subendothelial electron-dense deposits that tend to be focal and segmental in class III and more diffuse and global in class IV, superimposed on a substratum of mesangial deposits (Figure 35-6). The extent and distribution of deposits observed by EM usually parallels that visualized with IF. Rare cases of class III or class IV lupus nephritis have relatively sparse subendothelial deposits, relative to the extent and severity of the active necrotizing lesions. Such cases resemble examples of pauci-immune focal segmental necrotizing glomerulonephritis, and some may be associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs).

Class V: Membranous Lupus Nephritis

In the modified WHO classification, membranous lupus nephritis was subdivided into four subclasses, designated Va through Vd. Being familiar with these categories is important, because older outcome studies frequently used these designations. Class Va denotes pure membranous lupus nephritis without associated mesangial deposits or mesangial proliferation. Class Vb includes the typical peripheral capillary wall features of membranous glomerulopathy, together with mesangial alterations, either mesangial deposits alone or with mesangial hypercellularity. The modified WHO classification also recognizes class Vc (combined class Va and class III), in which the typical features of focal and segmental endocapillary proliferative glomerulonephritis are superimposed on the membranous pattern, and class Vd (combined class Va and class IV), in which superimposed diffuse endocapillary proliferative and membranous lupus nephritis is evident. A major disadvantage of this system is that it places undue emphasis on the membranous component rather than on the more serious proliferative component. According to the ISN classification, the designation mixed class III and class V replaces the Vc lesion, and the designation mixed class IV and class V replaces the Vd lesion. In this schema, the additional designation of class V in the setting of class III or class IV requires membranous involvement of at least 50% of glomerular capillary surface area of at least 50% of glomeruli visualized by LM or IF or both. This approach is amply supported by clinical pathologic studies that demonstrate that class Vd has an extremely poor prognosis, even worse than that of pure diffuse proliferative class IV.23

By LM, the peripheral glomerular capillary wall alterations display a spectrum and evolution similar to those of idiopathic membranous glomerulopathy. In the early stages, the glomerular capillary walls may appear normal in thickness and texture by LM, but subepithelial deposits are detected by IF and EM. At this stage, the glomerular capillaries often have a rigid, ecstatic appearance with visceral epithelial cell swelling. Well-established membranous lesions are typically characterized by uniform and diffuse thickening of glomerular capillary walls (Figure 35-7) with well-developed spikes of the GBM that are best demonstrated with the silver stain. As the lesions evolve, the deposits may become largely resorbed and overlaid by neomembrane formation, producing a vacuolated GBM profile.

Epidemiologic Features

The renal criteria for the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) are defined as persistent proteinuria (>0.5 g/day or ≤3+), or cellular casts of any kind24 (see Chapter 1). By these criteria, the prevalence of renal disease in eight large cohort studies consisting of 2649 patients with SLE varied from 31% to 65%.2 Tertiary referral centers tended to have higher percentages of patients with renal disease, as did studies that were published before 1965 (when ANAs became widely available and identified more mild cases of patients with SLE). The mean age at disease onset in patients with nephritis is younger than in those patients with SLE but without nephritis (Wallace and colleagues9 reported disease onset at 4 years younger [27 versus 31 years of age] and 230 versus 379 patients, respectively). Nossent and associates7 also observed a similar difference in 110 patients of Dutch descent. Most patients develop nephritis early in their disease course; the onset of renal disease can occur at any point in the patient’s disease course. Nephritis is present in most children. Although it was once thought rare in older adults, subsequent studies have shown that race confounded the relationship of lupus nephritis with age of onset of disease.25 When race is controlled, patients with older-onset lupus do not have milder features, and the outcome of lupus is worse as a result of the increased prevalence of co-morbidities.26

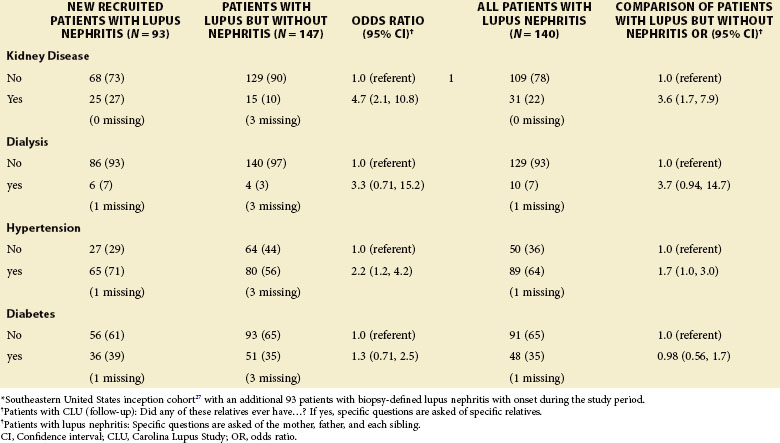

The incidence and prevalence of SLE nephritis differ among patients of different racial and ethnic backgrounds. Despite much investigative attention, these differences in lupus expression remain poorly understood. African Americans have a threefold increased incidence of SLE, develop the disorder at younger ages, more frequently develop nephritis, and more frequently express anti-Smith (anti-Sm) and ribonucleoprotein (RNP) autoantibodies.2 African-American patients develop nephritis earlier in the course of their SLE. In an inception cohort of 265 lupus patients in the southeastern United States, 31% of African-American patients versus 13% of Caucasian patients met ACR renal criteria within 18 months of diagnosis27 (Table 35-2). Patients of Hispanic ethnicity develop nephritis more frequently than Caucasians.28 Once they have nephritis, African Americans and Hispanics are more likely to progress to ESRD than Caucasians.27,28 These findings have also been reported in cohorts based in London and Toronto with National Health Care systems.29,30 Patients of Asian descent also have greater frequency and severity of nephritis compared with Caucasians. However, Asians generally have good outcomes of cytotoxic therapy.31 Patients with lupus and nephritis are more likely than patients without renal involvement to have a family history of diabetes, hypertension, and renal disease (Table 35-3). The annual incidence of nephritis in 384 patients with established lupus followed at the Johns Hopkins Medical Center between 1992 and 1994 was 10%.32

TABLE 35-2 Findings in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and Nephritis (n = 128) Compared with Those without Nephritis (n = 336)*

| MORE FREQUENT | LESS FREQUENT |

|---|---|

| Family history of SLE | Other CNS symptoms |

| Anemia | Seizures |

| High sedimentation rate | Thrombocytopenia |

| High serum cholesterol | Fibromyalgia |

| High serum triglycerides | |

| Positive ANAs | |

| High anti-dsDNA | |

| Low C3 complement | |

| Low C4 complement |

ANAs, Antinuclear antibodies; anti-dsDNA, anti–double stranded DNA; CNS, central nervous system; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

TABLE 35-3 History of Kidney Disease, Hypertension, and Diabetes in First-Degree Relatives (Parents or Siblings)*

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree