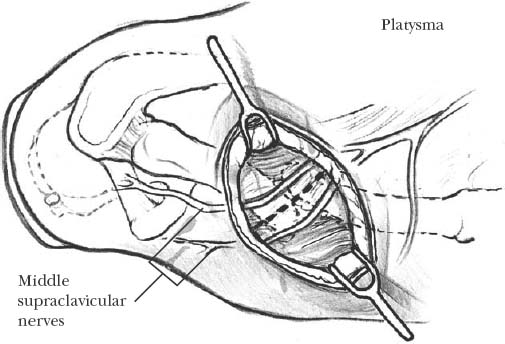

11 The clavicle is truly an elegant and unique bone that functions as the only link between the upper extremity and the trunk. It is the first bone to ossify and is formed via intramembranous ossification.1 Eighty percent of its growth occurs through the medial physis.2 Its blood supply is entirely periosteal.3 The clavicle is composed of an S-shaped double curve, which is firmly attached at its medial and lateral ends.4 The platysma muscle and middle supraclavicular nerves are the only structures to pass superficial to this entire subcutaneous bone. Its cross section varies from being relatively flat laterally to being tubular across its middle section to taking the shape of a prism medially.4,5 Not only does the clavicle function to keep the shoulder in its place, it also contributes to the generation of power and stability of the upper extremity while protecting vital neurovascular structures that pass beneath.6 The clavicle demonstrates mobility at both the stern-oclavicular and acromioclavicular joints.6 The clavicle can rotate on its longitudinal axis about 50 degrees and elevate about 30 degrees when the shoulder is passed through a full range of motion. The acromioclavicular rotation is less than 10 degrees during full shoulder range of motion. The typical clavicular slope is about 12 degrees, and it can move anterior to posterior with protraction and retraction by about 35 degrees.4 Clavicle fractures account for 44% of all shoulder girdle injuries, making up 5 to 15% of all fractures.7,8 In terms of clavicle fractures, 80% involve the middle third, 15% the distal third, and 5% the medial third.9 They can result from high-energy injuries, making them common in young, athletic populations. These fractures result in a fixed, multiplanar deformity demonstrating shortening, inferior, anterior, or rotational displacement. It is generally accepted that clavicular fractures can have effects on the scapula, on the glenohumeral orientation in an anteromedial direction, and on the kinetics of the entire shoulder musculature.10–15 Traditionally, nonoperative treatment has been accepted as the standard of care, likely the result of earlier studies demonstrating unsatisfactory outcomes with operative treatment, as well as a tremendous potential for healing of the fracture by periosteal new bone formation in children.16–18 Nonoperative treatment is not without its associated potential complications and subjective patient dissatisfaction of up to 31% at an average of 3 years postinjury.19–23 These complications consist of a painful prominent callus, prolonged loss from sports activity and sport-specific training, and higher nonunion rates with higher energy fractures.20 Shortening by more than 15 mm may cause chronic pain, weakness, and altered shoulder biomechanics.11,20 Nonoperative treatment may not correct all planes of the deformity, leading to nonunion and even malunion.20 Malunions are associated with poor outcomes because they can contribute to weakness, pain, and neurovascular compromise.11,24 In the past, poor operative results related more to the technique used than the concept of treating these fractures operatively. Various techniques have been tried such as “bumpectomy,” “sculptured” tricortical graft with plate fixation, interposition iliac crest graft with plate fixation, and extension osteotomy.25,26 However, plate and screw fixation is most commonly used. This technique requires extensive soft tissue stripping, which may compromise blood supply to the bone and subsequent healing. It can result in painful, prominent hardware, noncosmetic scars, and chronic stress risers after hardware removal.27 Other techniques that involve smooth pin fixation and external fixation present with possible pin migration and skin problems.28 Recently, the idea has emerged that orthopedic surgeons have not been meeting patient expectations with past clavicle nonoperative treatment. It could be argued that clavicle fractures are the most neglected fractures today because there is no other bone in the body where orthopedic surgeons accept as much deformity or displacement as the standard of care. The senior author has chosen to focus on intramedullary fixation because it minimizes soft tissue dissection, allows the clavicle to shorten naturally, and provides ease of hardware removal. The senior author prefers to use DePuy’s (Warsaw, IN) intramedullary Rockwood clavicle pin for use in the treatment of midshaft clavicle fractures, malunions, and nonunions. This technique helps to remedy the difficulties encountered with past techniques, which include impaired blood supply, painful prominent hardware, and stress risers that are related to the removal of plates and screws. After informed consent is obtained, the patient is taken to the operating room suite and placed in the beach chair position on a radiolucent shoulder-positioning device. An image intensification device or C-arm is needed to facilitate pin placement. The C-arm base is placed in front of the shoulder girdle with the C-arm gantry rotated slightly away from the operative shoulder and oriented with a cephalic tilt. The C-arm is draped into the surgical field with standard split sheets (Figure 11-1). It is important to note that this intramedullary pin placement procedure can be done without C-arm equipment.29 An x-ray cassette can be placed posterior to the shoulder prior to prepping and draping. X-rays can then be taken throughout the procedure to verify pin position. FIGURE 11-1. C-arm setup with the patient in beach chair position. The C-arm is draped into the surgical field. Often the arm of the machine needs to be angled across the patient toward the midline. A 3 cm incision in Langer’s lines over the distal end of the medial fragment is made (Figure 11-2). This is done because the clavicle skin can be moved more easily in a medial direction. Most patients have a deep skin crease in the area of the skin incision. This placement results in a more cosmetically pleasing scar. FIGURE 11-2. A longitudinal incision is made over the lateral aspect of the medial fragment of the fracture. The incision is often parallel to the skin crease, making for a cosmetically pleasing scar. Care should be taken to dissect out the middle supraclavicular sensory nerve branches. Care must be taken to prevent injury to the underlying platysma muscle. Use of scissors to free the platysma from the overlying skin must be done carefully because there is little subcutaneous fat in this region. Take care to prevent injury to the middle branch of the supraclavicular nerve, which is usually found directly beneath the platysma muscle near the midclavicle. Identification and retraction of the nerve are performed to prevent injury to the nerve (see Figure 11-2). It has been the senior author’s experience that there will be interposed muscle and soft tissue at the fracture site. This interposed tissue is carefully removed with an elevator or curette. All small butterfly fragments that are still attached to their soft tissue envelope are left in place. These fragments are usually anterior in the dissection field. The proximal end of the medial clavicle is elevated through the incision with a towel clip, elevator, or bone-holding forceps (Figure 11-3). The smooth ends of the taps or drills are used to size the canal, usually 10 to 12 mm. Taking care not to penetrate the anterior cortex, the surgeon attaches the appropriately sized drill to the ratchet T handle and drills the intramedullary canal (Figure 11-4). The fit should not be too loose or too tight, as this may compromise fixation or split the bone, respectively. Orientation of the drill should be checked with the C-arm. The drill is removed from the medial fragment. Then, the appropriately sized tap is attached to the T handle, and the intramedullary canal is tapped to the anterior cortex (Figure 11-5).

Clavicle Fractures, Malunions, and Nonunions

Incidence

Treatment

Nonoperative Treatment

Operative Treatment

Indications

Patient Positioning and Setup

Skin Incision

Drilling and Tapping of the Intramedullary Canal

Clavicle Fractures, Malunions, and Nonunions

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree