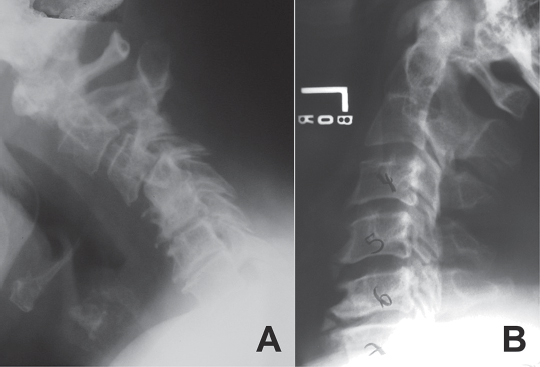

19 Myelopathy is a constellation of symptoms resulting from spinal cord dysfunction due to compression on the spinal cord. Symptoms are often vague and tend to progress over time. The spinal cord can be compressed from anterior structures, such as disk herniations or osteophytes, or from posterior structures, including the facet joints and ligamentum flavum. While mild cases can be treated with observation, most cases require surgical decompression. Anterior, posterior, and combined approaches can be used depending on the location of the compression, extent of disease, number of levels involved, posture of the cervical spine, and other patient and disease related factors. In its normal state, the cervical spine is in lordotic posture as a result of the anterior disk height being slightly greater than the posterior disk height. The disk functions to dissipate the energy of vertical forces, but with aging it sustains weakening of the annular fibers, leading to posterior protrusion, loss of disk height, and redundancy of the ligamentum flavum, which encroaches on the spinal canal and decreases the space available for the spinal cord. In addition, decreased disk height can lead to loss of the normal lordotic curvature and development of a kyphotic posture. This causes the spinal cord to be further draped over anterior structures and can lead to increased pressure on the cord. Biomechanically, disk degeneration transfers stress to the vertebral end-plates, resulting in the formation of osteophytes along the margins of the disk space and behind the uncovertebral joints. By age 50, at least half of patients will have radiographic evidence of spondylosis. Although most will remain asymptomatic, in some individuals these may contribute to further compression of the spinal canal. Cervical myelopathy is graded from 0 to V using the Nurick classification. This classification takes ambulatory ability into account in determining the grade (Table 19.1). Symptoms of cervical spondylotic myelopathy are often vague and may include neck pain or stiffness, numbness and tingling, loss of fine finger dexterity, and gait disturbances. Changes in dexterity may manifest as difficulty buttoning shirts or manipulating small objects and/or changes in handwriting. Patients may complain of gait unsteadiness and may appear to have a wide-based or waddling style of gait. In severe cases, bowel and/or bladder function may be affected. Clinical findings in myelopathy often include a wide-based gait, difficulty with tandem gait, upper and/or lower extremity weakness, hyperreflexia, intrinsic hand muscle wasting, and the presence of abnormal reflexes, such as Babinski reflex, Hoffmann sign, inverted radial reflex, ulnar escape sign, and ankle clonus. Initial radiographic assessment begins with evaluation of plain radiographs, including anteroposterior (AP), lateral, and flexion-extension lateral views (Fig. 19.1A,B). Observed changes may include spondylosis, loss of lordosis, or subluxations. Patients with symptoms of myelopathy require advanced imaging, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) myelogram, to assess compression of the spinal cord. MRI is generally ordered first because it is noninvasive and demonstrates cord compression and changes in spinal cord parenchyma (Fig. 19.2). Increased signal intensity in spinal cord parenchyma on T2 images may represent spinal cord edema and/or myelomalacia and is considered to be a sign of significant compression. Table 19.1 The Nurick Classification

Cervical Myelopathy: Anterior Approach

![]() Classification

Classification

![]() Workup

Workup

Grade 0 | Root signs and symptoms, no cord involvement |

Grade I | Signs of cord involvement, normal gait |

Grade II | Mild gait involvement, able to be employed |

Grade III | Gait abnormality prevents employment |

Grade IV | Able to ambulate only with assistance |

Grade V | Chair-bound or bedridden |

Fig. 19.1 (A) Flexion plain radiograph demonstrating instability in a severely spondylotic cervical spine with motion. (B) Extension plain radiograph showing osteophytes located on the posterior surface of the vertebral bodies, illustrating how they can lead to compression of the spinal cord.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree