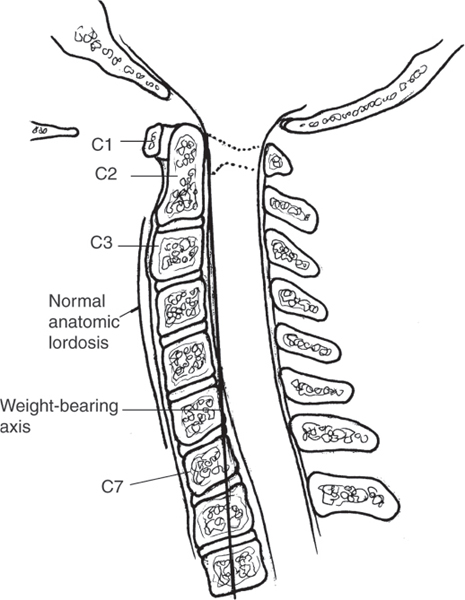

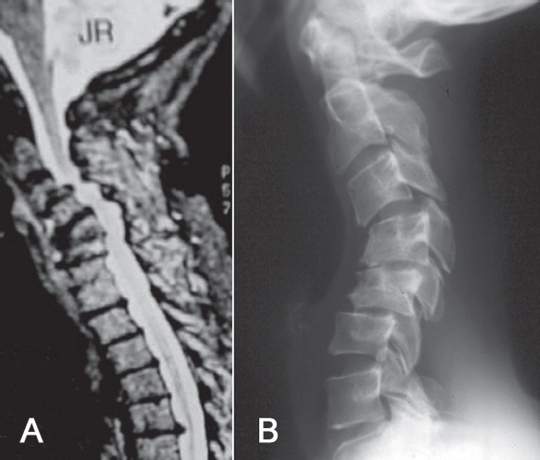

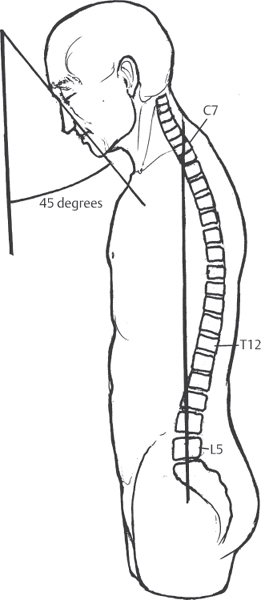

21 Lordosis is the normal cervical posture, with the weight-bearing axis falling posterior to the vertebral bodies of C3 to C7, and this posture is important for proper head positioning and horizontal gaze. In the normal state, nearly two-thirds of the compressive load of the neck is borne by the posterior elements (Fig. 21.1). Certain conditions result in progressive loss of cervical lordosis and may lead to kyphosis. Examples of such conditions include cervical spondylosis, cervical trauma, cervical laminectomy, ankylosing spondylitis (AS), and diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH). Cervical kyphosis is best classified as degenerative, post-traumatic, iatrogenic, or related to spondylarthropathy (AS/DISH) (Fig. 21.2). Degenerative kyphosis occurs because of sequential loss of disk height, which makes up around 15% of anterior column height in the normal cervical spine. Loss of intervertebral height leads to loss of cervical lordosis, shifting the compressive load from the posterior to the anterior column, and ultimately results in a kyphotic alignment. Traumatic injury may result in anterior column compression, posterior element tension failure, or both. Iatrogenic kyphosis most often occurs following a cervical laminectomy and is more common in the setting of underlying preoperative kyphosis or in the immature spine. Kyphosis related to spondylathropathy occurs as the spine ossifies and stiffens, shifting the weight-bearing axis anteriorly and leading to a progressive sagittal imbalance. Fig. 21.1 The weight-bearing axis should fall posterior to the vertebral bodies of C3–C7 because of the normal anatomic lordosis of the cervical spine. Evaluation of cervical kyphosis requires a thorough history to elucidate the cause of deformity, such as personal or family history of a spondylarthropathy or symptoms suggestive of an undiagnosed spondylarthropathy, history of cervical laminectomy, or neck and/or arm pain consistent with degenerative disease. Fig. 21.2 (A) Sagittal MRI shows degenerative kyphosis with loss of the disk height. (B) Lateral plain radiograph of postlaminectomy kyphosis resulting from an overly aggressive facet resection with decreased posterior column stability. Examination should include assessment of the gross alignment of the head and neck, the degree of forward tilt, the degree of flexibility of the deformity, and the presence of radiculopathy or myelopathy. Sagittal alignment should be characterized by viewing the standing patient from the side, and photographs may be helpful for surgical planning. Range-of-motion testing in extension, flexion, side bending, and rotation helps to define a rigid or fixed deformity. Evaluation of the nerve roots and spinal cord requires motor, reflex, and sensory testing of the C3–T1 nerves. Special tests necessary to rule out “upper tract signs” include Romberg sign, Babinski reflex, and Hoffmann sign, which may be associated with spinal cord compression. Imaging should include anteroposterior (AP), lateral, flexion/extension, and oblique radiographs, with careful attention paid to sagittal alignment, evidence of instability on the flexion/extension views, and facet ankylosis (best seen on oblique views). In patients with AS who present with cervical kyphosis, an entire-spine lateral radiograph that includes the head will enable measurement of the chin-brow vertical angle (Fig. 21.3), which quantifies the overall kyphosis of the head on the torso and is useful in planning reconstructive surgery. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) helps to assess alignment, nerve or spinal cord compression, and signal change within the spinal cord (Fig. 21.4). Patients with DISH should be evaluated for the presence of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Computed tomography (CT) best demonstrates this ossification; post-myelogram CT is highly useful in defining cord compression due to ossification. Similarly, CT scan is often beneficial in defining fracture anatomy after cervical trauma. In certain special situations, vertebral artery characterization may be necessary via conventional angiography or magnetic resonance (MR) arteriography to plan the surgical approach for decompression and instrumentation. Fig. 21.3 The chin-brow vertical angle is used to measure the overall kyphosis of the head on the torso. It is calculated by drawing one line from the eyebrow to the chin and a second line vertically, and then measuring the angle formed by the intersection of the two lines.

Cervical Kyphosis

![]() Classification

Classification

![]() Workup

Workup

History

Physical Examination

Spinal Imaging

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree