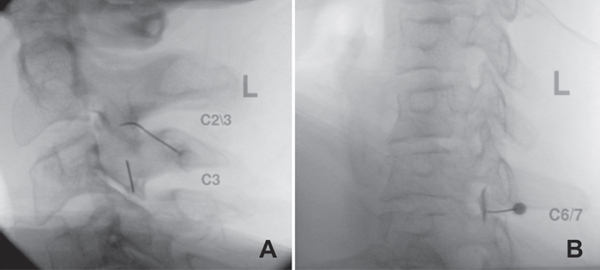

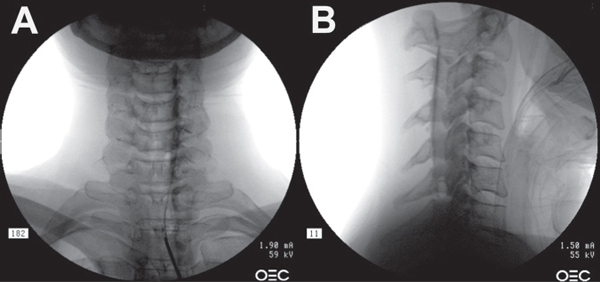

24 Chronic neck pain in the adult general population has 26% to 71% lifetime prevalence, contributing to significant socioeconomic impact. The etiology of neck pain is complex. To ensure accuracy in the diagnosis and in the selection of appropriate treatment, it is recommended to use an algorithmic approach with correlation between history, physical exam, imaging tests, and confirmatory diagnostic or therapeutic procedures. It is important to exclude nonspinal causes, rheumatologic disease, infection, and tumor as well as cord compression (myelopathy or large disk herniations) in the early stages. Differential diagnosis should also exclude proximal compression of the brachial plexus (as with thoracic outlet syndrome) or distal nerve compression caused by entrapment syndromes that can mimic root compression, as well as the shoulder complex. Once other sources of pain have been mostly eliminated from the differential diagnosis, structure-specific spine injections may help to establish diagnosis in over 80% of cases and may significantly increase the efficacy of treatment. Chronic axial neck pain related to cervical zygapophyseal (facet) joints and supporting capsules may account for 36% of patients, with prevalence increasing to 60% after a whiplash-type injury. Imaging tests and clinical examination, including localized pain during palpation and increase in neck pain with extension, are not very specific and reliable. There are two diagnostic procedures available to confirm the diagnosis: one is intra-articular facet joint injection, which can be associated with potentially higher neurovascular complications, and another is a medial branch block (MBB). MBB is an indirect but simple and safe way of assessing facet joint–mediated pain, with a low (3.9%) rate of inadvertent intravascular penetration reported. In order to block pain from one facet joint, at least two medial branches have to be anesthetized. Because of high false-positive rates (38%) with uncontrolled MBBs, patients who respond initially to blocks with lidocaine should subsequently undergo confirmatory blocks with bupivacaine. Complete or definite (> 80%) relief of pain following a block of two adjacent medial branches identifies the symptomatic joint (Fig. 24.1A). Partial relief may mean that the blocked joint is not painful and that the adjacent joint that was partially blocked is symptomatic, or it could mean that the blocked joint is symptomatic but another joint or a different structure is also symptomatic. Some reports describe prolonged pain relief after MBBs with moderate evidence for therapeutic utility. Therapeutic approaches include intraarticular facet injection of corticosteroid (Fig. 24.1B) combined with local anesthetic, especially with acute pain or when intraarticular inflammation is suspected. Although not validated in the general patient population, older patients often have chronic pain secondary to intraarticular inflammation, and therapeutic corticosteroid facet joint injections can be used on an occasional basis for pain control. Another common treatment modality is radiofrequency neurotomy (RFN). In this procedure, a Teflon-coated electrode with an exposed tip is inserted close to and parallel to a medial branch of a spinal nerve, and a high-frequency electrical current is applied to the electrode with concentration around the exposed tip, heating and coagulating the immediately surrounding tissue, including the target nerve. RFN is not a permanent treatment, and the medial branch nerves will usually regenerate in 6 to 18 months, but the procedure can be repeated if necessary. It has been reported that repeated procedures provide equal effectiveness for a mean duration of 10 months. Alternative approaches include pulsed radiofrequency, with less than 42°C temperature at the tip of the electrode applied in a pulsed manner to a medial branch, which may decrease pain for several months with no well-established mechanism of action. However only RFN at 80°C showed positive outcomes in randomized controlled trials in well-selected patients. Since neurotomies are considered to be palliative procedures, some physicians advocate the injection of hypertonic solutions into the ligamentous structures of the posterior column, theoretically to promote both added tissue desensitization and connective tissue repair, or injections of “restorative solutions.” Fig. 24.1 (A) Fluoroscopy showing a facet injection at C2–C3 and medial branch block at C3. (B) Fluoroscopy showing a transforaminal epidural steroid injection at C6–C7. Middle column pain is typically a result of inflammation or epidural and dural tissue irritation. It can be a result of static/dynamic stenosis, protruding or herniated disks, uncinate osteophytes with neuroforaminal stenosis, postlaminectomy syndrome, or nerve root inflammation. In most cases the structural abnormalities can be seen on a cervical magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan, and once they correlate with the clinical presentation consistent with middle column structure inflammation or nerve root compression, a therapeutic epidural injection of corticosteroids can be performed as a primary interventional procedure. Diagnostic accuracy of cervical selective nerve root blocks has not been established. Although the transforaminal approach (Fig. 24.2A) is the most selective route for delivering local anesthetic and corticosteroids to the site of inflammation, it has been associated with substantial risk. This approach has become controversial, because injection of particulate corticosteroids into the vertebral artery can cause cerebellar infarcts, and injection into a radicular artery can cause cord infarction. Neurologic complications, which have been discussed in several recent review articles, can be minimized with the use of nonparticulate steroids, injection of a test dose bolus of short-acting local anesthetic, use of live digital subtraction fluoroscopy, and avoidance of excessive sedation. Many interventionalists currently prefer the interlaminar route using a single-needle technique because the risk of injecting into the vertebral or radicular artery is remote (Fig. 24.2B). However, injection into the spinal cord or compression of the spinal cord by a hematoma or abscess may rarely occur. These injections should not be performed at a stenotic level or at a level with a significant central disk protrusion. Most practitioners prefer a single-needle interlaminar approach through the ligamentum flavum at the C7–T1 or T1–T2 levels. Some interventionalists will perform the injection at higher levels, although they are associated with a higher risk because of the presence of anatomic gaps in the ligamentum flavum in the midline, which are more common at the upper cervical levels. Using the upper-level approach, one should closely monitor the lateral as well as the anteroposterior (AP) fluoroscopy view and make sure the needle does not pass forward of the interspinous line. A growing number of interventionalists use an epidural catheter via interlaminar access at the T1–T2 level to reach a site of structural cervical pathology at levels above. This techique is considered to be safer because of the wider distance from the ligamentum flavum to the dural sac (0.5 cm) and from the ligamentum flavum to the spinal cord (1.0 cm). Fig. 24.2 Interlaminar epidural steroid injection with catheter at right C6–C7. (A) Anteroposterior view. (B) Lateral view.

Cervical Diagnostic and Therapeutic Injections and Procedures

![]() Posterior Column

Posterior Column

![]() Middle Column

Middle Column

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree