25

Cannulation Injuries

Leon S. Benson

History and Clinical Presentation

The hand surgery service was called to evaluate the thumb and index finger of a 75-year-old woman. The patient had been admitted to the hospital 1 week previously for heart failure. Twenty-four hours after admission she became increasingly hypotensive and was transferred to the intensive care unit. A Swan-Ganz catheter was placed, the patient was intubated, and a left wrist arterial line was inserted. On hospital admission day 7, the patient was still in the intensive care unit and intubated but she was slowly improving. However, it was then noted that her thumb and index finger, which had looked “dusky” on the previous day, were now turning black and rigid (Figs. 25–1 and 25–2) even though the radial artery catheter had been removed on the previous day.

Physical Examination

Examination of the left hand demonstrated dry gangrene of the thumb that was sharply demarcated distal to the midportion of the proximal phalanx. The left index finger also demonstrated dry gangrene, although a more gradual zone of transition was present, with grossly necrotic tissue being present circumferentially distal to the distal interphalangeal joint. No other soft tissue compromise was noted about the hand. A normal ulnar pulse was easily palpable at the wrist, whereas a radial pulse was undetectable, either by palpation or Doppler examination. A small puncture wound and 3-cm ecchymotic area were present where the radial pulse normally would have been palpable. Nursing staff noted that this was the site of arterial line placement when the patient was first admitted to the intensive care unit. The line, which was an 18-gauge angiocatheter, had been removed 2 days earlier when it seemed to be dysfunctional.

Figure 25–1. Clinical presentation of the volar surface with a black and rigid appearance with sharp demarcation demonstrating dry gangrene.

Figure 25–2. Clinical presentation of the dorsal surface with a black and rigid appearance with sharp demarcation demonstrating dry gangrene.

Diagnostic Studies

Plain radiographs of the distal radius, wrist, and hand demonstrated no acute bony abnormalities. Upper extremity angiography was performed later in the patient’s hospital stay, and complete occlusion of the radial artery was demonstrated just proximal to the wrist. Furthermore, the ulnar artery was shown to provide little blood flow to the radial side of the hand. Some collateral flow was present coming from the ulnar arch, although no large vessels could be seen extending to the distal portion of the thumb or index finger.

PEARLS

- Up to 20% of patients have an incomplete ulnar arterial arch in which the thumb and index fingers are completely dependent on the radial artery for blood flow.

- The timed Allen’s test is the simplest and cheapest way to accurately screen for patients with incomplete arterial arch anatomy.

- Twenty-gauge Teflon catheters are associated with less thrombosis production in the radial artery than larger (18-gauge) heparin-coated polyethylene catheters.

- Constant irrigation of the catheter greatly reduces thrombus formation.

- Allen’s test is inconclusive if blushing of the hand is delayed for 10 to 15 seconds.

- The overall incidence of radial artery thrombosis after cannulation has been estimated to ∼10 to 25%.

- If prolonged arterial monitoring is required, the temporal artery is a good choice. It is totally expendable and can easily be used for 5 to 7 days without clotting. Access can be achieved with a small incision under local anesthesia.

- Pretreating the patient with a single, 600-mg dose of aspirin has been shown to diminish the frequency of radial artery thrombosis from cannulation (without any associated bleeding complications).

PITFALLS

- Any sign of vascular compromise to the hand should be evaluated immediately. Amputation of digits is frequently the only treatment option available because ischemia is not noticed until tissue necrosis has occurred.

- Forcible extension of the digits or hyperextension of the wrist can produce blanching, causing a false-positive Allen’s test.

- At least 11 pounds of pressure are required to occlude the radial or ulnar artery at the wrist when performing an Allen’s test.

- Allen’s test must be modified when it is performed in unconscious patients. To perform the test for these patients, hand ischemia can be temporarily induced using an Esmarch bandage, and a reflow to the palmar arches can be assessed using a Doppler ultrasound device.

- Catheters that are not irrigated will reliably produce radial artery thrombosis if left in place for more than 40 hours. Most authors recommend leaving the catheter in place for no more than 12 to 18 hours.

- Pulse oximetry may provide normal values in the face of significantly compromised blood flow to the digits. It is therefore less valuable in identifying critical ischemia to the digits.

- When a radial artery catheter is in place, it should not be ignored. The site should be examined periodically. Circumferential bandages (including hospital identification bracelets) should be removed, and hypotension, vasoconstrictive drugs, and hypothermia should be avoided if at all possible. Any signs of ischemia or inflammation, such as redness at the site, loss of capillary refill or normal tissue color distally, or change in pulses in the wrist or palm, should prompt immediate removal of the catheter. Any failure of local changes to reverse within 1 hour should make surgical exploration of the artery a serious consideration.

- Up to 30% of thrombi may form a day or more after the catheter is removed from the radial artery. Therefore, careful observation for hand ischemia must be pursued for several days after the catheter is removed.

Differential Diagnosis

Radial artery thrombosis due to cannulation injury

Embolic thrombosis of digital vessels

Small vessel occlusion due to diabetes or a vasculitic disease

Digital ischemia as a side effect of pharmacologic blood pressure support (e.g., Neo-Synephrine related vasoconstriction)

Localized severe infection

Diagnosis

Radial Artery Thrombosis Due to Cannulation Injury in a Patient with Radial Dominant Flow to the Hand

Vascular complications due to cannulation or injection injuries can be devastating. It is important to know how radial artery cannulation injury occurs, not only because of the high frequency of radial artery use for placement of monitoring catheters, but also because of the extreme consequences of radial artery damage in select individuals.

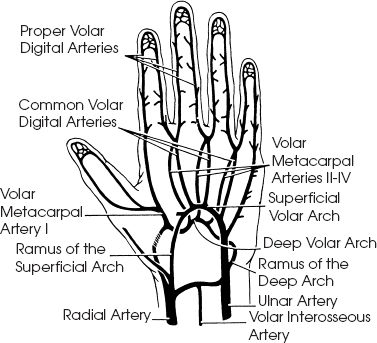

Understanding the arterial anatomy of the hand is key in accounting for cannulation injury. There are two main arches that support vascularity to the digits: the superficial palmar arch, which is an extension of the ulnar artery, and the deep palmar arch, which generally arises from the radial artery (Fig. 25–3). The superficial (ulnar) arch, which is slightly more distal and palmar than the deep arch (radial arch), is the primary blood supply to the ulnar three digits through its connections with the volar digital arteries. The deep arch comes off the radial artery, where this vessel drops down through the anatomic snuffbox and branches into the princeps pollicis artery (to the thumb). This large vessel to the index finger terminates at the deep palmar arch. In the usual circumstance, both arches connect to each other. The ulnar arch often terminates as a smaller diameter vessel that connects to a superficial branch of the radial artery, and the deep radial arch usually terminates in the ulnar palm by connecting to the ulnar arch via collateral vessels. There can be, however, great variability in the specific vascular networking within any given hand. For example, the median artery, which is present in fetal development, can occasionally persist as a major vessel and contribute additional blood flow to the two main arches. More importantly, the two main arches may exist as “incomplete” patterns, in which there are minimal connections between the radial and ulnar derived vascular trees in the palm. It is thought that an incomplete ulnar arch exists in ∼20% of hands, and in this scenario the thumb and index finger derive most, if not all, of their blood supply from the radial artery (Fig. 25–4).