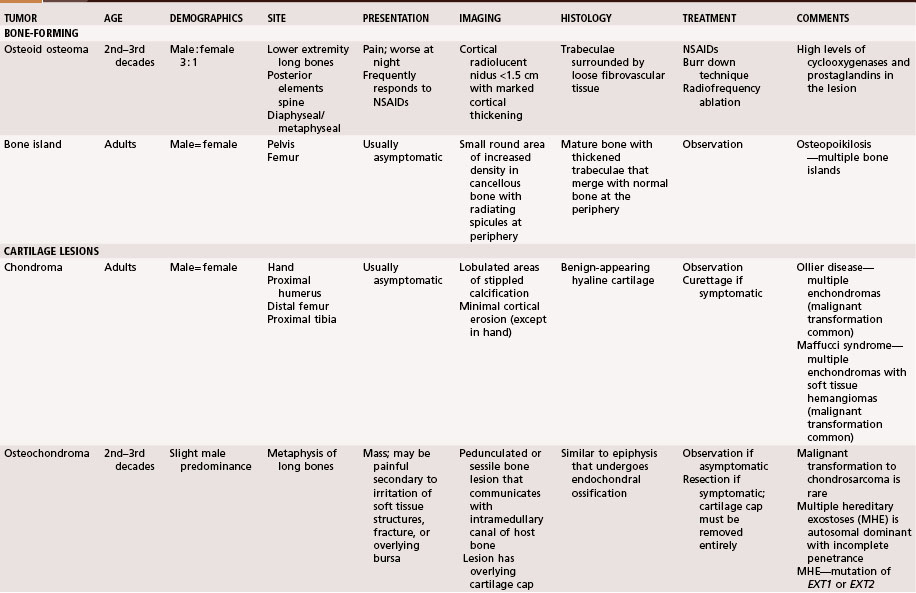

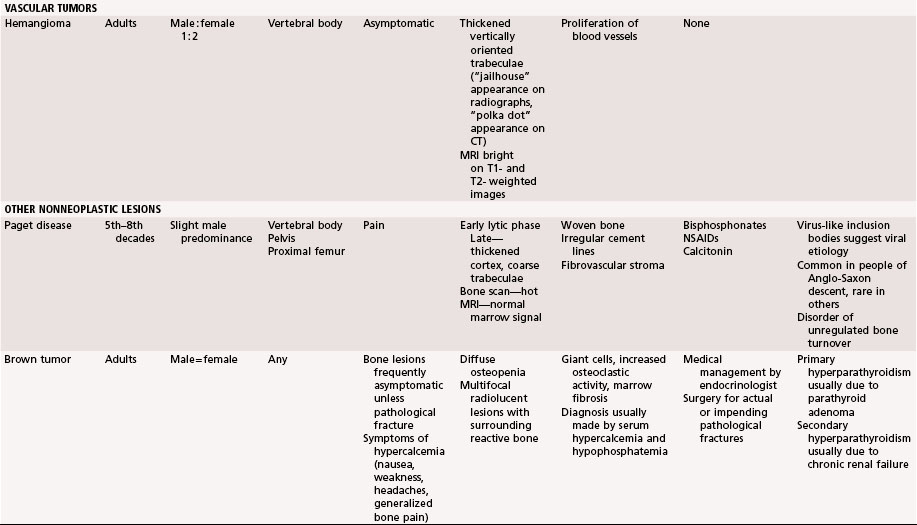

Chapter 25 Benign Bone Tumors and Nonneoplastic Conditions Simulating Bone Tumors

This chapter discusses bony lesions that usually do not behave aggressively locally and that have never been shown to metastasize. Most are either asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic except when complications, such as a pathological fracture, occur. Many are discovered incidentally (Table 25-1).

Bone-Forming Tumors

Osteoid Osteoma

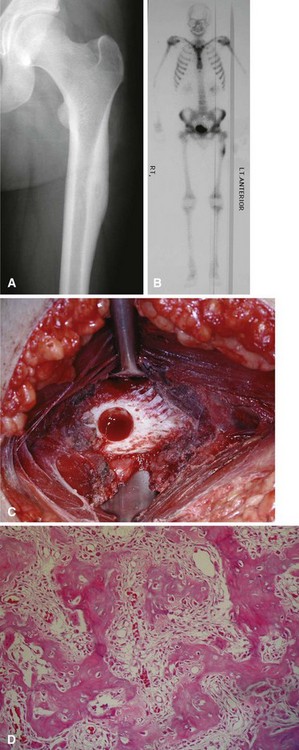

The microscopic appearance consists of fibrovascular tissue with immature bony trabeculae that are rimmed by prominent osteoblasts. The appearance is similar to that of an osteoblastoma with the exception that osteoblastomas are larger. The lesion usually is surrounded by a sclerotic rim. There is no nuclear atypia. Osteoclasts and occasional giant cells can be seen. There are no aggressive features (Fig. 25-1).

Most patients with lesions of the pelvis or long bones of the extremities can be treated with percutaneous radiofrequency ablation (Fig. 25-2). This technique involves a CT-guided core needle biopsy after which a radiofrequency electrode is inserted through the cannula of the biopsy needle. The temperature at the tip is increased to 90°C for 6 minutes. Multiple authors have reported excellent results with this procedure. It usually is done as an outpatient procedure, and patients usually can return immediately to full activity. Recurrence rates are less than 10%. The procedure may not be indicated for vertebral lesions (due to risk of thermal injury to the spinal cord) or lesions of the small bones of the hands or feet (due to risk of thermal injury to the skin).

Bone Island

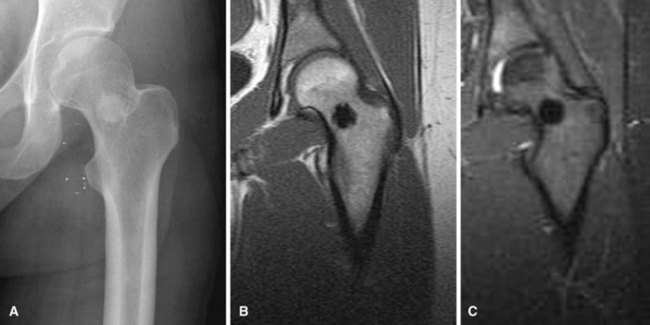

Bone islands usually can be diagnosed by plain radiographs. They typically are small, round or oval areas of homogeneous increased density within the cancellous bone (Fig. 25-3A). Radiating spicules on the periphery of the bone islands merge with the native bone creating a brushlike border. No bony destruction or periosteal reaction is noted. They may show mildly increased uptake on bone scans; however, markedly positive scans should raise suspicion of more aggressive lesions. CT scans show thickened trabeculae that merge with the surrounding bone. MRI usually shows well-defined lesions that are isointense to cortical bone and thus dark on T1- and T2-weighted images (Fig. 25-3B and C) with no surrounding edema. There are no aggressive imaging features.

Cartilage Lesions

Chondroma

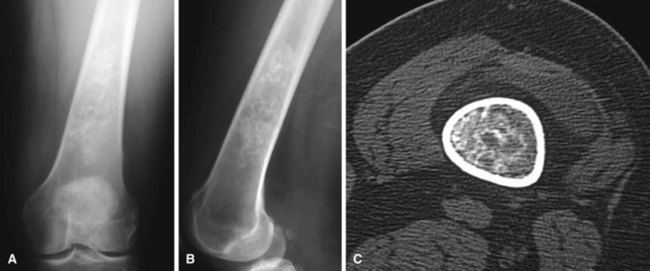

Radiographically, enchondromas are benign-appearing tumors with intralesional calcification (Fig. 25-4A and B). The calcification is irregular and has been described as “stippled,” “punctate,” or “popcorn.” In the small bones of the hands and feet there may be considerable erosion and expansion of the overlying cortex. In more proximal locations (e.g., the pelvis, proximal humerus, or proximal femur), deep endosteal erosion (two thirds of the thickness of the cortex) frequently indicates a chondrosarcoma. An associated soft tissue mass is never present with an enchondroma and always indicates a chondrosarcoma. Juxtacortical chondromas usually are small (<3 cm), well-defined lesions that frequently appear to fit in a saucer-shaped defect on the surface of the bone (Fig. 25-5). The underlying cortex appears sclerotic, and the edges of the lesion appear to be buttressed by a thick rind of cortical bone. Plain radiographs usually are sufficient to diagnose a chondroma. If the diagnosis is in question, CT is best to evaluate endosteal erosion that could indicate a chondrosarcoma (see Fig. 25-4C).

FIGURE 25-5 Anteroposterior radiograph of left proximal humerus of 18-year-old man with a juxtacortical chondroma.

Treatment of patients with solitary enchondromas usually consists of observation with serial radiographs. If the lesion remains radiographically stable and asymptomatic, no further intervention is indicated. If a lesion grows, or if it becomes symptomatic, extended curettage usually is curative. Before recommending surgery for a symptomatic lesion, however, all efforts should be made to rule out other possible sources of the patient’s pain (e.g., rotator cuff tear in a patient with a proximal humeral enchondroma) (Fig. 25-6). Recurrence rates are low. Treatment of patients with multiple enchondromatosis can be more difficult. Although the individual lesions usually are not treated, the more obvious deformities can be corrected by osteotomy. These patients also must be monitored indefinitely for malignant change.

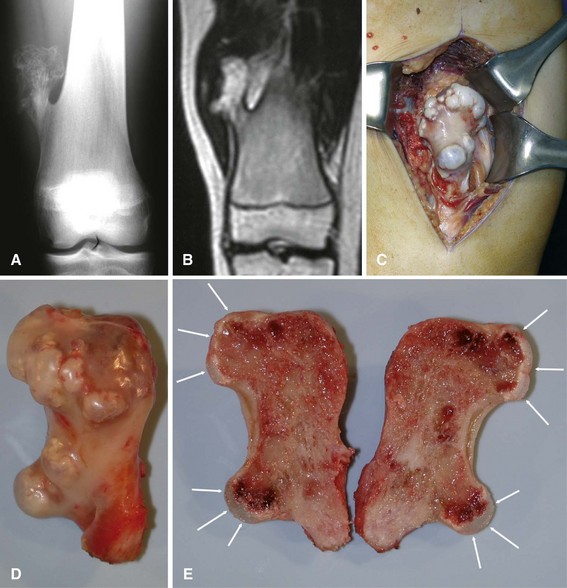

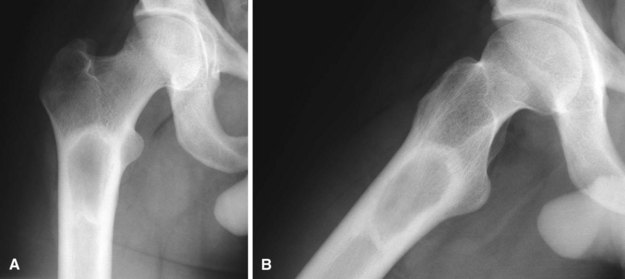

Osteochondroma

Osteochondromas are common benign bone tumors. They probably are developmental malformations rather than true neoplasms and are thought to originate within the periosteum as small cartilaginous nodules. The lesions consist of a bony mass, often in the form of a stalk, produced by progressive endochondral ossification of a growing cartilaginous cap. In contrast to true neoplasms, their growth usually parallels that of the patient and usually ceases when skeletal maturity is reached. Most lesions are found during the period of rapid skeletal growth. About 90% of patients have only a single lesion. Osteochondromas may occur on any bone preformed in cartilage but usually are found on the metaphysis of a long bone near the physis (Fig. 25-7). They are seen most often on the distal femur, the proximal tibia, and the proximal humerus. They rarely develop in a joint. Trevor disease (dysplasia epiphysealis hemimelica) refers to an intraarticular epiphyseal osteochondroma. When multiple joints are involved, it is usually unilateral (hemimelica).

Multiple hereditary exostoses is an autosomal dominant condition with variable penetrance. Most patients with this disorder have a mutation in one of two genes: EXT1, which is located on chromosome 8q24.11-q24.13, or EXT2, which is located on chromosome 11p11-12. In this disease, osteochondromas of many bones are caused by an anomaly of skeletal development. The most striking feature is the presence of many exostoses (Fig. 25-8), but disturbances in growth also occur, such as abnormal tubulation of bones, producing broad and blunt metaphyses, and sometimes bowing of the radius and shortening of the ulna, producing ulnar deviation of the hand. The disease occurs only 5% to 10% as often as solitary osteochondroma and is more common in males. It usually is discovered at about the same age as the solitary lesion, but closer examination of children in families with the disease might lead to earlier discovery.

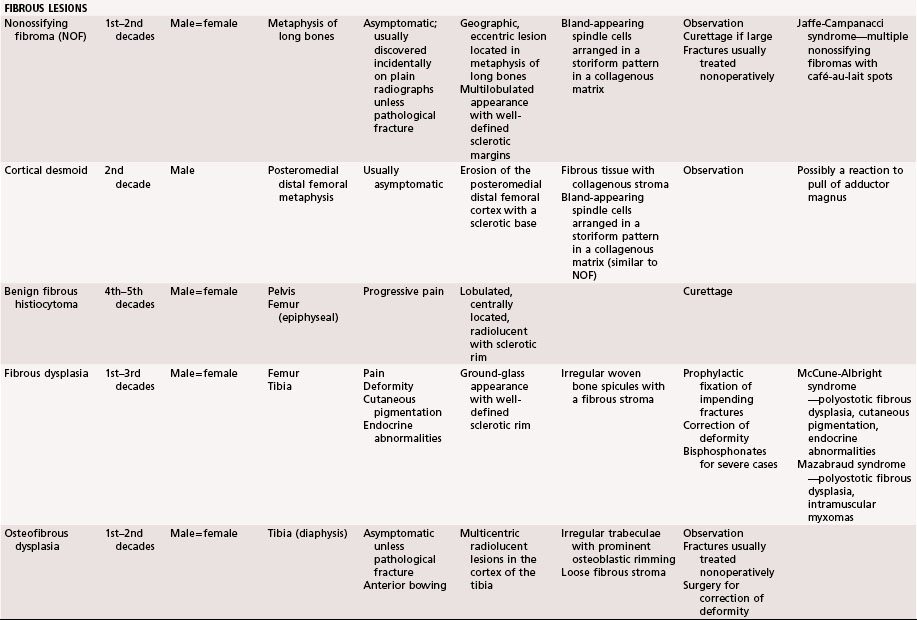

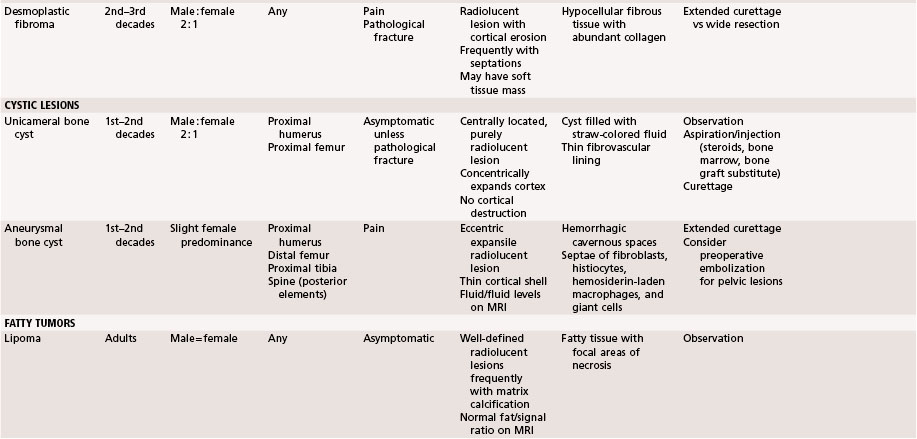

Fibrous Lesions

Nonossifying Fibroma

Nonossifying fibromas (also known as metaphyseal fibrous defects, fibrous cortical defects, and fibroxanthomas) are common developmental abnormalities and are believed to occur in 35% of children. Usually they are found incidentally. Generally, these lesions occur in the metaphyseal region of long bones in individuals 2 to 20 years old. Although any bone may be involved, approximately 40% of these lesions are found in the distal femur, 40% in the tibia, and 10% in the fibula. On plain radiographs, a nonossifying fibroma appears as a well-defined lobulated lesion located eccentrically in the metaphysis (Fig. 25-9). Multilocular appearance or ridges in the bony wall, sclerotic scalloped borders, and erosion of the cortex are frequent findings. There is no periosteal reaction in the absence of a pathological fracture.

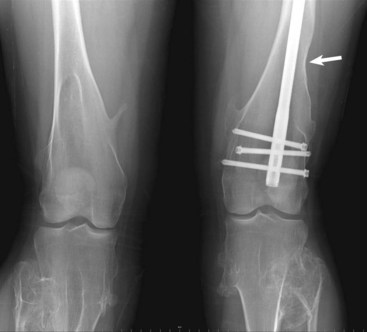

Most nonossifying fibromas are asymptomatic and regress spontaneously in adulthood. Most pathological fractures can be treated nonoperatively. Lesions may become symptomatic and require treatment if they become large or if they are subjected to repeated trauma. Some authors have recommended treatment for lesions that are larger than 50% of the diameter of the bone because of a theoretical increased risk of pathological fracture, although this parameter is not universally accepted as an indication for surgery. Recurrence after curettage is rare (Fig. 25-10).

Cortical Desmoid

A cortical desmoid is an irregularity in the posteromedial aspect of the distal femoral metaphysis and usually is seen in boys 10 to 15 years old. It may be a reaction to muscle stress exerted by the adductor magnus. The lesion is best seen on an oblique radiograph made with the lower extremity externally rotated 20 to 45 degrees. Clinical symptoms, if any, include soft tissue swelling and pain. Radiographs and MRI reveal erosion of the cortex with a sclerotic base (Fig. 25-11). A biopsy is not warranted. Treatment usually consists of observation.

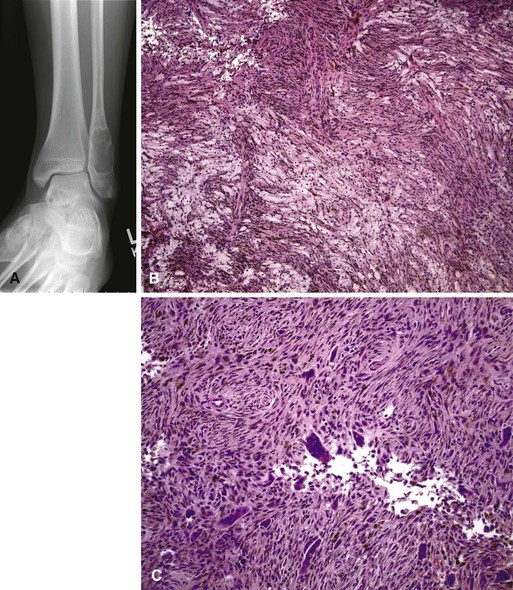

Benign Fibrous Histiocytoma

Benign fibrous histiocytoma is a rare entity that was first described by Dahlin in 1978. This lesion occurs most frequently in the soft tissues and is less common in bone. Although it is histologically similar to nonossifying fibroma, it is a much more aggressive tumor in its biological behavior and radiographic characteristics (Fig. 25-12). In contrast to nonossifying fibroma, which usually is an eccentric metaphyseal lesion, benign fibrous histiocytoma may occur in the diaphysis or epiphysis of long bones or in the pelvis. It is distinguished further by its occurrence in older patients between the ages of 30 and 40 years. Radiographically, benign fibrous histiocytoma is a well-defined, lytic, expanding lesion with little periosteal reaction. Bone scans usually are mildly positive. In contrast to nonossifying fibroma, this lesion is considered a true neoplasm. Because of its tendency for local recurrence, extended curettage or wide resection is recommended.

Fibrous Dysplasia

The radiographic appearance is characteristic, with the lucent area having a granular, ground-glass appearance with a well-defined sclerotic rim (Fig. 25-13). Occasionally, biopsy is necessary to establish the diagnosis. The histopathological appearance is that of irregular woven bone spicules with a fibrous stroma. Small areas of cartilaginous metaplasia and cystic changes may be present (Fig. 25-14). Surgical treatment is indicated when significant deformity or pathological fracture occurs or when significant pain exists. Actual and impending pathological fractures are best treated with intramedullary fixation when possible. Deformities are corrected by osteotomy with internal fixation. Because recurrence rates are high after curettage and bone grafting, cortical bone grafts are preferred over cancellous grafts (or bone graft substitutes) because of their slower resorption. Studies suggest that treatment with bisphosphonates probably is beneficial for patients with extensive disease.