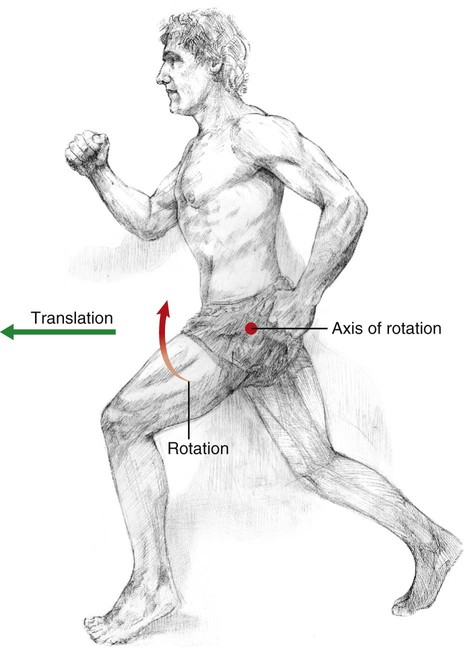

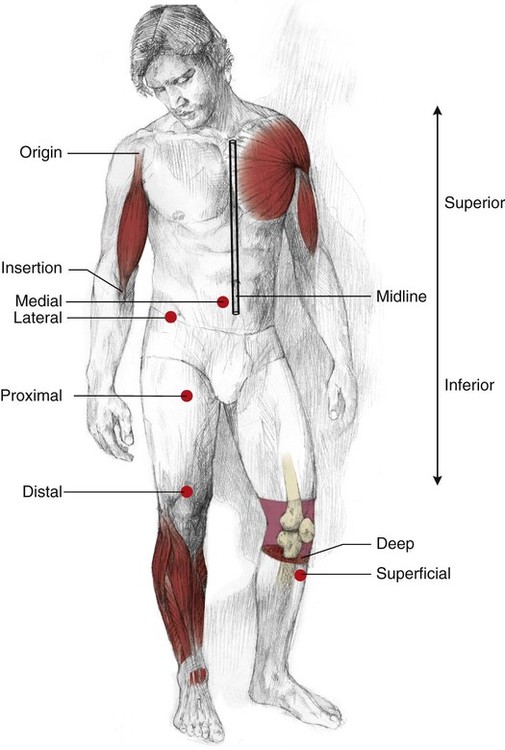

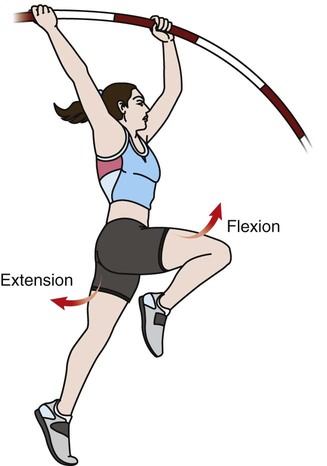

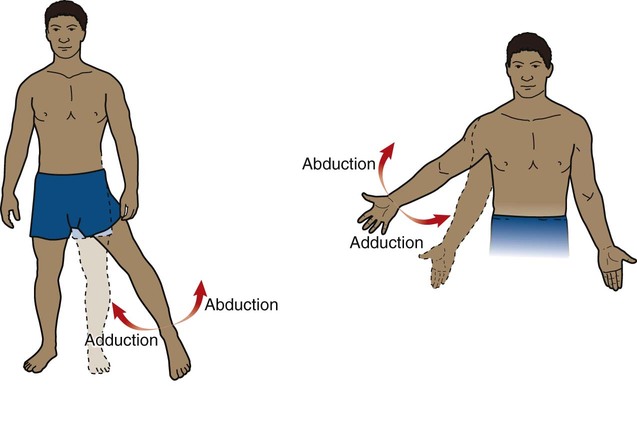

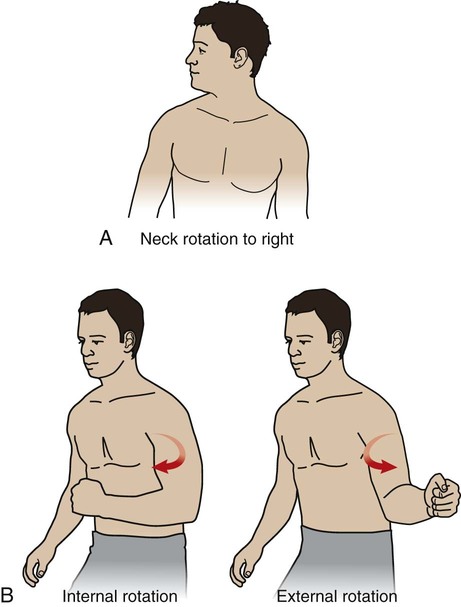

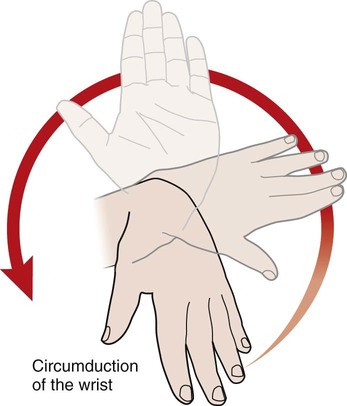

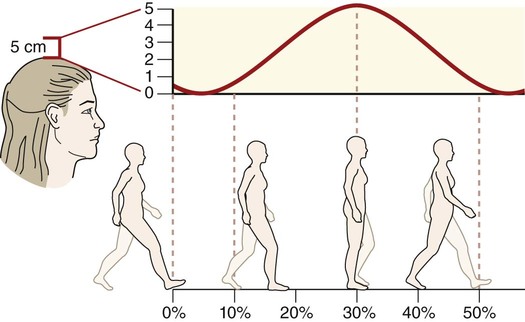

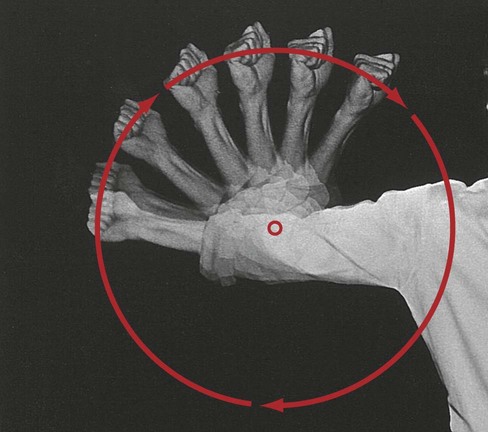

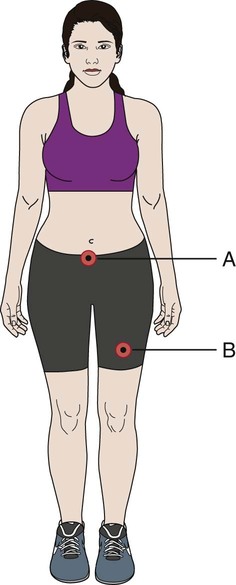

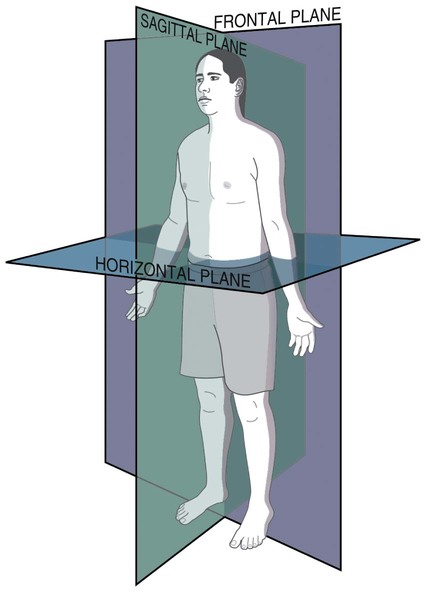

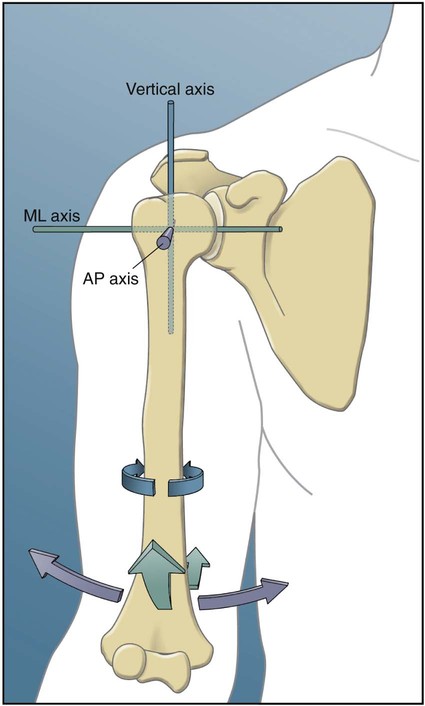

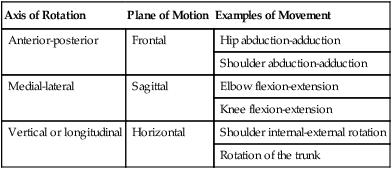

• Define commonly used anatomic and kinesiologic terminology. • Describe the common movements of the body. • Differentiate between osteokinematic and arthrokinematic movement. • Describe the arthrokinematic principles of movement. • Analyze the planes of motion and axes of rotation for common motions. • Describe how force, torque, and levers affect biomechanical movement. • Describe the three biomechanical lever systems, and explain their advantages and disadvantages. • Analyze how muscular lines of pull produce specific biomechanical motions. • Explain how muscular force vectors are used to describe movement. Translation occurs when all parts of a “body” move in the same direction as every other part. This can occur in a straight line (rectilinear motion), for example, sliding a book across a table, or in a curved line (curvilinear motion), such as the arc of a ball being tossed to a friend. Figure 1-1 illustrates the curvilinear motion that occurs during walking, reflecting the normal up-and-down translation of the head as the entire body moves forward. Rotation describes the arc of movement of a “body” about an axis of rotation. The axis of rotation is the “pivot point” about which the rotation of the body occurs. Figure 1-2 illustrates rotation of the forearm around the axis of rotation of the elbow. Movement of the entire human body is generally described as a translation of the body’s center of mass, or center of gravity (Figure 1-3). An activity such as walking results from forward translation of the body’s center of mass, thus the entire body. It is interesting to note, however, that movement or translation of the entire body is powered by muscles that rotate the limbs. This concept is illustrated in Figure 1-4, which shows an individual running (anterior translation of the center of mass) as a result of muscles rotating the legs around the axis of rotation of each hip. It is important to note that the functional movement of nearly all joints in the body occurs through rotation. The study of kinesiology requires the use of specific terminology to describe movement, position, and location of anatomic features. Many of these terms are illustrated in Figure 1-5. • Anterior: Toward the front of the body • Posterior: Toward the back of the body • Midline: An imaginary line that courses vertically through the center of the body • Medial: Toward the midline of the body • Lateral: Away from the midline of the body • Superior: Above, or toward the head • Inferior: Below, or toward the feet • Proximal: Closer to, or toward the torso • Caudal: Toward the feet (or “tail”) • Superficial: Toward the surface (skin) of the body • Deep: Toward the inside (core) of the body • Origin: The proximal attachment of a muscle or ligament • Insertion: The distal attachment of a muscle or ligament • Prone: Describes the position of an individual lying face down • Supine: Describes the position of an individual lying face up Osteokinematics describes the motion of bones relative to the three cardinal planes of the body: sagittal, frontal, and horizontal (Figure 1-6) (Box 1-1). • Sagittal plane: Divides the body into left and right halves. Typically, flexion and extension movements occur in the sagittal plane. • Frontal plane: Divides the body into front and back sections. Nearly all abduction and adduction motions occur in the frontal plane. • Horizontal (transverse) plane: Divides the body into upper and lower sections. Nearly all rotational movements such as internal and external rotation of the shoulder or hip and rotation of the trunk occur in the horizontal plane. The axis of rotation of a joint may be considered the pivot point about which joint motion occurs. Consequently, the axis of rotation is always perpendicular to the plane of motion. Traditionally, movements of the body are described as occurring about three separate axes of rotation: anterior-posterior, medial-lateral, and vertical—sometimes referred to as the longitudinal axis (Figure 1-7). The vertical (longitudinal) axis of rotation is oriented vertically when in the anatomic position. However, if motion occurs out of the anatomic position, it is often described as occurring about the longitudinal axis; this axis courses through the shaft of the bone. Motion about the vertical or longitudinal axis of rotation occurs in the horizontal (or transverse) plane. Typically, these are called rotational movements and are seen in rotation of the trunk when twisting side-to-side or in internal and external rotation of the shoulder. A summary of these axes can be found in Table 1-1. Axes of Rotation and Associated Movements Degrees of freedom refers to the number of planes of motion allowed at a joint. A joint can have 1, 2, or 3 degrees of angular freedom, corresponding to the three cardinal planes (see the earlier section on terminology). As depicted in Figure 1-7, for example, the shoulder has 3 degrees of freedom, meaning the shoulder can move freely in all three planes. The wrist, on the other hand, allows motion in two planes, so it is considered to have 2 degrees of freedom. Joints such as the elbow (humeroulnar joint) allow motion in only one plane and therefore are considered to have just 1 degree of freedom. The motions of flexion and extension occur in the sagittal plane about a medial-lateral axis of rotation (Figure 1-8). Generally, flexion describes the motion of one bone as it approaches the flexor surface of the other bone. Extension is considered a movement opposite that of flexion; it is an approximation of the extensor surfaces of two bones. Rotation describes the movement of a bony segment (or segments) as it spins about its longitudinal axis of rotation. For example, turning the head or turning the trunk side-to-side are considered rotational movements (Figure 1-10, A). Motions of the extremities can be further classified into internal and external rotation. Internal rotation describes the motion of a bony segment that results in the anterior surface of the bone rotating toward the midline. External rotation involves rotation of the anterior surface of a bone rotating away from the midline (Figure 1-10, B). Circumduction describes a circular motion through two planes; therefore joints must have at least 2 degrees of freedom if they are to circumduct. A general rule is that if a joint allows a circle to be “drawn in the air,” the joint can circumduct (Figure 1-11).

Basic Principles of Kinesiology

Kinematics

Terminology

Osteokinematics

Planes of Motion

Axis of Rotation

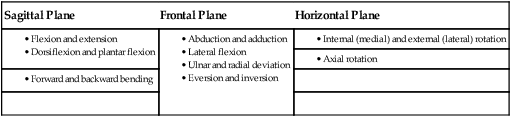

![]() Table 1-1

Table 1-1

Axis of Rotation

Plane of Motion

Examples of Movement

Anterior-posterior

Frontal

Hip abduction-adduction

Shoulder abduction-adduction

Medial-lateral

Sagittal

Elbow flexion-extension

Knee flexion-extension

Vertical or longitudinal

Horizontal

Shoulder internal-external rotation

Rotation of the trunk

Degrees of Freedom

Fundamental Movements

Flexion and Extension

Rotation

Circumduction

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree