CHAPTER 21 Back Pain in Children and Adolescents

The prevalence of back pain in children and adolescents is increasing. Although it is assumed that pediatric back pain is rare, more recent studies have shown that more than 50% of children note episodes of back pain by 15 years of age.1–4 A survey of teenagers revealed that 39% complained of low back pain, but few presented for medical evaluation.5 Although the number of children and teens complaining of pain is increasing, children and adolescents who have a distinct diagnosis are decreasing in number. A study by Hensinger6 in 1985 found a specific diagnosis in 84% of children presenting for treatment of back pain. In a study 10 years later, a cause for back pain was identified in only 22% of 217 children evaluated with single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT).7 The task of the evaluating surgeon is to identify which children are most likely to have an underlying musculoskeletal condition and require a comprehensive evaluation to identify the etiology of their pain.

History

The initial step in distinguishing which children require symptomatic treatment from children who warrant a complete radiographic evaluation is obtaining a detailed history. The characteristics of the pain are most helpful. Acute pain after trauma is seen with fractures, disc herniations, and apophyseal ring separations. Insidious pain without a clear-cut antecedent event is characteristic of developmental conditions, such as Scheuermann kyphosis, and benign neoplasms. Recurrent pain associated with athletics and relieved by rest leads to suspicion of overuse injuries such as spondylolysis. Unremitting pain, especially if it is worse at night or wakes the child from sleep, is most worrisome because it is seen in malignancies and infection.7,8

The patient’s age is very helpful in directing the evaluation of back pain. Back pain in children younger than 4 years is usually due to either infection or malignancy. A history of fever, limp, and malaise should be sought, and an immediate diagnostic evaluation should be performed. Children in the 1st decade of life commonly present with discitis and osteomyelitis, and malignant neoplasms, but they also may present with benign conditions such as eosinophilic granuloma.8 Patients older than 10 years are most likely to have back pain secondary to trauma or overuse, resulting in spondylolysis, disc herniations, or apophyseal fractures.9 Scheuermann kyphosis manifests in adolescence. Teens also rarely present with malignancies, so the physician should always remain cautious while weighing the relative frequency of conditions based on age.

A family history should be taken regarding back pain. Adolescents with ill-defined pain, no constitutional symptoms, no history of excessive athletic activity, no anatomically consistent neurologic complaints, and a positive family history often do not have a musculoskeletal etiology for their pain.2,8 Psychosomatic pain does occur in this age group, but remains a diagnosis of exclusion.

A complete review of systems should be obtained. Back pain associated with menses is rarely orthopaedic in nature. Flank pain may be renal in origin. A more recent study showed that 5% of children presenting to an emergency department for evaluation of back pain had urinary tract infections.10

Diagnostic Studies

With the information obtained from the history and physical examination, a focused approach to diagnostic studies can be taken (Table 21–1). If the patient is 10 years of age or younger, if the duration of pain is 2 months or longer, if there is night pain, or if there are constitutional symptoms, standard radiographs of the spine should be obtained immediately. If the patient is older, the pain is of short duration, and the physical examination is completely normal, the patient may be observed for a short time. Most patients fall between these two groups, and the extent of the radiographic evaluation should be decided on an individual basis.

TABLE 21–1 Use of Diagnostic Tests

| X-ray | History of significant trauma; night pain, fever, or inability to walk; age ≤8 yr; duration of pain >2 mo |

| Bone scan | Negative plain x-rays with normal neurologic examination; persistent pain; history of athletic overuse |

| Computed tomography | Positive plain x-ray or bone scan |

| Magnetic resonance imaging | Abnormal neurologic examination; painful scoliosis in patient <8 yr old; painful left thoracic scoliosis |

| Laboratory tests | Night pain; fever; age <8 yr; constant pain |

Radiographs

Plain radiographs are the best screening examination for a child with back pain.7,11 Anteroposterior and lateral views of the spine should be obtained without pelvic shielding because the shield hides the sacrum, the sacroiliac joints, and the pelvis. The physician should carefully examine the films for alignment, disc space narrowing, endplate irregularities, and lytic or blastic lesions. Each pedicle should be identified on the anteroposterior view. If a question of a lesion arises, a focused coned-down view taken with the patient supine provides better bony detail.

The identification of scoliosis on screening films of a child with back pain should not lead to the conclusion that the curve is the cause of the pain. Although 33% of adolescents with the diagnosis of scoliosis complain of some back pain, it is usually located over the rib prominence and is rarely a presenting complaint.11 The apex of the curve should be carefully inspected for bony lesions in a child with painful scoliosis.

Bone Scan

SPECT combines the physiology of a bone scan with the ability to localize lesions precisely within the vertebra similar to a computed tomography (CT) scan. Increased uptake can be seen in the posterior elements in stress fractures, so SPECT is particularly helpful in diagnosing spondylolysis.12–15 A study of 100 patients 2 to 18 years old presenting with low back pain found that a negative SPECT scan was most helpful in ruling out an organic cause for back pain of less than 6 weeks’ duration.16

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI is used to image the neural axis in all children who have an abnormal neurologic examination. MRI can identify spinal neoplasms, cord abnormalities such as syringomyelia and tethers, discitis, and herniated discs. Auerbach and colleagues16 recommended MRI as the best imaging modality for patients with low back pain of greater than 6 weeks’ duration.

Differential Diagnosis

Table 21–2 summarizes differential diagnoses based on the child’s age.

TABLE 21–2 Likely Diagnoses Based on Age

| Age <5 yr | Tumor, discitis |

| Age 5-10 yr | Langerhans cell histiocytosis, discitis, tumor or leukemia |

| Age 10-18 yr | Scheuermann kyphosis, herniated disc or apophysis, spondylolysis, osteoid osteoma, tumor or leukemia |

Disc Herniation

Intervertebral disc herniation occasionally occurs in older children and teens. The onset of symptoms is usually related to acute or repetitive trauma.17 Back pain with radiation into the legs is a complaint in 82% of affected patients.18 Pain is exacerbated by activity and relieved by rest. As in adults, pain is worsened by sneezing, coughing, or straining.

Physical examination reveals decreased spinal flexibility, with inability to touch the toes. On bending toward the floor, the patient often lists to one side. The straight-leg raise test (Lasègue sign) is positive in 85% of children with herniated discs; objective neurologic findings, such as absent reflexes, motor weakness, and decreased sensation, are less common in children than in adults.19

Radiographs are generally normal, although if the child is sufficiently symptomatic, films may show an olisthetic scoliosis or trunk lean. There is an increased incidence of concomitant spinal abnormalities in patients with herniated discs. In particular, congenital spinal stenosis is frequently seen. Other findings include transitional vertebrae or spondylolisthesis.20

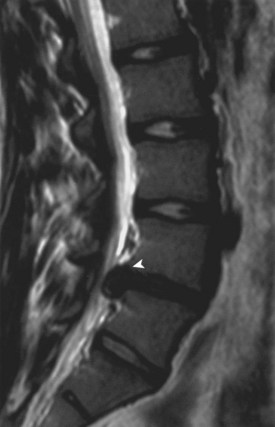

Disc herniation is seen best on MRI (Fig. 21–1). The involved disc is readily appreciated, and other processes that might produce sciatica, such as epidural abscess and spinal cord tumor, can be ruled out.8 Herniation of the disc can be differentiated from an avulsed vertebral apophysis on either MRI or CT scan. Correlation of MRI findings with the history and clinical examination is necessary because mild disc bulging can exist as a normal variant.

Treatment is initially conservative, consisting of anti-inflammatory medication and bed rest. Prolonged nonoperative management may lead to persistent pain, however, so if the patient does not respond to symptomatic treatment, disc excision should be performed.19 Short-term results are very encouraging, with 95% good and excellent results and nearly universal resolution of back and leg pain.19 Although long-term follow-up shows deterioration in results, with 24% reoperation after 30 years,21 outcome studies show that patients treated by discectomy as adolescents function better than adults after similar surgery.22 Surgical technique for adult and pediatric patients is similar. Some early reports indicate pediatric patients can safely undergo endoscopic percutaneous discectomy.23

Apophyseal Ring Fracture (Slipped Vertebral Apophysis)

The apophyseal ring fracture, also known as a slipped vertebral apophysis, occurs in adolescents and young adults. The etiology is either acute trauma resulting in rapid flexion and axial compression or cumulative microtrauma. The fracture typically develops at the junction of the posteroinferior vertebral body and the cartilaginous ring apophysis, with posterior displacement of the fragment into the spinal canal.24 CT scan can show the size and location of the bony fragment, with large central fragments being most common and most likely to result in significant pain if left untreated.25

The diagnosis is made radiographically. High-quality lateral radiographs may show an arc-shaped rim of cartilage, cartilage with attached underlying bone, or a small triangular bony fragment lying posterior to the vertebral body. The fragment is best visualized on CT scan.24 The levels most frequently injured are L4 or S1. Treatment is surgical removal of the avulsed fragment.

Developmental Disorders

Spondylolysis and Spondylolisthesis

Spondylolysis refers to a stress fracture of the pars interarticularis, occurring predominantly in the lower lumbar spine. The most frequent level is L5, followed by L4. It is extremely rare to have more than one vertebral level involved. Spondylolysis is bilateral in 80% of cases and unilateral in 20%. More recent studies show that 50% of young athletes presenting for evaluation of back pain have injuries to the pars interarticularis.26 The mechanism of injury is repetitive microtrauma in hyperextension, overloading the pars interarticularis, over time leading to stress fracture. Sports linked to a high incidence of spondylolysis are gymnastics, diving, ballet, and football. Gymnasts and football linemen have a fourfold increase in incidence of spondylolysis compared with the general pediatric population.27

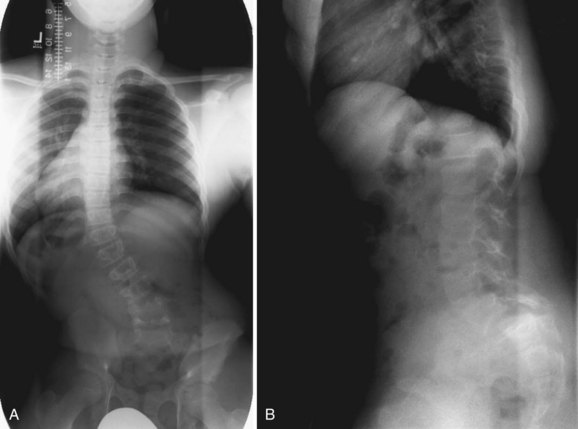

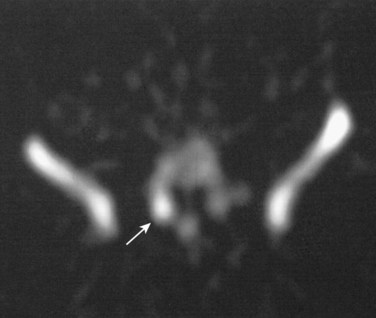

Lateral radiographs may show lysis across the pars interarticularis, and oblique radiographs can be helpful in less obvious cases (Fig. 21–2). The appearance of a collar on the “Scottie dog” suggests stress fracture. Often, plain radiographs are nondiagnostic. In these cases, scintigraphy can reveal increased tracer uptake at the involved level. The use of SPECT is particularly helpful in localizing increased uptake in the pars interarticularis (Fig. 21–3).13,14,28 A specific scintigraphic pattern, seen as a triangle of increased signal with increased uptake in the pedicles, has been described.29 Positive bone scans and SPECT imaging are generally seen in the prefracture state and in relatively acute injuries.30 The bone scan may not be “hot” in chronic spondylolysis.14

FIGURE 21–2 Lateral radiograph of lumbar spine shows spondylolysis of L5 in a 16-year-old volleyball player.

FIGURE 21–3 Increased uptake in pars interarticularis of an adolescent ballerina with spondylolysis.

MRI has also been used to diagnose spondylolysis, but false-positive scans can occur.31 Better bony definition of the fracture is obtained using CT scans. Additionally, CT is superior to MRI in the assessment of incomplete fractures and in establishing healing in patients with spondylolysis.32 The pars is imaged by using a reverse gantry angle and obtaining thin slices on the CT scan.33

Treatment of spondylolysis is initially nonoperative and primarily involves modifying the patient’s level of athletic activity.34 Cessation of sport until the resolution of symptoms is combined with a concomitant exercise program to stretch the hamstrings and strengthen the paraspinal and abdominal musculature. Resumption of activities is gradual. The patient’s technique or training should be modified to minimize recurrent fractures. Use of a antilordotic lumbar orthosis increases the success of nonoperative treatment, particularly in patients with acute injuries and “hot” bone scans.35,36 A more recent study found resolution of symptoms after bracing correlated with initial increased activity on SPECT scans and with decreased uptake on follow-up scans, whereas SPECT scans for patients whose pain did not improve showed no significant decrease in activity after bracing.37

The overall success rate of nonoperative treatment ranges from 73% to 100%.36 A multicenter study of 436 children and adolescents with CT-proven spondylolysis found 95% excellent results and 100% return to sport without surgery after 3 months of cessation of activity with use of a thoracolumbar orthosis.38 Patients who have normal radiographs but are found to have a stress reaction without fracture on further imaging are highly likely to improve (and not progress to radiographic fracture) with conservative treatment.39,40 Surgery is typically reserved for the few patients whose symptoms are refractory to 6 months of conservative measures and whose pain recurs with activity after initial nonoperative success.41

Spondylolisthesis is a related condition in which anterior slippage of a vertebral body occurs on the more distal vertebra. Most often, it is due to bilateral spondylolysis, with the portion of the vertebra anterior to the pars fracture slipping anteriorly. Dysplastic spondylolisthesis occurs in teens who have an elongated but intact pars interarticularis, which allows for the anterior translation without pars fracture.42

Patients with spondylolisthesis often present with complaints of low back pain. The pain may radiate into the legs. Physical findings mimic findings of spondylolysis, with the addition of a possible palpable step-off at the area of listhesis. In severe spondylolisthesis, the buttocks may appear “heart-shaped.” If there is significant hamstring tightness, gait alterations are seen: The teen appears to be shuffling with posterior pelvic tilt. Patients may have a painful, or olisthetic, scoliosis (Fig. 21–4).

Treatment is initially conservative in mild spondylolisthesis and surgical as the magnitude of the slip increases. Surgical treatment of high-grade spondylolisthesis is recommended, but preferred techniques vary among surgeons, and reduction remains controversial.43 The surgical treatment of spondylolisthesis and spondylolysis is discussed in further detail in Chapter 27.

Scheuermann Kyphosis

The diagnosis is made radiographically (Fig. 21–5). Criteria for the diagnosis of Scheuermann disease have been outlined by Sorenson as (1) three contiguous vertebral bodies with greater than 5 degrees of anterior wedging; (2) abnormal disc narrowing; (3) endplate irregularities; and (4) Schmorl nodes, defined as disc herniations into the vertebral bodies.

Most patients with Scheuermann disease can be managed nonoperatively.44 Physical therapy exercises and nonsteroidal medication can be helpful in relieving symptoms. The role of bracing is controversial. Patients with significant remaining spinal growth may benefit from orthotic treatment; it has been proposed that correction of deformity may be achieved in compliant patients.45 The Milwaukee brace is the orthosis of choice for the treatment of Scheuermann disease.46 Surgical correction of deformity and fusion is reserved for patients with severe kyphosis measuring greater than 75 degrees, patients whose symptoms are refractory to conservative measures, and patients who have significant cosmetic concerns.47 The management of Scheuermann kyphosis is discussed in Chapter 26.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree