Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation

Brian T. Feeley

Christina R. Allen

Hubert T. Kim

INTRODUCTION

Autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) was first described in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1994 (1). At that time, ACI was a truly pioneering application of tissue engineering to treat full-thickness cartilage defects. In this technique, chondrocytes are isolated from the patients’ own articular cartilage, expanded ex vivo, and reimplanted into the defect under a periosteal patch. The primary advantages of ACI are the ability to address relatively large defects and the development of more hyaline-like cartilage within the repair site (2). Theoretically, the presence of more hyaline-like cartilage will enhance the long-term durability and performance of the repair tissue.

Indications

The indications for ACI are similar to those of other cartilage procedures. The appropriate patient has a symptomatic grade III to IV lesion on the weight-bearing portion of the femoral condyle(s) or trochlea, between the ages of 15 and 55 years (Fig. 42.1). The typical size of the lesion is between 2 and 12 cm2. Larger lesions and/or multiple lesions are also amenable to ACI treatment. Many patients would have had one or more prior cartilage procedure (i.e., debridement or microfracture). It is generally our preference to avoid performing microfracture in patients who are likely to undergo ACI. Although bony involvement is not a strict contraindication, bone loss of more than 6 mm in depth generally precludes the use of traditional ACI. However, significant bone involvement can be addressed by combining ACI with staged or concurrent bone grafting. Patients with grade III or grade IV reciprocal “kissing” lesions on the femur or tibia are not good candidates for ACI. Patients who are unable to be compliant with the postoperative restrictions and rehabilitation program should not undergo this procedure. Malalignment or instability of the affected limb that would overload the repair tissue should be corrected either before or at the time of ACI. It is our usual practice to perform any necessary corrective surgeries first and allow for recovery prior to any ACI procedures; however, other surgeons regularly perform ACI in conjunction with concurrent osteotomy and/or ligament reconstruction with good results.

Surgical Technique

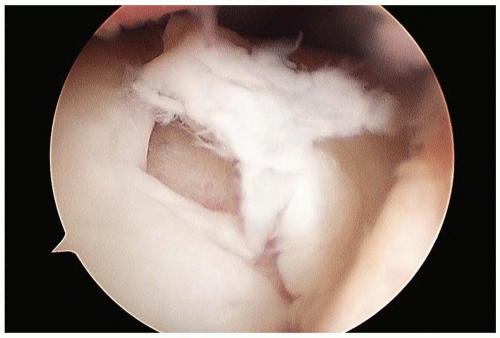

The technique for standard ACI has remained essentially unchanged since its original description (Figs. 42.2, 42.3, 42.4 and 42.5). The initial phase of ACI, harvesting of the patient’s articular cartilage, typically is performed as part of a standard knee arthroscopy. During the arthroscopy, areas of grade III to IV cartilage change are identified, and the size of the lesion is determined. Care is taken to identify any reciprocal grade III or IV “kissing” lesions, as this would be a contraindication to proceeding with ACI. Cartilage biopsies are usually obtained from the superomedial or superolateral aspect of the femoral condyles along the peripheral margin of articular cartilage. Alternatively, cartilage biopsies can be taken from the intercondylar notch. There are no data to suggest that any of these sites is clearly superior to the others. The cartilage biopsy is obtained using a gouge or ringed curette to remove approximately 200 to 300 mg (two “Tic Tacs”) of tissue. A sharp gouge is frequently easier and more efficient to use than a curette. Inclusion of a small amount of bone with the cartilage specimen is common and not a problem, as subsequent processing prior to in vitro expansion will remove the contaminating

bone component. While it may be tempting in some cases to harvest mildly degenerative cartilage, we believe this is should be avoided. The harvested tissue is placed into a sterile transport container that is shipped to the cell processing facility. In the United States, almost all cartilage tissue processing for ACI is performed by Genzyme Corporation (Cambridge, Massachusetts). Chondrocytes are released from the cartilage matrix by enzymatic digestion and are then expanded under standard tissue culture conditions. The details of this process are considered proprietary and may vary slightly from one facility to another. The end product is a cell suspension of partially dedifferentiated chondrocytes. Typically, one vial of cells containing approximately 12 million cells is sufficient to treat a defect up to 7 cm2 in size. Larger lesions may require more than one vial of cells, and this must be taken into account when sizing the defect(s), harvesting cartilage, and ordering cells for implantation.

bone component. While it may be tempting in some cases to harvest mildly degenerative cartilage, we believe this is should be avoided. The harvested tissue is placed into a sterile transport container that is shipped to the cell processing facility. In the United States, almost all cartilage tissue processing for ACI is performed by Genzyme Corporation (Cambridge, Massachusetts). Chondrocytes are released from the cartilage matrix by enzymatic digestion and are then expanded under standard tissue culture conditions. The details of this process are considered proprietary and may vary slightly from one facility to another. The end product is a cell suspension of partially dedifferentiated chondrocytes. Typically, one vial of cells containing approximately 12 million cells is sufficient to treat a defect up to 7 cm2 in size. Larger lesions may require more than one vial of cells, and this must be taken into account when sizing the defect(s), harvesting cartilage, and ordering cells for implantation.

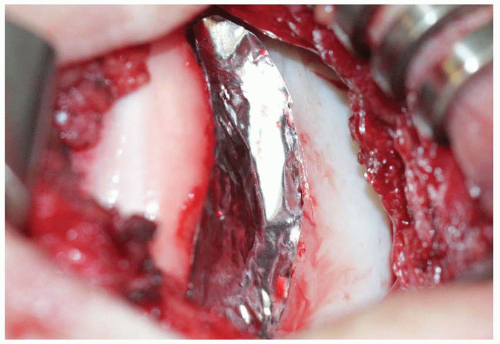

The second procedure for implantation of the expanded chondrocyte cells is performed a minimum of 4 weeks following the index procedure to allow for in vitro expansion of the harvested chondrocytes. The procedure can be performed under either general or regional anesthesia. The patient is positioned supine on a standard operating table. It is helpful to tape a sand bag or 3-L saline bag to the table at the midcalf level so that

the knee can be held flexed to approximately 90 degrees. An Alvarado positioner can be used instead, and it has the added benefit of being able to fine-tune the knee position for optimal exposure. A lateral post is also useful to keep the leg vertically positioned. The leg is prepped distal to a nonsterile tourniquet, which is not typically inflated. For most cases, we prefer a midline skin incision, which can most easily be incorporated into any future surgical procedures on the knee. Alternatively, a parapatellar skin incision can be used and is equally effective. The arthrotomy is performed based on the location of the lesion. For trochlear lesions, we favor a medial parapatellar arthrotomy with a “midvastus” extension as necessary. Any dissection distally along the tibial plateau should be performed carefully in order not to damage the anterior horn of the medial or lateral meniscus.

the knee can be held flexed to approximately 90 degrees. An Alvarado positioner can be used instead, and it has the added benefit of being able to fine-tune the knee position for optimal exposure. A lateral post is also useful to keep the leg vertically positioned. The leg is prepped distal to a nonsterile tourniquet, which is not typically inflated. For most cases, we prefer a midline skin incision, which can most easily be incorporated into any future surgical procedures on the knee. Alternatively, a parapatellar skin incision can be used and is equally effective. The arthrotomy is performed based on the location of the lesion. For trochlear lesions, we favor a medial parapatellar arthrotomy with a “midvastus” extension as necessary. Any dissection distally along the tibial plateau should be performed carefully in order not to damage the anterior horn of the medial or lateral meniscus.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|