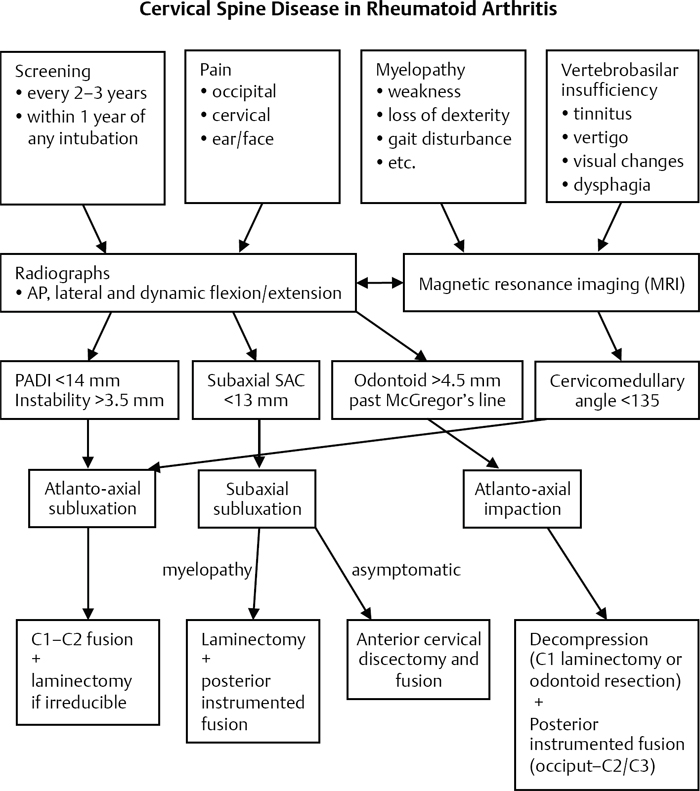

50 Tuberculosis (TB) and fungal infections are the most common atypical spine infections. Since the advent of antitubercular drugs and improved public health measures, spinal tuberculosis has become rare in developed countries, although it is still a significant cause of disease in developing countries. About 5% of those with TB will develop spinal involvement due to hematogenous spread from the primary site in the lungs or the genitourinary system. The primary symptoms of TB may go unrecognized until the development of a TB spondylitis. Various factors have been suggested to predispose a patient to spinal atypical infections, including an immunocompromised state, trauma, or other infections. TB most commonly affects the thoracic and lumbar spine and rarely involves the cervical spine or sacrum. Involvement of two vertebral levels is seen in ~ 70% of cases, with three or more levels involved in 20%. The most common fungal organisms to infect the spine are Aspergillus, Candida, Cryptococcus, and actinomycetes. As with TB, immunosuppression plays a major role in predisposing to fungal spondylitis. In recent years, the incidence of fungal spinal infections has increased as a result of a growing incidence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections, organ transplantation, and immunosuppressed patients with concomitant diseases requiring prolonged corticosteroids, antirheumatic drugs, hemodialysis, or chemotherapy agents. Atypical spinal infections generally begin in the anterior spine and soft tissues and progress posteriorly. There are two common patterns of spinal tuberculosis. The first is the classical pattern (spondylodiskitis), which is characterized by destruction of two or more adjacent vertebrae with spread anteriorly across the disk space. There is relative sparing of the disk space, in contrast to classic pyogenic spinal infections. The second pattern is tuberculous spondylitis, which generally shows large abscesses in the perivertebral soft tissue, which may extend along the anterior vascular structures along with bony destruction and collapse (into kyphosis) of the vertebral column. In some cases the abscess may extend into the spinal canal, producing a neurological deficit. These two types should be viewed as a continuum of disease severity. Clinical presentation of atypical spinal infection is often nonspecific. Often the symptoms are generally insidious, with a slow, progressive course of generalized weakness, malaise, night sweats, fevers, and weight loss. Often there are complaints of slowly increasing local pain, muscle spasm, and occasionally radicular symptoms. Severe pain or obvious deformity is generally a late finding that may be related to bone collapse and/or impending paralysis. A complete physical and neurologic examination should be conducted. In most cases, the physical examination is nonspecific unless a patient has neurologic involvement. Laboratory studies are consistent with a chronic disease, including mild anemia, hypoproteinemia, and mild elevations of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP). Plain radiographs may demonstrate destructive involvement of the vertebral column or deformity. Computed tomography (CT) scanning is helpful to define the degree of bony destruction. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the imaging study of choice in most cases and will show early infections (before significant destruction is seen on plain films) and also soft-tissue extension and/or neurologic compression. Biopsy for culture and histologic analysis is crucial to define the nature of the infection. Biospy specimens should be sent for aerobic, anaerobic, acid-fast, and fungal cultures as well as gram stain and histology. Atypical organisms tend to be slow growing, so the cultures should be maintained for an extended period (3 months) before assuming that no growth is present. Nonsurgical therapy is appropriate for cases without significant deformity, instability, or neurologic involvement. Nonsurgical therapy consists of antimicrobial therapy and bracing. Prolonged antimicrobial therapy is generally required for atypical spinal infections. Surgical débridement, spinal reconstruction, and/or spinal canal decompression are indicated for patients who fail nonsurgical management or those with significant spinal deformity, instability, or neurologic compromise. In these cases, radical débridement of the infection is performed with reconstruction of the involved area of the spine. Stable fixation is paramount to the success of treatment. In addition, prolonged antimicrobial therapy is utilized to control the infection and reduce the risk of recurrence. With proper treatment, the prognosis for patients with atypical spinal infections is fair. Cure rates of 85% have been quoted in the literature, although patients with substantial medical comorbidities and/or immunosupression have a much higher rate of mortality compared with those with relatively normal immune function. Hirakawa A, Miyamoto K, Ohno Y, et al. Two-stage (posterior and anterior) surgical treatment of spinal osteomyelitis due to atypical mycobacteria and associated thoracolumbar kyphoscoliosis in a nonimmunocompromised patient. Spine 2008;33(7):E221–E224 PubMed This reviews the surgical treatment approach to an atypical spinal infection. Jain AK. Tuberculosis of the spine: a fresh look at an old disease. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2010; 92(7):905–913 PubMed This is an excellent review of spinal tuberculosis and reviews diagnosis and treatment approaches in the modern era. Sobottke R, Zarghooni K, Seifert H, et al. Spondylodiscitis caused by Mycobacterium xenopi. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2008;128(10):1047–1053 PubMed This article reviews the treatment of atypical spinal infections caused by nontuberculous organisms. Any evidence of spinal cord impingement or signal change in the cord should prompt further surgical evaluation. PADI, posterior atlantodens line between the hard palate and opisthion; SAC, space available for the spinal cord

Atypical Infections of the Spine: Tuberculosis and Fungal

![]() Classification

Classification

![]() Workup

Workup

History

Physical Examination

Special Diagnostic Tests

Laboratory Studies

Imaging Studies

Biopsy and Culture

![]() Treatment

Treatment

Nonsurgical Treatment

Surgical Treatment

![]() Outcome

Outcome

Suggested Readings

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree