CHAPTER 33 Arthritic Disorders

Ankylosing Spondylitis

Epidemiology

AS affects 1% to 2% of whites, which is equal to the prevalence for RA. A strikingly high association between HLA-B27 and AS has been shown. HLA-B27 is present in more than 90% of white patients with AS compared with a frequency of 7% to 8% in a normal white population.1 In North American whites, with a prevalence of HLA-B27 of 7%, the frequency of AS is 0.2%.2 A positive family history of AS or related spondyloarthropathy increases the risk to 30% among HLA-B27–positive first-degree relatives compared with HLA-B27–positive control subjects (1% to 4%).3

The male-to-female ratio is reported in the range of 3:1. Women tend to be less symptomatic, however, and develop less severe disease. Women may also present more often with cervical spine disease with minimal lumbar spine symptoms. The overall pattern of illness may be similar in men and women.4

Pathogenesis

Enthesitis is the hallmark that distinguishes the spondyloarthropathies from other forms of arthritis.5 An enthesis is a dynamic structure undergoing constant modification in response to applied stress. This area is a target for inflammation. Although entheses are primarily affected in the spondyloarthropathies, inflammation of these structures is insufficient to explain the alterations that occur in joints (sacroiliac). Synovitis plays an important role. Synovitis may be a secondary event, however, after initiation with an enthesitis.6

Clinical History

The classic AS patient is a man 15 to 40 years old with intermittent dull low back pain. The associated stiffness is slowly progressive, measured in months to years. AS rarely occurs in individuals older than 50 years. Patients with spondyloarthropathy initiated after age 50 are more likely to have a non-AS spinal inflammatory disorder, such as psoriatic spondylitis.7 Back pain, which occurs throughout the disease in 90% to 95% of patients, is greatest in the morning and is increased by periods of inactivity. Patients may have difficulty sleeping because of pain and stiffness; they may awaken at night and find it necessary to leave bed and move about for a few minutes before returning to sleep. Fatigue can be a major symptom and correlates with level of disease activity, functional ability, global well-being, and mental health status.8

Back pain improves with exercise. The mode of onset is variable, with most patients developing pain in the lumbosacral region. Peripheral joints (hips, knees, and shoulders) are initially involved in a few patients, and occasionally acute iridocyclitis (eye inflammation) or heel pain may be the first manifestation of disease. Occasionally, individuals older than 50 years may present with mild symptoms despite extensive spinal involvement.9 Conversely, back pain may be severe, with radiation into the lower extremities, mimicking acute lumbar disc herniation. Patients have symptoms related to the piriformis syndrome. The belly of the piriformis muscle crosses over the sciatic nerve. Inflammation in the sacroiliac joint, where the muscle attaches, results in muscle spasm and nerve compression. There are no abnormal, persistent neurologic signs associated with the sciatic pain. The symptoms are reversible with medical therapy that relieves joint inflammation. This symptom complex of radicular pain is referred to as pseudosciatica.

Neurologic Complications

Atlantoaxial Subluxation

Neurologic complications of AS are secondary to nerve impingement or trauma to the spinal cord. In a study of 33 patients with AS and neurologic complications, cervical abnormalities were the most common cause of neurologic compromise.10 Atlantoaxial subluxation occurs in the setting of AS but less often than in RA.11 In a study of 103 AS patients, 21% had atlantoaxial subluxations. Vertical subluxation is a rare complication. About one third of patients have progression of subluxations. Five of the 22 patients with subluxation required surgical fusion.12 Rarely, symptoms of atlantoaxial subluxation may be the presenting manifestation of AS.13 Significant instability may occur without symptoms in RA because of generalized ligamentous laxity and erosion of bone. AS patients have symptoms and signs of nerve impingement more frequently in the setting of instability secondary to the immobilized state of the calcified structures surrounding the spine. Spinal cord compression is associated with myelopathic symptoms, including sensory deficits, spasticity, paresis, and incontinence.

Spinal Fracture

The other change is the loss of normal flexibility because of ankylosis of the spinal joints and ligaments. The spine in this ankylosed state is much more brittle and is prone to fracture, even with minimal trauma. The most common location for fracture is the cervical spine, although dorsal and lumbar spine fractures have also been described.14,15 The occurrence of traumatic cervical spine injury is 3.5 times greater in AS patients than in the normal population.16 The frequency of AS as the cause of spinal cord injury is 0.3% to 0.5%.17 The lower cervical spine (C6-7) is the most frequent location for fracture, which is often associated with a fall. Patients who develop fractures may complain of nothing more than localized pain and decreased or increased spinal motion, but severe sensory and motor functional loss corresponding to the location of the lesion may develop. The onset of neurologic dysfunction may be delayed for weeks after initial trauma.

The diagnosis of fracture may be delayed because of the difficulty of detecting fractures in osteoporotic bone with plain radiographs. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of these patients may identify the location of the fracture.15 Neurologic deficits may persist despite surgical intervention in 85.7% of patients.18 A mortality rate of 35% to 50% may be found particularly in AS patients who are elderly, who have complete cord lesions, or who develop pulmonary complications after fracture.19

Laboratory Data

Laboratory results are nonspecific and add little to the diagnosis of AS. Mild anemia is present in 15% of patients. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate is increased in 80% of patients with active disease. Patients with normal sedimentation rates with active arthritis may have elevated levels of C-reactive protein.20 Rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibody are characteristically absent. Histocompatibility testing (for HLA) is positive in 90% of AS patients but is also present in an increased percentage of patients with other spondyloarthropathies (reactive arthritis, psoriatic spondylitis, and spondylitis with inflammatory bowel disease). It is not a diagnostic test for AS. HLA testing may be useful in a young patient with early disease for whom the differential diagnosis may be narrowed by the presence of HLA-B27.

Radiographic Evaluation

Characteristic changes of AS in the sacroiliac joints and lumbosacral spine are helpful in making a diagnosis but may be difficult to determine in the early stages of the disease.21 The areas of the skeleton most frequently affected include the sacroiliac, apophyseal, discovertebral, and costovertebral joints. The disease affects the sacroiliac joints initially and then appears in the upper lumbar and thoracolumbar areas. Subsequently, in ascending order, the lower lumbar, thoracic, and cervical spine are involved. The radiographic progression of disease may be halted at any stage, although sacroiliitis alone is a rare finding except in some women with spondylitis or in men in the early stage of disease.

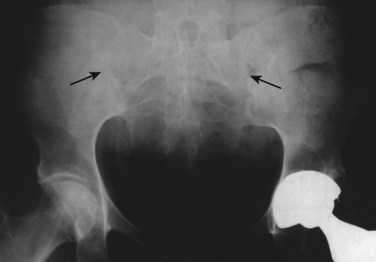

Sacroiliitis is a bilateral, symmetrical process in AS. During the next stage, the articular space becomes “pseudowidened” secondary to joint surface erosions. With continued inflammation, the area of sclerosis widens and is joined by proliferative bony changes that cross the joint space. In the final stages of sacroiliitis, complete ankylosis with total obliteration of the joint space occurs (Fig. 33–1). Ligamentous structures surrounding the sacroiliac joint may also calcify. The radiographic changes associated with sacroiliitis may be graded from 0 (normal) to 5 (complete ankylosis).

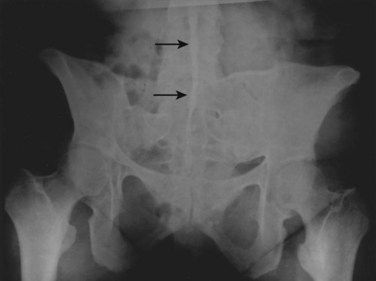

In the lumbar spine, osteitis affecting the anterior corners of vertebral bodies is an early finding. The inflammation associated with osteitis causes loss of the normal concavity of the anterior vertebral surface, resulting in a “squared” body (Fig. 33–2).

While osteopenia of the bony structures appears, calcification of disc and ligamentous structures emerges. Thin, vertically oriented calcifications of the anulus fibrosus and anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments are termed syndesmophytes. Bamboo spine is the term used to describe the spine of a patient with AS with extensive syndesmophytes encasing the axial skeleton (Fig. 33–3).

The apophyseal joints are also affected in the illness. As the disease progresses, fusion of the apophyseal joints occurs. Radiographs of the spine may show the loss of joint space and complete fusion of the joints. Cervical spine ankylosis may be particularly severe (Fig. 33–4). Complete obliteration of articular spaces between the posterior elements of C2-7 results in a column of solid bone. Patients with complete ankylosis of the apophyseal joints and syndesmophytes may develop extensive bony resorption of the anterior surface of the lower cervical vertebrae late in the course of the illness. Bone under the ligaments connecting the spinous processes may also be eroded in the setting of apophyseal joint ankylosis.

FIGURE 33–4 Ankylosing spondylitis. Lateral view of cervical spine of the patient in Figure 33–3. Radiograph shows anterior syndesmophytes (white arrows) and fusion of posterior zygapophyseal joints (black arrow).

MRI with fat saturation or contrast medium–enhanced images are able to detect early inflammatory lesions in the sacroiliac joints and the lumbar spine.22 From a diagnostic and clinical perspective, plain radiographs normally provide adequate information at a reasonable cost. Plain radiographs remain the usual radiographic technique used for the diagnosis of AS. MRI is a good choice for young women with suspected sacroiliitis as a means of decreasing radiographic exposure.

Differential Diagnosis

Two sets of diagnostic criteria exist for AS. The Rome clinical criteria, used in studies of AS, include bilateral sacroiliitis on radiologic examination and low back pain for more than 3 months that is not relieved by rest, pain in the thoracic spine, limited motion in the lumbar spine, and limited chest expansion or iritis. When the Rome criteria proved to lack sensitivity in identifying patients with spondylitis, they were modified at a New York symposium in 1966 (Table 33–1). The modified criteria included a grading system for radiographs of the sacroiliac joints in addition to limited spine motion, chest expansion, and back pain.23 Although these criteria are used mostly for studies of patient populations, they are helpful in the office setting. The European Spondyloarthropathy Study Group developed a preliminary classification system for spondyloarthropathy in general (Table 33–2).24

TABLE 33–1 Diagnostic Criteria for Ankylosing Spondylitis

TABLE 33–2 European Spondyloarthropathy Study Group Classification: Criteria for Spondyloarthropathy

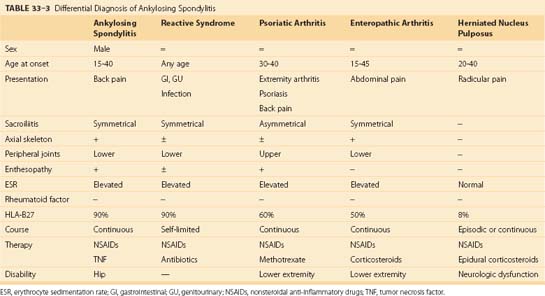

Although spondyloarthropathies are a common inflammatory musculoskeletal disorder, this group of illnesses is frequently overlooked by nonrheumatologists. A delay in diagnosis from the onset of symptoms and referral to a rheumatologist ranged from 6 to 264 months. Individuals who are misdiagnosed by primary care physicians have mild to moderate disease, with atypical presentations, and are women.25 The differential diagnosis of spinal pain includes other spondyloarthropathies and herniated intervertebral disc. Characteristics of these specific diseases are listed in Table 33–3. The inflammatory disorders are discussed briefly here.

Psoriatic Arthritis

Patients with psoriasis who develop a characteristic pattern of joint disease have psoriatic arthritis.26 The prevalence of psoriasis is 1% to 3% of the population. Classic psoriatic arthritis is described as involving distal interphalangeal joints and associated nail disease alone.27 This pattern occurs in 5% of patients. The most common form of the disease, affecting 70% of patients with psoriatic arthritis, is an asymmetrical oligoarthritis; a few large or small joints are involved. Dactylitis, diffuse swelling of a digit, is most closely associated with this form of the disease. Skin activity and joint symptoms do not correlate, and patients with little skin activity may experience continued joint pain and stiffness.

Spondylitis on radiographs is characterized by asymmetrical involvement of the vertebral bodies and nonmarginal syndesmophytes. Joint ankylosis occurs less commonly than in AS. Of patients, 25% can have sacroiliac involvement manifested by sacroiliitis, which can be unilateral or bilateral. Symmetrical involvement—from side to side and severity of disease—predominates over asymmetrical disease. Sacroiliitis may occur without spondylitis. Spinal disease progression occurs in a random rather than orderly fashion, ascending the spine as commonly noted in AS. Cervical spine disease may occur in the absence of sacroiliitis or lumbar spondylitis. Alterations in the cervical spine include joint space sclerosis and narrowing and anterior ligamentous calcification (Fig. 33–5).

Treatment of psoriatic arthritis is similar to treatment of RA. Immunosuppressive agents and TNF-α inhibitors are indicated for the treatment of peripheral arthritis.28 The benefits for axial disease are being studied. Patients with psoriatic arthritis develop varying degrees of restriction of spinal motion. There is no consistent correlation between the severity of peripheral joint and axial skeletal disease. Rarely, patients with psoriatic arthritis may develop atlantoaxial subluxation with evidence of cervical myelopathy. Fracture after minor trauma may be overlooked for an extended period.29 This disease should be treated early and aggressively.30

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree