14

Anterior Interosseous Nerve Syndrome

Michael F. Bothwell and Kevin D. Plancher

History and Clinical Presentation

A 28-year-old weight lifter presents with weakness in his ability to pinch over the last 6 months after having an interscalene block for shoulder surgery. He also reports an ache in his forearm but no other pain or numbness. The patient is an avid weight lifter but reports no specific trauma or previous history of problems in the same area.

Physical Examination

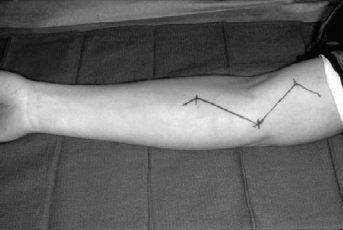

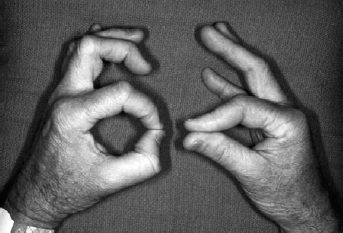

When a patient is asked to pinch, active flexion of the distal interphalangeal (DIP) index is impossible (Fig. 14–1). There is an inability to flex the interphalangeal joint of the thumb and the distal phalangeal joint of the index finger secondary to weakness of the flexor pollicis longus (FPL) and the index flexor digitorum profundus (FDP), with weakness of the pronator quadratus. A positive Tinel’s test over the proximal forearm is also seen with pain radiating distally. The patient reports intermittent pain in the proximal portion of the volar forearm, with no atrophy or sensory changes.

PEARLS

- Accurate attempt at pinch by patient is crucial to diagnosis—“OK” sign tip to tip.

- Weight lifters often have hypertrophy of the forearm muscles leading to this diagnosis.

- Complete hemostasis is essential during surgery with tourniquet, but limit time to ensure speedy recovery.

PITFALLS

- Inaccurate diagnosis can lead to unnecessary surgery.

- Understanding anatomy in the forearm is crucial to successful recovery.

- Position of the patient’s neck in shoulder surgery should be monitored by the anesthesiologist and surgeon.

Differential Diagnosis

- Isolated rupture of the flexor pollicis longus (FPL)

- Rupture of the index flexor digitorum profundus (FDP)

- Laceration of the nerve

- Tumor of the forearm

- Anterior interosseus nerve palsy

Figure 14–1. Typical pinch sign with flattening of index pulp and classic palsy of the anterior interosseous nerve with “ok” sign on left hand.

Diagnostic Studies

Electromyogram (EMG) will confirm the diagnosis of anterior interosseous nerve syndrome (AINS) in most cases if the test is focusing on the individual muscles, FPL/FDP index, and pronator quadratus. Nerve conduction tests are often normal. X-rays should also be taken to ensure there is no underlying cause or fracture.

Diagnosis

Anterior Interosseous Nerve Palsy

Kiloh and Nevin first described AINS in 1952. It is seen sporadically in athletes resulting from a violent muscle contracture from aggressive forearm exercises. Trauma and structural anomalies can also cause AINS. Isolated AINS also may be seen in acute brachial neuritis caused by sports or postanesthesia from an interscalene block. Anatomically, it is caused by the compression of the anterior interosseous branch of the median nerve by fibrous bands from the deep head of the pronator teres or flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS), anomalous vessels or muscles, flexor carpi radialis brevis, or palmaris profundus. Its origin is usually 5 cm below the level of the medial epicondyle. It travels through the forearm distally with the median nerve. It gives off a motor branch to the FPL. The anterior interosseous nerve exclusively innervates the FDP to the index finger, whereas the FDP to the middle finger is innervated by the anterior interosseous nerve 50% of the time, escaping paralysis. This syndrome has been reported in various types of athletes such as baseball pitchers, tennis players, gymnasts, weight lifters, and football players.

Nonsurgical Management

Treatment of anterior interosseous nerve palsy should be based on the specific etiology. Conservative treatment consisting of ice, rest, and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) should continue for 8 to 12 weeks before surgery becomes an option. Some authors have recommended continued nonsurgical treatment for longer periods of time up to 6 months. A postanesthetic acute brachial neuritis of the anterior interosseous nerve (AIN) should be given at least 4 months of conservative treatment before surgery becomes an option. There have been documented cases of return up to 18 months after onset. It has been noted that the return in such cases is often unpredictable, and there has not been total recovery.

Surgical Management

Surgical decompression offers a more rapid recovery in most cases. If there is no clinical or EMG improvement in the 8- lumen, 12-week period after injury, surgical exploration should be undertaken.

Surgical exploration consists of identifying the median nerve from the proximal forearm and following the AIN distally, identifying all its branches on the way (Fig. 14–2). The incision should start ∼5 cm above the medial epicondyle. It extends distally over the medial flexor muscle mass (Fig. 14–3A). The median nerve is identified proximal medial to the brachial artery. It is followed distally to the superficial head of the pronator teres. The pronator teres is mobilized and separated from the flexor carpi radialis, allowing exposure of the nerve. The nerve is exposed where it emerges from beneath the fibers of the flexor digitorum sublimis. The nerve is traced proximally by retracting the flexor carpi radialis laterally and pronator proximally and by separating the fibers of the flexor digitorum sublimis (Fig. 14–3B). The nerve is then exposed over its course. The AIN emerges from the posteromedial side of the nerve after passing through the two heads of the pronator teres and supplies the FPL, the radial half of the flexor profundus, and the pronator quadratus (Fig. 14–4). In most cases, the median and anterior interosseous nerves pass through the superficial and deep heads of the pronator teres (Fig. 14–5).