aA background infusion rate is not recommended for opioid-naïve patients.

bMeperidine limit in healthy patients should be 800 mg in first 24 h and then 600 mg every 24 h thereafter.

The adverse effects of opioid administration can cause serious complications in patients undergoing major orthopaedic procedures. In a systematic review, Wheeler et al.23 reported gastrointestinal effects (nausea, vomiting, ileus) in 37%, cognitive effects (somnolence and dizziness) in 34%, pruritus in 15%, urinary retention in 16%, and respiratory depression in 2% of patients receiving PCA opioid analgesia.

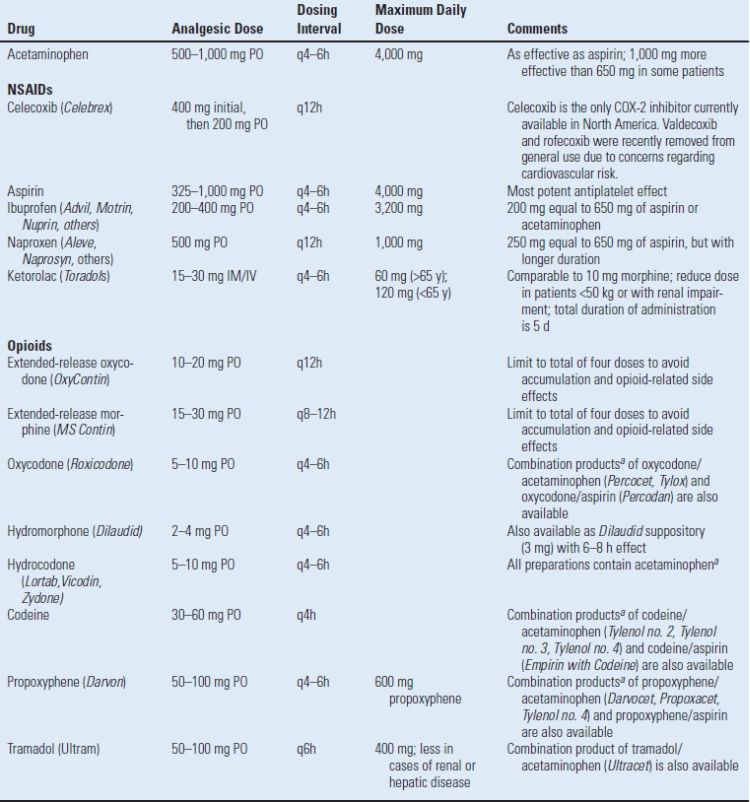

Oral opioids (Table 1.2) are available in immediaterelease and controlled-release formulations. Although immediate-release oral opioids are effective in relieving moderate to severe pain, they must be administered as often as every 4 hours. When these medications are prescribed “as needed” (prn), there may be a delay in the administration and a subsequent increase in pain. Furthermore, interruption of the dosing schedule, particularly during the night, may lead to an increase in the patient’s pain. The United States Acute Pain Management Guideline Panel currently recommends a fixed dosing schedule for all patients requiring opioid medications for more than 48 hours postoperatively (AHCPR Pub No 92-0032). The adverse effects of oral opioid administration are considerably less compared to those of intravenous administration, and are mainly gastrointestinal in nature.23

TABLE 1.2 Oral Analgesics

aDose in combination products limited by total acetaminophen or aspirin ingestion.

PO, orally; IM, intramuscularly; IV, intravenously.

A controlled-release formulation of oxycodone (OxyContin) is also available and has been shown to provide therapeutic opioid concentrations and sustained pain relief over an extended time period. Combined with prn oxycodone for breakthrough pain, scheduled administration of controlled-release oxycodone maximizes the analgesia and decreases the associated side effects.24

Tramadol (Ultram) is a centrally acting analgesic that is structurally related to morphine and codeine (but is not truly an opioid). Its analgesic effect is through binding to the opioid receptors as well as blocking the reuptake of both norepinephrine and serotonin. Tramadol has gained popularity due to the low incidence of adverse effects, specifically respiratory depression, constipation, and abuse potential. Thus, tramadol may be used as an alternative to opioids in a multimodal approach to postoperative pain, specifically in patients who are intolerant to opioid analgesics.

Nonopioid Analgesics (Acetaminophen and Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs). The addition of nonopioid analgesics reduces opioid use, improves analgesia, and decreases opioid-related side effects. The multimodal effect is maximized through selection of analgesics that have complementary sites of action. For example, acetaminophen acts predominantly centrally, while other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) exert their effects peripherally.

The mechanism of analgesic action of acetaminophen has not been fully determined. Acetaminophen may act predominantly by inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis in the central nervous system. Acetaminophen has very few adverse side effects and is an important addition to the multimodal postoperative pain regimen, although the total daily dose must be limited to <4,000 mg. It is also important to note that many oral analgesics are an opioid-acetaminophen combination. In these preparations, the total dose of opioid will be restricted to the acetaminophen ingested.

The NSAIDs have a mechanism of action through the cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymatic pathway and ultimately block two individual prostaglandin pathways. The COX-1 pathway is involved in prostaglandin E2–mediated gastric mucosal protection and thromboxane effects on coagulation. The inducible COX-2 pathway is mainly involved in the generation of prostaglandins included in the modulation of pain and fever but has no effect on platelet function or the coagulation system. In general, NSAIDs block both the COX-1 and COX-2 pathways. Traditionally, NSAIDs have been viewed as peripherally acting agents. However, there may be a central analgesic effect through inhibition of spinal COX.

The introduction of specific COX-2 inhibitors represented a breakthrough in the treatment of pain and inflammation. However, despite their efficacy, two COX-2 inhibitors (rofecoxib [Vioxx]; valdecoxib [Bextra]) were voluntarily removed from general use due to an increased relative risk for confirmed cardiovascular events, including heart attack and stroke, after 18 months of treatment. Celecoxib (Celebrex) is currently the only COX-2 inhibitor available in the United States although the Food and Drug Administration has requested that safety information be included regarding potential cardiovascular and gastrointestinal risks of all selective and nonselective NSAIDs except aspirin.25

Although numerous NSAIDs have been used in the perioperative management of pain, ketorolac is the only NSAID that can be given parenterally. An intravenous dose of ketorolac 10 to 30 mg was found to have a similar efficacy to that of 10 to 12 mg of intravenous morphine. In surgical patients, ketorolac reduces opioid consumption by 36%. Due to the potential for serious side effects, ketorolac should be used for 5 days or less in the adult population with moderate to severe acute pain.26

The major side effects limiting NSAID use for postoperative pain control (renal failure, platelet dysfunction, and gastric ulcers or bleeding) are related to the nonspecific inhibition of the COX-1 enzyme.26 Advantages of the COX-2 inhibitors are the lack of platelet inhibition and a decreased incidence of gastrointestinal effects. All NSAIDs have the potential to cause serious renal impairment. Inhibition of the COX enzyme may have only minor effects in the healthy kidney but unfortunately can lead to serious side effects in elderly patients or those with a low-volume condition (blood loss, dehydration, cirrhosis, or heart failure). Therefore, NSAIDs should be used cautiously in patients with underlying renal dysfunction, specifically in the setting of volume depletion due to blood loss.26 Similar to the COX-2 inhibitors, NSAIDs also interfere with the inhibitory COX-1 effect of aspirin on platelet activity and may counter the cardioprotective effects.27

The effect of NSAIDs on bone formation and healing is of concern to the orthopaedic population. Although the data are conflicting, there is evidence from animal studies that COX-2 inhibitors may inhibit bone healing.28 Thus, the adverse effects of COX-2 inhibitors must be weighed against the benefits. Until definitive human trials are performed, it is reasonable to be cautious with the use of COX-2 inhibitors, especially when bone healing is critical.

Neuraxial Analgesia A variety of single-dose and continuous infusion neuraxial techniques may be performed to provide analgesia following revision arthroplasty. Administration of a single dose of neuraxial opioid may be efficacious as a sole analgesic agent for moderate pain of limited duration, such as that associated with primary hip arthroplasty.29 However, the prolonged moderate-severe pain associated with many revision arthroplasties typically necessitates either supplemental oral or intravenous analgesic agents or a continuous neuraxial infusion.

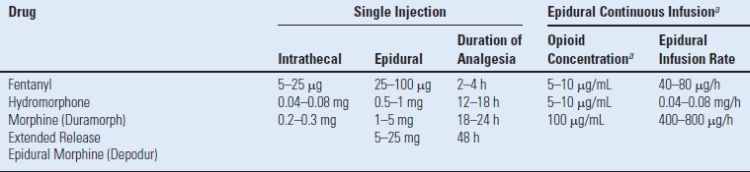

Single-dose Spinal and Epidural Opioids. Neuraxial opioids provide superior analgesia compared to systemic opioids. The onset and duration of neuraxial opioids are determined by the lipophilicity of the drug. For example, lipophilic opioids, such as fentanyl, provide a rapid onset of analgesia, limited spread within the cerebrospinal fluid (and less respiratory depression), and rapid clearance/resolution. Conversely, hydrophilic opioids, including morphine and hydromorphone, have a longer duration of action but are associated with a higher frequency of side effects such as pruritus, nausea and vomiting, and delayed respiratory depression (Table 1.3). A new sustained-release formulation of epidural morphine (Depodur) has recently been released. Limited information exists regarding its efficacy following orthopaedic surgery.30 The analgesic effect is present for approximately 48 hours. Unfortunately, Depodu is not to be administered in the presence of local anesthetics (i.e., an epidural anesthetic may not be converted to provide epidural analgesia). It is important to note that the central side effects of opioid administration are much more common (and more prolonged) following neuraxial administration compared to all other routes. For example, in a large series, the frequencies of pruritus, nausea, vomiting, and respiratory depression were 37%, 25%, and 3%, respectively, with an intrathecal morphine injection.31 Therefore, patients who exhibit sensitivity to an opioid when administered systemically should not receive that opioid neuraxially.

TABLE 1.3 Dosing Regimens for Neuraxial Opioids

Note that units vary across agents for single dosing (μg, mg).

a Epidural solutions for major orthopaedic surgery are typically local anesthetics (ropivacaine 0.2% or bupivacaine 0.0625%–0.125%) with an opioid adjuvant. Only preservative-free solutions may be utilized.

b The concentration of the opioid is selected to achieve an infusion rate of 6–10 mL/h. Lower infusion rates may not deliver adequate analgesia, while higher infusion rates will be associated with motor block and inability to ambulate.

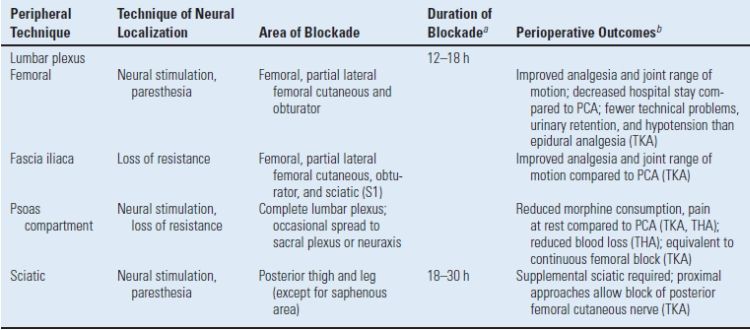

Epidural Analgesia. Epidural analgesia may consist of an opioid, local anesthetic, or combination local anestheticopioid infusion (Table 1.4). The combination of a local anesthetic-opioid creates a synergistic analgesic effect and allows lower concentrations of each component of the solution. For example, without an opioid adjuvant, the concentration of a local anesthetic solution may be sufficiently high to result in a dense sensory and motor block; the patient may be unable to ambulate or void.32 Likewise, a pure opioid epidural infusion may not provide adequate analgesia.33 As a result, most epidural solutions consist of dilute concentrations of both local anesthetic and opioid. This results in superior analgesia, minimal sensory and motor block (allowing ambulation and mobilization), and decreased incidence of opioid-related side effects (nausea/vomiting and pruritus).19,20 Although epidural analgesia provided excellent analgesia, the associated risk of spinal hematoma in (anticoagulated) patients with indwelling epidural catheters led to a search for alternative methods of providing postoperative analgesia following major orthopaedic surgery.

TABLE 1.4 Peripheral Regional Analgesic Techniques for Major Hip and Knee Surgery

aDuration of block performed with long-acting local anesthetic (bupivacaine or ropivacaine); intermediate-acting agents (lidocaine or mepivacaine) will resolve after 4–6 h.

bOutcomes most marked in patients who receive a continuous lumbar plexus catheter with infusion of 0.1%–0.2% bupivacaine or ropivacaine at 6–12 mL/h for 48–72 h.

TKA, total knee arthroplasty; THA, total hip arthroplasty; PCA, patient-controlled analgesia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree