Anatomy of the Proximal Femur

Martin Beck

Lorenz Büchler

Reinhold Ganz

Michael Leunig

Development of the Proximal Femur after Birth

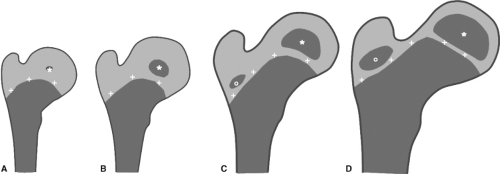

At birth the greater trochanter and femoral head share a common physis. During growth the medial part of the physis evolves into the physis of the femoral head and the lateral part becomes the physis of the greater trochanter (Fig. 6.1). The separation of the common physis into two distinct ones occurs at the age of 4. The physis of the femoral head is responsible for the development of the femoral neck. The growth of the neck occurs on the metaphyseal side of the physis, contributing to most of the length of the femoral neck. This is in contrast to the greater trochanter, where appositional growth at the periphery contributes to the size of the greater trochanter (1). Incomplete separation of the common physis may lead to widening of the femoral neck in the anterosuperior area that eventually may predispose to a femoroacetabular impingement of the cam type (2).

The center of ossification in the femoral head appears in females at the age of 4 to 7 months and in males at the age of 5 to 8 months. The ossification center of the greater trochanter develops generally at the age of 4 years. The ossification center in the lesser trochanter appears only much later at 12 to 14 years. Closure of the femoral head physis occurs at an age of approximately 18 years; the physis of the greater trochanter closes earlier at the age of 16 to 18 years (3,4).

Bony Anatomy

Antetorsion

The femoral neck antetorsion is the inclination of the axis of the femoral neck with reference to a line placed on the posterior contour of the femoral condyles. If the axis of the neck inclines forward the angle of torsion is called antetorsion. Similarly, if it points backward it is called retrotorsion. The normal values for children and adults differ considerably in the available literature. Different techniques of examination as well as different populations may explain the different results (5,6). On average, femoral anteversion ranges from 30 to 40 degrees at birth and decreases progressively throughout growth. According to Svenningsen et al. (7) femoral antetorsion has a regression rate of about 1.5 degrees (range: 0.2 to 3.1 degrees) per year. In the adult femoral antetorsion averages 10.5 degrees, however, with a

high standard deviation of ±9.22 degrees (8). Antetorsion increases the range of free hip flexion and internal rotation; however, it decreases external rotation in extension. Both increased femoral antetorsion and retrotorsion have been attributed with early degenerative joint disease (9,10,11).

high standard deviation of ±9.22 degrees (8). Antetorsion increases the range of free hip flexion and internal rotation; however, it decreases external rotation in extension. Both increased femoral antetorsion and retrotorsion have been attributed with early degenerative joint disease (9,10,11).

Neck–Shaft Angle

The neck–shaft angle is normally measured on anteroposterior (AP) radiographs as the angle formed by the axis of the femur and the axis of the neck going through the center of the femoral head. Projected values are largely influenced by the rotation of the femur. The normal neck–shaft angle measures 125 degrees (12,13). In an overview of the literature, Clarke et al. (14) found a high variability with values ranging between 121.4 and 137.5 degrees. Yoshioka et al. (15) reported higher values with an average of 129 degrees (±7.3 degrees) for males and 133 degrees (±6.6 degrees) for females. The difference in this study can be explained with the technique of measurement. Generally, the femoral axis is placed in the center of the radiographically visible proximal femur. Yoshioka et al., however, defined the axis of the femoral shaft by the center of the shaft at the subtrochanteric area and the origin of the posterior cruciate ligament. Higher values were also measured on radiographs (128.7 ± 7.2 degrees) compared to anatomical measurements (123 ± 6.8 degrees) in the same specimen (14).

In another study the position of the tip of the greater trochanter was measured in relation to the center of rotation in 225 radiographs of hips scheduled for a hip replacement. The average location of the tip of the greater trochanter was 3.4 ± 0.9 mm superior to the center of rotation (ranged from 20 mm superior to 10 mm inferior to the femoral head center). In one-third of the hips the tip of the greater trochanter was within 1 mm above or below the center of rotation and within 5 mm in approximately half of the hips (16).

Lesser Trochanter

The lesser trochanter is positioned at a retrotorsion angle (α) of -31.5 degrees with a standard deviation of ±11.8 degrees (8). In the same study an average antetorsion of the femoral neck (β) of 10.5 ± 9.22 degrees was found. There was a high correlation between the antetorsion of the neck and the retrotorsion of the lesser trochanter. The angle between the two torsions follows the equation β = 29.5 + 0.6α.

Shape of the Femoral Neck

The femoral neck is oval in shape. The orientation of the greatest diameter of the femoral neck relative to the mechanical long axis of the femur is defined with the angle ρ (rho). Angle ρ was reported to measure in a normal hip 21 ± 9 degrees and in hips with an aspheric head–neck junction 25 ± 8 degrees; the difference is not significant (17). As a consequence of the oval cross section the modified alpha angle is reduced in the anterosuperior area of the head–neck junction and can add to cam-type femoroacetabular impingement. A gender difference was observed, with males having a significantly more prominent head–neck junction anterosuperiorly (6).

Position of the Femoral Head on the Neck

Besides the common measurements including femoral torsion and neck–shaft angle, the position of the femoral head on the neck was determined in an extensive study on cadaveric femora (18). The position of the femoral head can be defined with the following three parameters:

Femoral head offset: Femoral offset is measured at four locations: superior, inferior, anterior, and posterior.

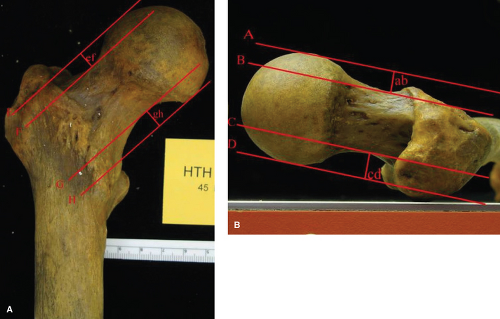

A line is drawn parallel to the neck axis and tangential to the convexity of the femoral head. A second line is drawn parallel to the first tangential to the cavity of the femoral neck. Femoral head–neck offset is the perpendicular distance between these two lines (19). The ratio between the superior/inferior offset and anterior/posterior offset indicates the relative position of the femoral head (Fig. 6.2A,B).

Alpha angle: The alpha angle was first described by Nötzli et al. (20) as an indicator of femoral head–neck asphericity. The alpha angle is the acute angle between the neck axis and a line connecting the center of rotation with the point where the femoral head exits a circle around the femoral head. The alpha angle measures the anterior asphericity; however, the individual maximum value can be best determined with radial cuts of an MRI. Likewise, yet of less importance, the beta angle is measured posteriorly, the gamma angle superiorly, and the delta angle inferiorly (Fig. 6.3A,B) (18). Based on several studies the normal alpha angle is between 43 and 50 degrees (20,21,22).

Head–neck rotation: Rotation or tilt of the femoral head has been defined as the deviation from the optimal position where the axis of the femoral head and the neck are in line (18). In most hips there is some degree of tilt in the physeal scar. This rotational movement can be measured with the so-called physeal angles. The AP physeal angle was defined as the superior-lateral angle between the intersection of the femoral neck axis and a line representing the physeal scar in the AP pictures (Fig. 6.4A). Similarly, the lateral physeal angle is defined as the anterior-lateral angle made between these same lines in the orthogonal, lateral view (Fig. 6.4B). Femoral heads with AP and/or lateral physeal angles equal to 90 degrees would not be rotated with respect to the neck axis. However, femoral heads with AP and/or lateral physeal angles greater than 90 degrees would be adducted and/or retroverted, whereas femoral heads with AP and/or lateral physeal angles less than 90 degrees would be abducted and/or anteverted.

On average, the femoral head tends to be translated anteriorly and inferiorly, rotated in abduction and anteversion, and has a greater concavity posteriorly and inferiorly. The femoral head–neck junction has greater concavity posteriorly and inferiorly than anteriorly and superiorly (Table 6.1).

Regarding translation, males have on average more inferior offset than females. Regarding rotation males have on average more abduction and anteversion than females. Regarding concavity males and those older than 50 years have less concavity of the anterior head–neck junction than females and those younger than 50 years (Table 6.2).

Fovea Capitis Femoris

The fovea capitis femoris is an ovoid depression, which is situated a little inferior and posterior to the center of the head, and gives attachment to the ligamentum teres (23). In normal hips the average angle from the cranial extension of the fossa acetabuli to the cranial extension of the fovea measures 26 degrees (24). In dysplastic hips the fovea is wider and on average 30 degrees more cranial, touching the weight-bearing area. This “fovea alta” is characteristic for the dysplastic hip. The overlap of the weight-bearing area and the “fovea alta” may give rise to an internal impingement of the ligamentum teres against the rim of the fossa acetabuli.

The Blood Supply of the Growing Proximal Femur

In the adult the vascular blood supply of the femoral head is secured through the retinacular arteries from the deep branch of the medial femoral circumflex artery (MFCA) (25,26,27,28). The evolution of the blood supply to the femoral head and proximal femur depends largely on the development of the

growth plates and growth of femoral neck and greater trochanter. The following paragraph summarizes the few publications on the blood supply of the growing proximal femur (29,30,31,32,33). In the work of Ogden (31) only children between 0 and 3 years were examined but Trueta (32) and Chung (29) covered the entire growth period until the end of adolescence.

growth plates and growth of femoral neck and greater trochanter. The following paragraph summarizes the few publications on the blood supply of the growing proximal femur (29,30,31,32,33). In the work of Ogden (31) only children between 0 and 3 years were examined but Trueta (32) and Chung (29) covered the entire growth period until the end of adolescence.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree