Anatomic Double-Bundle ACL Reconstruction

James R. Romanowski

T. Thomas Liu

Freddie H. Fu

INTRODUCTION

Anterior cruciate ligament injuries remain one of the most common injuries facing orthopaedic surgeons today. Approximately 100,000 ACL reconstructions are performed each year, the majority (85%) of which are performed by surgeons who reconstruct ≤10 annually (4,5,7). The prevalence of the injury has subsequently led to the focus of significant resources on research and improving the clinical outcome. Even though single-bundle reconstruction techniques have enjoyed relatively successful outcomes, shortcomings inherent to the surgical technique remain. Success rates are often reported in the 80% to 90% range; however, good-to-excellent results are limited to approximately 60% of patients (1). Surgical technique is considered the most common cause of ACL failure. Therefore, it is imperative to consider the four principles of anatomic double-bundle ACL reconstruction: (a) anatomic tunnel placement, (b) restoration of the two functional bundles of the ACL, (c) proper tensioning of each bundle, and (d) individualized reconstruction (Table 30.1) (7,8,14).

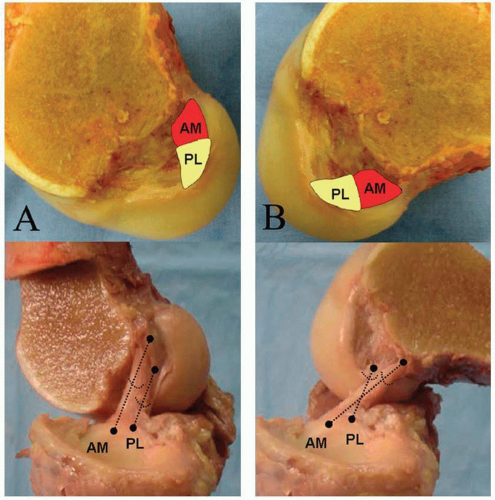

The anterior cruciate ligament comprises two bundles—the anteromedial (AM) and the posterolateral (PL) (Fig. 30.1) (2). One of the biggest advances over the past few decades has been the improved understanding in the anatomy of the ACL as well as the kinematic contributions of each bundle. Depending on the position of the knee, these individual bundles exhibit variable tension. The AM bundle experiences the greatest tension during flexion with corresponding laxity of the PL bundle. As the knee extends, the PL bundle increases tension with subsequent laxity of the AM component. Particularly interesting is the trend toward “anatomic” reconstruction. Anatomic reconstruction is a concept that is applicable to both single- and double-bundle approaches with the goal remaining the same—improved patient outcomes. Central to the concept of anatomic ACL reconstruction is the fact that every patient’s anatomy is unique. One of the primary tenants of orthopaedic surgery is anatomy and surgical intervention seeks to repair or replicate the native structure.

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

Patients with symptomatic ACL tears or dysfunction are candidates for single- or double-bundle ACL reconstruction. Symptoms typically are related to instability rather than pain. Cutting- or pivoting-type activities are commonly associated with the knee “giving out.” This population generally involves high-level athletes or individuals with physically demanding employment or activities that require stability of the injured joint. Age is not a contraindication, but rather the presence of open growth plates in younger patients and cartilage wear in older

populations may preclude surgical intervention. For sedentary or asymptomatic individuals, a conservative approach should be employed. A relative contraindication to double-bundle approaches is the presence of open growth plates. Other criteria that prompt single- rather than double-bundle reconstruction include narrow femoral notch, small insertion sites, and significant lateral femoral condyle contusion (discussed in more detail later in this chapter). Absolute contraindications include active infection, end-stage multicompartmental arthritis, or unwillingness to cooperate with the postoperative restrictions and rehabilitation.

populations may preclude surgical intervention. For sedentary or asymptomatic individuals, a conservative approach should be employed. A relative contraindication to double-bundle approaches is the presence of open growth plates. Other criteria that prompt single- rather than double-bundle reconstruction include narrow femoral notch, small insertion sites, and significant lateral femoral condyle contusion (discussed in more detail later in this chapter). Absolute contraindications include active infection, end-stage multicompartmental arthritis, or unwillingness to cooperate with the postoperative restrictions and rehabilitation.

TABLE 30.1 Principles of Anatomic Double-Bundle Reconstruction | |

|---|---|

|

PATIENT EVALUATION

Critical to the success of ACL reconstruction surgery is a thorough patient evaluation. The history provides details that can help direct the physical exam. Injuries may either be from direct trauma or noncontact maneuvers such as a low-energy pivot or twist during landing. Varus- or valgus-type injuries may suggest associated damage to the LCL or MCL, respectively. Meniscal damage should be suspected when complaints focus on mechanical symptoms such as locking or catching. Patients typically describe a “pop” with a joint effusion within the first 24 to 48 of injury. For patients who attempt return to play or other functional demands, continued instability symptoms usually manifest as the knee “giving out” with pivoting or deceleration.

Physical examination begins with exposure of both lower extremities to allow for comparison. Overall alignment is documented as extremes in varus or valgus may compromise the ACL reconstruction outcome if not

addressed. A posttraumatic effusion alone is common and is strongly suggestive of intra-articular derangement, particularly of the ACL. Quadriceps atrophy is common. Ecchymosis is uncommon, but if present should be carefully evaluated for additional injuries. Bony prominences, the patellofemoral articulation, and medial and lateral joint lines are palpated with tenderness suggestive of fractures, patella dislocation, and/or meniscal pathology. ACL-directed exam maneuvers include the pivot shift, Lachman, and anterior drawer test. The pivot shift is the most sensitive of physical exam tests, but also the most difficult to perform as effusion, pain, and muscle spasm often are factors during the acute presentation (10). Additional exam maneuvers can help rule out additional ligamentous or meniscal damage including the McMurray, posterior drawer, reverse pivot shift, and Dial tests, along with varus/valgus stress testing at 0 and 30 degrees of flexion. Deficiencies found on physical exam are subjective and examiner dependent; therefore, more objective measures are available, such as an arthrometer. When used for the ACL, side-to-side differences >3 mm are suggestive of a tear. The range of motion should be evaluated and deficiencies are indications for preoperative physical therapy with modalities that focus on inflammation control, motion, and quadriceps strengthening.

addressed. A posttraumatic effusion alone is common and is strongly suggestive of intra-articular derangement, particularly of the ACL. Quadriceps atrophy is common. Ecchymosis is uncommon, but if present should be carefully evaluated for additional injuries. Bony prominences, the patellofemoral articulation, and medial and lateral joint lines are palpated with tenderness suggestive of fractures, patella dislocation, and/or meniscal pathology. ACL-directed exam maneuvers include the pivot shift, Lachman, and anterior drawer test. The pivot shift is the most sensitive of physical exam tests, but also the most difficult to perform as effusion, pain, and muscle spasm often are factors during the acute presentation (10). Additional exam maneuvers can help rule out additional ligamentous or meniscal damage including the McMurray, posterior drawer, reverse pivot shift, and Dial tests, along with varus/valgus stress testing at 0 and 30 degrees of flexion. Deficiencies found on physical exam are subjective and examiner dependent; therefore, more objective measures are available, such as an arthrometer. When used for the ACL, side-to-side differences >3 mm are suggestive of a tear. The range of motion should be evaluated and deficiencies are indications for preoperative physical therapy with modalities that focus on inflammation control, motion, and quadriceps strengthening.

Radiographs are necessary for the evaluation of the acutely injured knee. Besides ruling out fractures, x-rays can assess overall limb alignment, joint space narrowing, prior hardware, and more subtle findings such as a Segond fracture suggestive of an ACL tear. For younger patients, particular attention toward the growth plates is necessary as this affects preoperative planning. Standard films include a full-length cassette of the bilateral lower extremities, 45-degree non-weight-bearing lateral, weight-bearing extension, and 45-degree flexion posteroanterior x-rays, and merchant views of the bilateral patellofemoral joints.

The majority of patients who present for evaluation have already had an MRI performed that can help verify the ACL rupture as well as study the knee for additional injuries. Although MRI is not necessary, it can provide valuable insight during the preoperative planning period. Specific MRI protocols have been developed that focus on the ACL as a double-bundle structure and can identify not only full-thickness ACL tears but also isolated bundles ruptures that may affect the surgical reconstruction.

More recently, computed axial tomography scans protocols that include three-dimensional reconstructions have been developed to allow for valuable information regarding bony architecture, bone loss, and tunnel positioning related to prior surgical intervention. This modality is rarely needed during the workup of the primary ACL tear but can be invaluable in determining single versus staged revision reconstruction of an ACL tear.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Once it has been decided to perform an ACL reconstruction, important consideration should be given toward the surgical timing. Surgery should not be performed until three criteria are met: (a) resolution of joint effusion, (b) improvement of range of motion to 0 to 120 degrees as the risk of arthrofibrosis for acute reconstruction approaches 37% (6,15), and (c) regain of quadriceps muscle function. Satisfying these criteria will decrease the likelihood of postoperative complications.

Graft Selection

Graft selection begins with an open discussion between the surgeon and the patient concerning the advantages and disadvantages of both allograft and autograft use for ACL reconstruction. Patient demands, activity, age, and comfort with the potential risk for disease transmission and immunologic reaction to the allograft are factors that must be considered and contribute to the ultimate choice in graft. Allografts, however, eliminate donor site morbidity, allow for faster short-term recovery, and provide the increased volume of graft often necessary for double-bundle reconstruction (11). More recently, studies have reported up to a three times greater failure rate with allograft in the use of single-bundle constructs among younger and more athletic populations; therefore, graft demands must be factored into the selection process (9,12). Our practice appreciates the concerns of allograft in the young, athletic population and has actively pursued autograft sources such as the hamstrings and quadriceps tendon for reconstruction. In patients with considerable growth remaining, single-bundle hamstring autograft sources and occasionally soft tissue allograft such as the tibialis anterior are chosen to minimize the risk of growth arrest. Multiligamentous injuries are often addressed with allograft as well, given the volume of graft needed for the reconstruction. For older, more sedentary patients with symptomatic instability related to low-demand recreational or functional activities, allograft is almost universally chosen. Occasionally, patients will require only single AM or PL bundle augmentation and graft volume becomes less of an issue, allowing allograft or traditional autograft sources such as the hamstring tendons to be easily implemented. When allograft is chosen, our practice favors the use of tibialis anterior as a graft source. However, posterior tibialis, Achilles tendon, quadriceps tendon, bone-patellar tendon-bone (BPTB), and hamstring tendons may also be used. The long-term outcome of double-bundle reconstruction is unknown, but early results are encouraging (3,13). For this reason, as well as the absence of chronic anterior knee pain related to the harvest of BPTB autograft and biomechanical deficiencies related to hamstring harvest, allograft tissue is typically chosen. If a patient chooses to pursue double-bundle reconstruction but prefers to use autologous tissue only, then the quadriceps muscle is the only graft choice with enough predictable volume to satisfy this need.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Anesthesia

An anesthetic regimen is determined after a discussion between the patient, the orthopaedic surgeon, and the anesthesiologist. Typically, ultrasound-guided peripheral nerve blocks involving the femoral and sciatic nerves are employed with a “light” sedation by experienced staff. This provides satisfactory intraoperative pain control as well as decreased postoperative narcotic use, decreased nausea, and ten times less likely hospital admission (16). The operative extremity is identified in the holding area, marked “yes,” and initialed.

Exam Under Anesthesia

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree