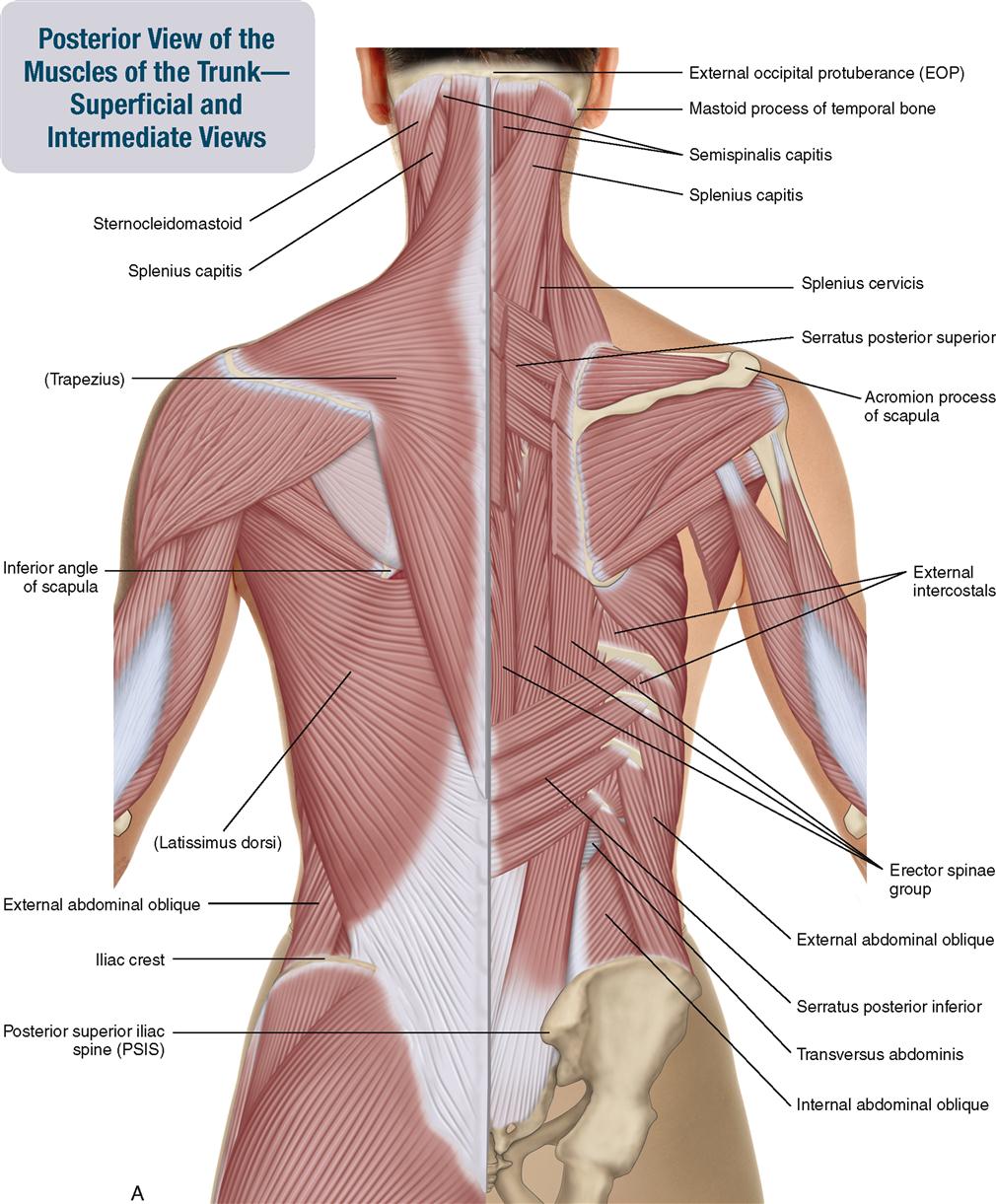

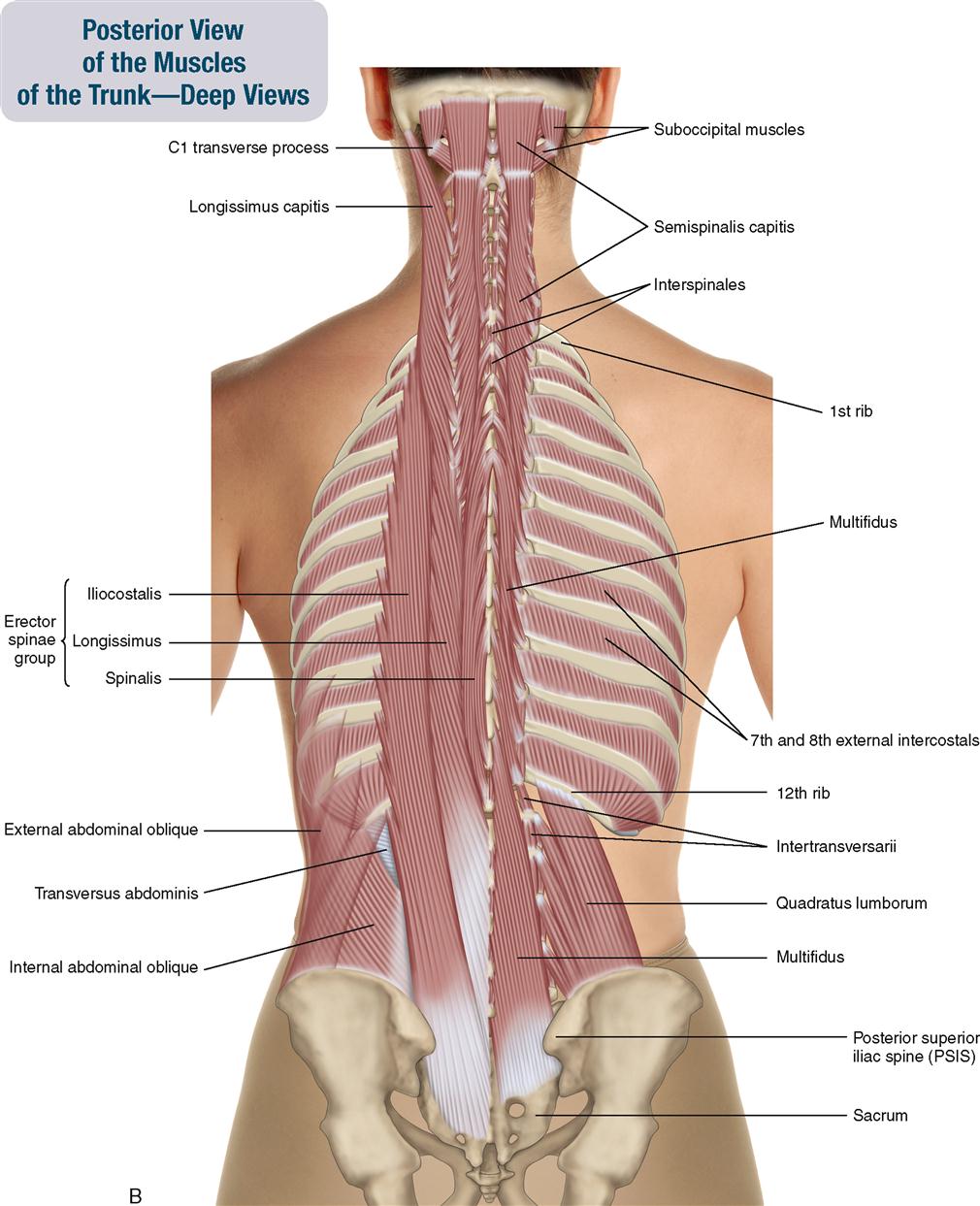

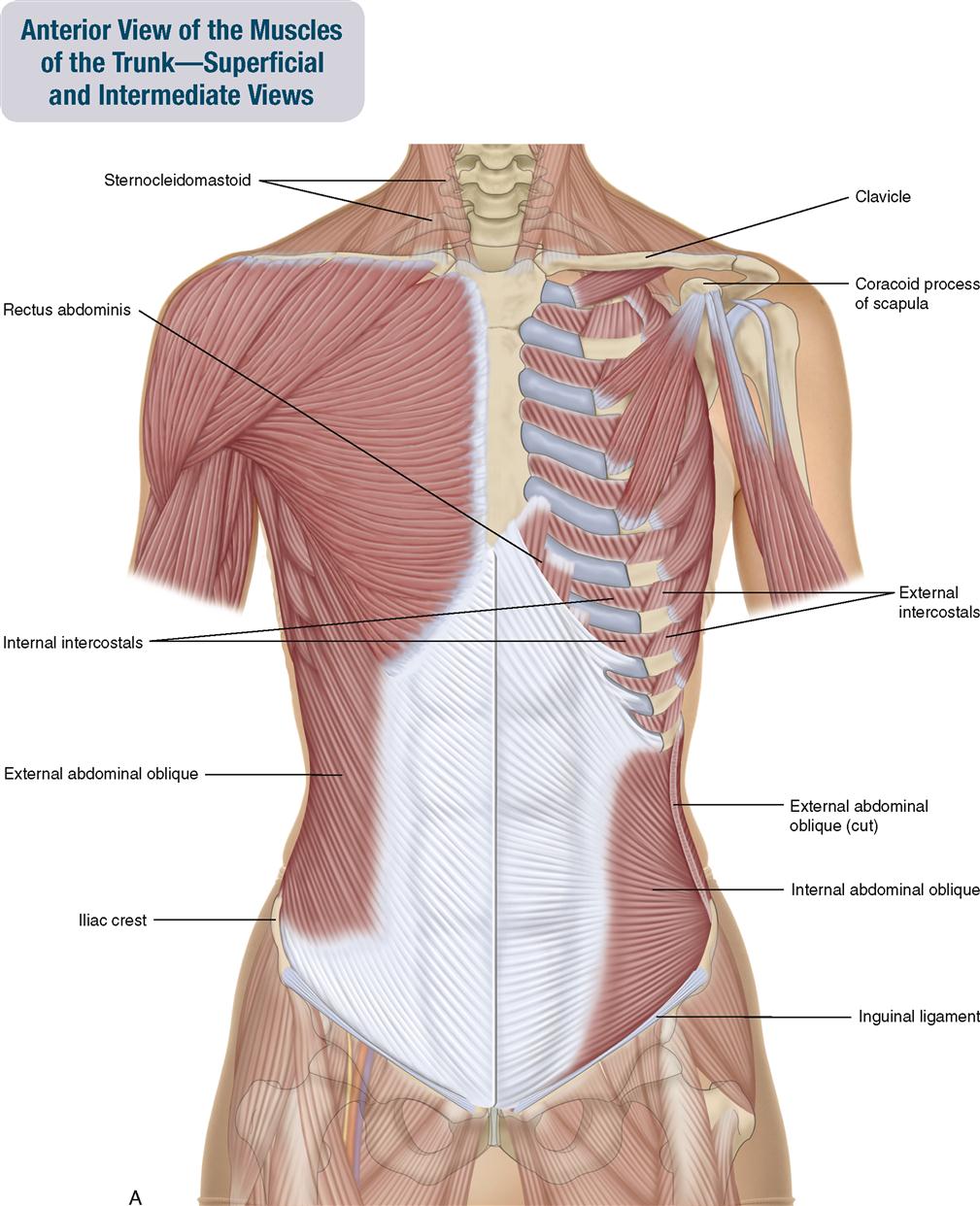

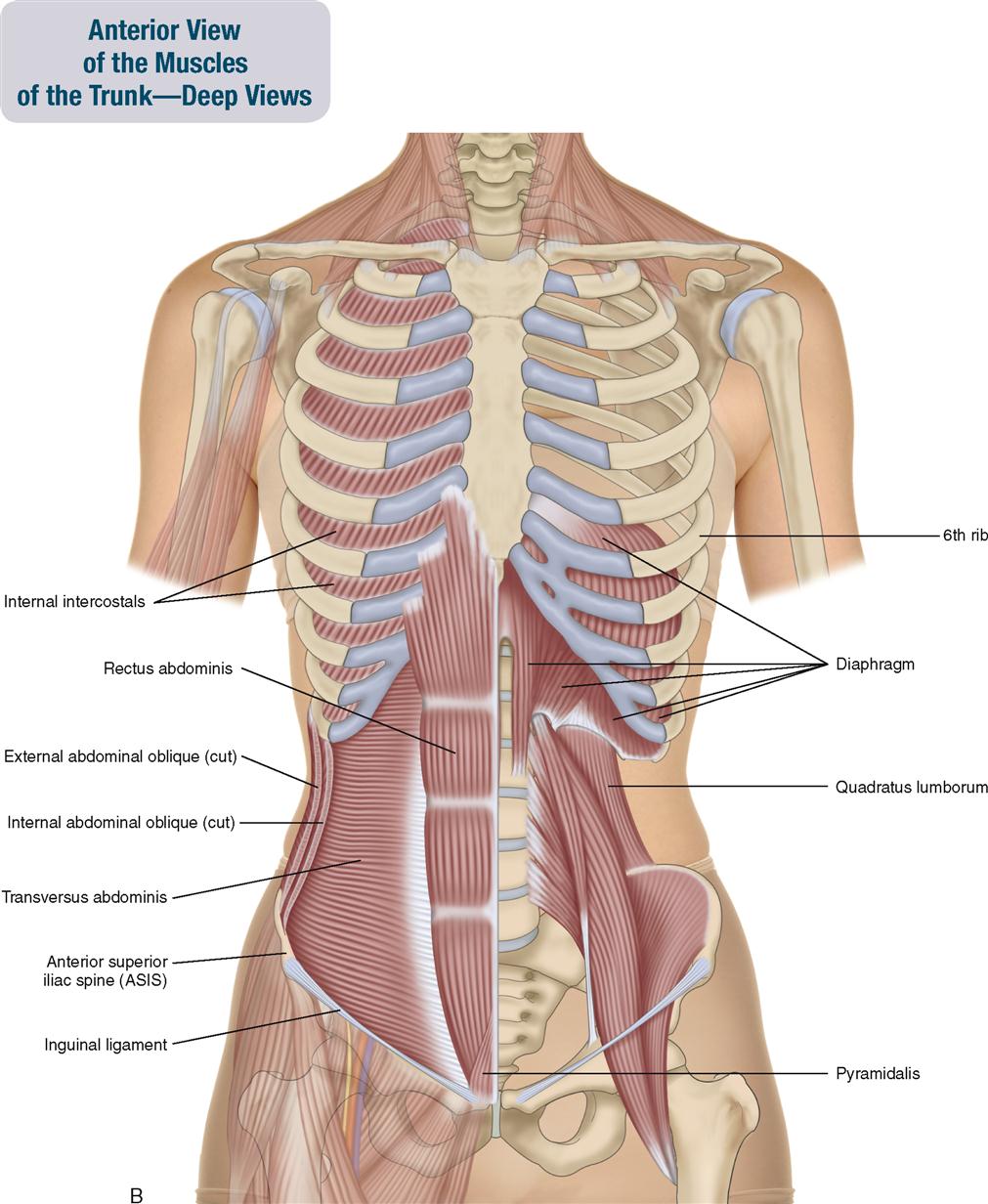

Muscles of the Spine and Rib Cage

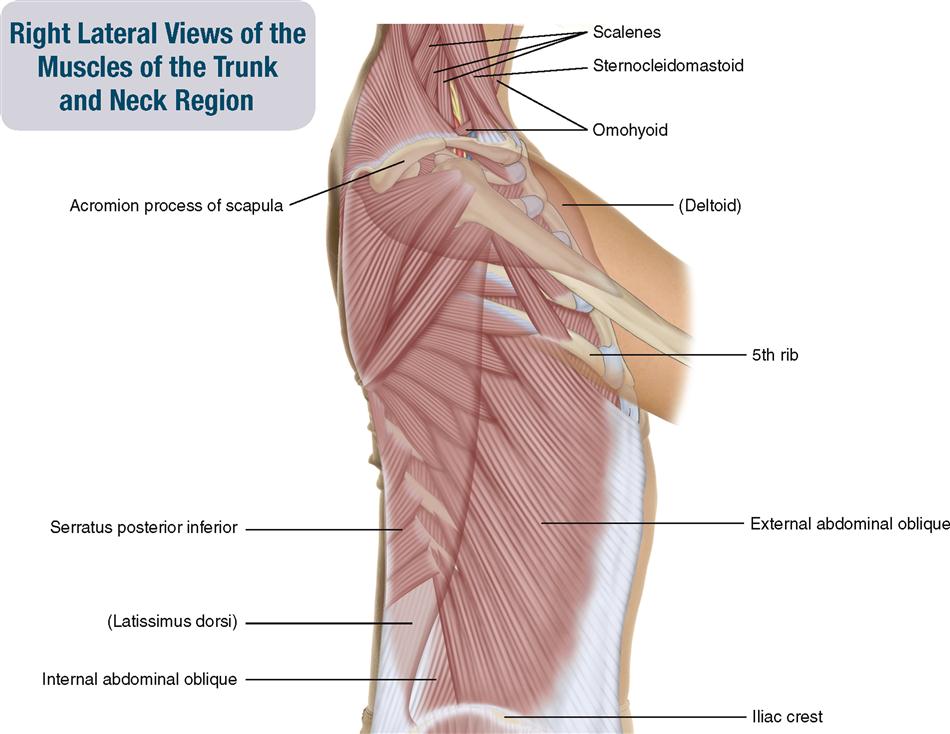

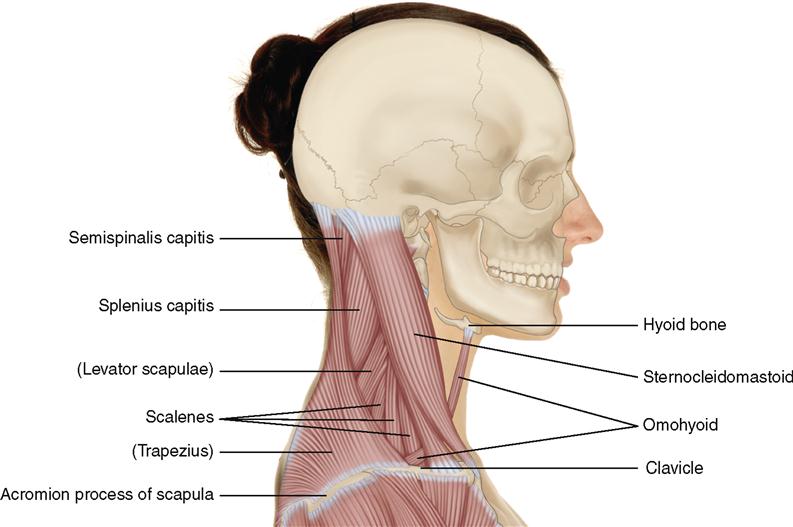

The muscles of this chapter are primarily involved with movement of the trunk, neck, and head at the spinal joints. Some of these spinal muscles can also move the mandible at the temporomandibular joints (TMJs). In addition, muscles of the rib cage are presented in this chapter. These muscles move the ribs at the sternocostal and costospinal joints.

The following is an overview of the structure and function of the spinal joint muscles presented in this chapter.

The companion CD at the back of this book allows you to examine the muscles of this body region, layer by layer, and individual muscle palpation technique videos are available in the chapter 8 folder on the Evolve website. You can find this book and other lastest musculoskeletal system books and articles by downloading Clinical Tree app. By saving content for offline access or converting it to podcast audio for convenient learning, it is perfect for medical students and professionals. Start enhancing your exam prep, presentations, or patient consultations today!

OVERVIEW OF FUNCTION: MUSCLES OF THE SPINAL JOINTS

Muscles of the spinal joints may be categorized based on three factors: (1) the region of the spine, (2) their location, and (3) their depth. Regionally, they may be divided into three groups: (1) those that run the full length of the spine, (2) those that are primarily located only in the trunk, and (3) those that are primarily located only in the neck. Regarding location, they can be described as being anterior or posterior. Regarding their depth, they can be divided based on whether they are superficial or deep. Generally, the larger, more superficial muscles of the spine are important for creating motion; and the deeper, smaller muscles function to stabilize the spine.

The following general rules regarding actions can be stated for the functional groups of muscles of the spinal joints:

If a muscle crosses the spinal joints anteriorly with a vertical direction to its fibers, it can flex the trunk, neck, and/or head at the spinal joints by moving the insertion (superior attachment) down toward the origin (inferior attachment) in front.

If a muscle crosses the spinal joints anteriorly with a vertical direction to its fibers, it can flex the trunk, neck, and/or head at the spinal joints by moving the insertion (superior attachment) down toward the origin (inferior attachment) in front.

If a muscle crosses the spinal joints posteriorly with a vertical direction to its fibers, it can extend the trunk, neck, and/or head at the spinal joints by moving the origin (superior attachment) down toward the insertion (inferior attachment) in back.

If a muscle crosses the spinal joints posteriorly with a vertical direction to its fibers, it can extend the trunk, neck, and/or head at the spinal joints by moving the origin (superior attachment) down toward the insertion (inferior attachment) in back.

If a muscle crosses the spinal joints laterally, it can perform same-side lateral flexion of the trunk, neck, and/or head at the spinal joints by moving the insertion (superior attachment) down toward the origin (inferior attachment) on that side of the body.

If a muscle crosses the spinal joints laterally, it can perform same-side lateral flexion of the trunk, neck, and/or head at the spinal joints by moving the insertion (superior attachment) down toward the origin (inferior attachment) on that side of the body.

Right and left rotators of the spine have a horizontal component to their fiber direction and wrap around the body part that they move.

Right and left rotators of the spine have a horizontal component to their fiber direction and wrap around the body part that they move.

Reverse actions of these muscles involve the lower spine (origin; inferior attachment) being moved toward the upper spine (insertion; superior attachment) at the spinal joints. These reverse actions usually occur when the client is lying down so the lower attachment is free to move. If the muscle attaches onto the pelvis, the reverse action involves movement of the pelvis at the lumbosacral spinal joint as well.

Reverse actions of these muscles involve the lower spine (origin; inferior attachment) being moved toward the upper spine (insertion; superior attachment) at the spinal joints. These reverse actions usually occur when the client is lying down so the lower attachment is free to move. If the muscle attaches onto the pelvis, the reverse action involves movement of the pelvis at the lumbosacral spinal joint as well.

The reverse action of flexion of the upper spine relative to the lower spine is flexion of the lower spine relative to the upper spine, and posterior tilt of the pelvis if the muscle attaches to it.

The reverse action of flexion of the upper spine relative to the lower spine is flexion of the lower spine relative to the upper spine, and posterior tilt of the pelvis if the muscle attaches to it.

The reverse action of extension of the upper spine relative to the lower spine is extension of the lower spine relative to the upper spine, and anterior tilt of the pelvis if the muscle attaches to it.

The reverse action of extension of the upper spine relative to the lower spine is extension of the lower spine relative to the upper spine, and anterior tilt of the pelvis if the muscle attaches to it.

The reverse action of lateral flexion of the upper spine relative to the lower spine is lateral flexion of the lower spine relative to the upper spine, and elevation of the same side of the pelvis (and therefore depression of the opposite side of the pelvis) if the muscle attaches to it.

The reverse action of lateral flexion of the upper spine relative to the lower spine is lateral flexion of the lower spine relative to the upper spine, and elevation of the same side of the pelvis (and therefore depression of the opposite side of the pelvis) if the muscle attaches to it.

The reverse action of ipsilateral rotation of the upper spine relative to the lower spine is contralateral rotation of the lower spine relative to the upper spine, and contralateral rotation of the pelvis if the muscle attaches to it.

The reverse action of ipsilateral rotation of the upper spine relative to the lower spine is contralateral rotation of the lower spine relative to the upper spine, and contralateral rotation of the pelvis if the muscle attaches to it.

The reverse action of contralateral rotation of the upper spine relative to the lower spine is ipsilateral rotation of the lower spine relative to the upper spine, and ipsilateral rotation of the pelvis if the muscle attaches to it.

The reverse action of contralateral rotation of the upper spine relative to the lower spine is ipsilateral rotation of the lower spine relative to the upper spine, and ipsilateral rotation of the pelvis if the muscle attaches to it.

OVERVIEW OF MUSCLES THAT MOVE THE MANDIBLE*

Muscles that move the mandible at the TMJs attach to the mandible. The other attachment of these muscles is usually considered to be either superior or inferior to the mandible attachment.

The following general rules regarding actions can be stated for functional groups of muscles that move the mandible:

OVERVIEW OF FUNCTION: MUSCLES OF THE RIB CAGE

Muscles that move the rib cage attach to the rib cage. The other attachment of these muscles is usually considered to be either superior or inferior to the rib attachment. These muscles may be located anteriorly, posteriorly, and/or laterally.

The following general rules regarding actions can be stated for the functional groups of muscles of the rib cage:

If a muscle attaches to the rib cage and its other attachment is superior to the rib cage attachment, it can elevate the ribs to which it is attached at the sternocostal and costospinal joints.

If a muscle attaches to the rib cage and its other attachment is superior to the rib cage attachment, it can elevate the ribs to which it is attached at the sternocostal and costospinal joints.

If a muscle attaches to the rib cage and its other attachment is inferior to the rib cage attachment, it can depress the ribs to which it is attached at the sternocostal and costospinal joints.

If a muscle attaches to the rib cage and its other attachment is inferior to the rib cage attachment, it can depress the ribs to which it is attached at the sternocostal and costospinal joints.

As a rule, muscles that elevate ribs contract with inspiration and muscles that depress ribs contract with expiration.

As a rule, muscles that elevate ribs contract with inspiration and muscles that depress ribs contract with expiration.

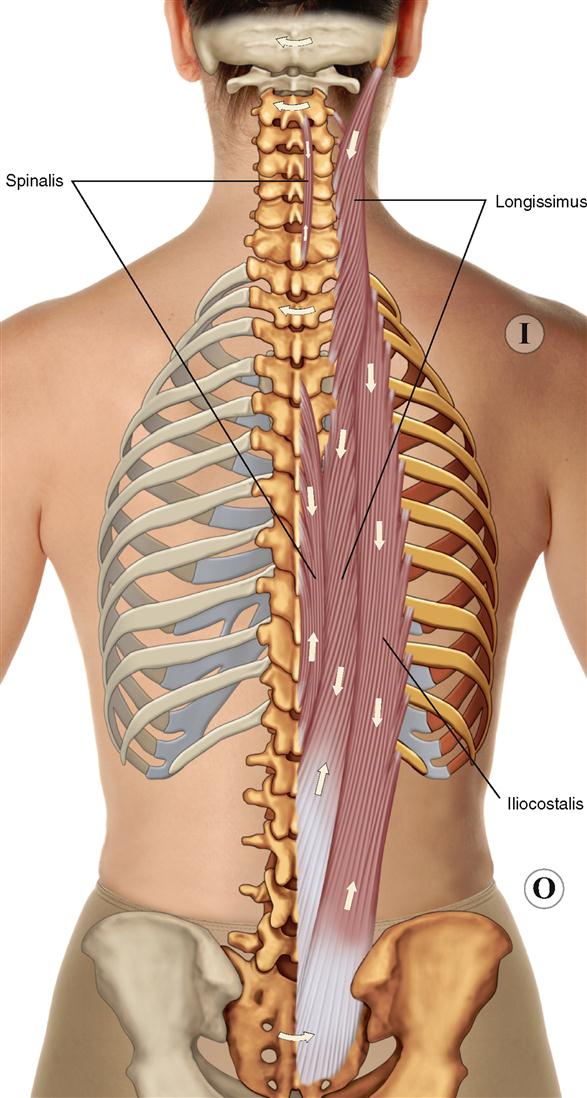

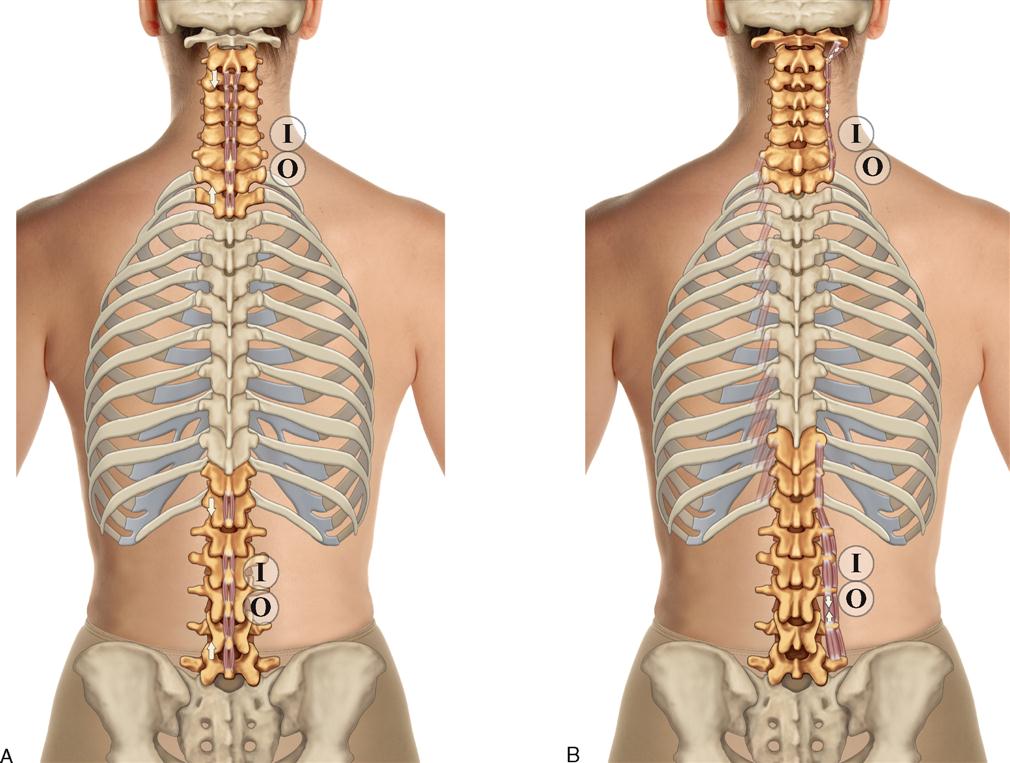

ACTIONS

Extends the trunk, neck, and head at the spinal joints.

Extends the trunk, neck, and head at the spinal joints.

Anteriorly tilts the pelvis at the lumbosacral joint and extends the lower spine relative to the upper spine.

Anteriorly tilts the pelvis at the lumbosacral joint and extends the lower spine relative to the upper spine.

Laterally flexes the trunk, neck, and head at the spinal joints.

Laterally flexes the trunk, neck, and head at the spinal joints.

STABILIZATION

INNERVATION

PALPATION

1. The client is prone. Place your palpating finger pads just lateral to the lumbar spine.

2. Ask the client to extend the trunk; feel for the contraction of the erector spinae musculature in the lumbar region (Figure 8-7). Palpate the erector spinae by strumming perpendicularly; palpate inferiorly to its origin on the pelvis.

3. Now ask the client to extend the trunk, neck, and head; continue palpating it superiorly as far as possible toward its mastoid process attachment.

TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS

Each of the three subgroups of the erector spinae can be further subdivided into three subgroups: (1) iliocostalis lumborum, thoracis, and cervicis; (2) the longissimus thoracis, cervicis, and capitis; and (3) the spinalis thoracis, cervicis, and capitis. Note: The spinalis capitis often blends with and is therefore considered part of the semispinalis capitis of the transversospinalis group.

Each of the three subgroups of the erector spinae can be further subdivided into three subgroups: (1) iliocostalis lumborum, thoracis, and cervicis; (2) the longissimus thoracis, cervicis, and capitis; and (3) the spinalis thoracis, cervicis, and capitis. Note: The spinalis capitis often blends with and is therefore considered part of the semispinalis capitis of the transversospinalis group.

Inferiorly, the erector spinae blends into the thick thoracolumbar fascia.

Inferiorly, the erector spinae blends into the thick thoracolumbar fascia.

The erector spinae is the principal musculature that works when we bend forward. It contracts eccentrically to guide our descent when we bend forward; it contracts isometrically when we hold a bentforward posture; and it contracts concentrically when we stand back up.

The erector spinae is the principal musculature that works when we bend forward. It contracts eccentrically to guide our descent when we bend forward; it contracts isometrically when we hold a bentforward posture; and it contracts concentrically when we stand back up.

Tight erector spinae musculature pulls the pelvis into anterior tilt, which then increases the lordotic curve of the lumbar spine.

Tight erector spinae musculature pulls the pelvis into anterior tilt, which then increases the lordotic curve of the lumbar spine.

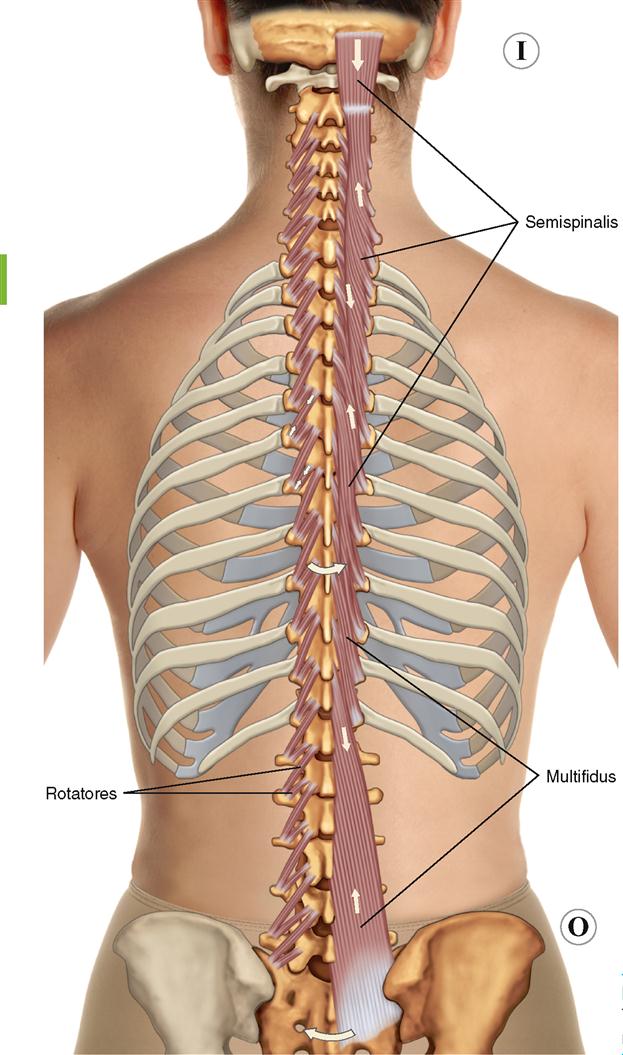

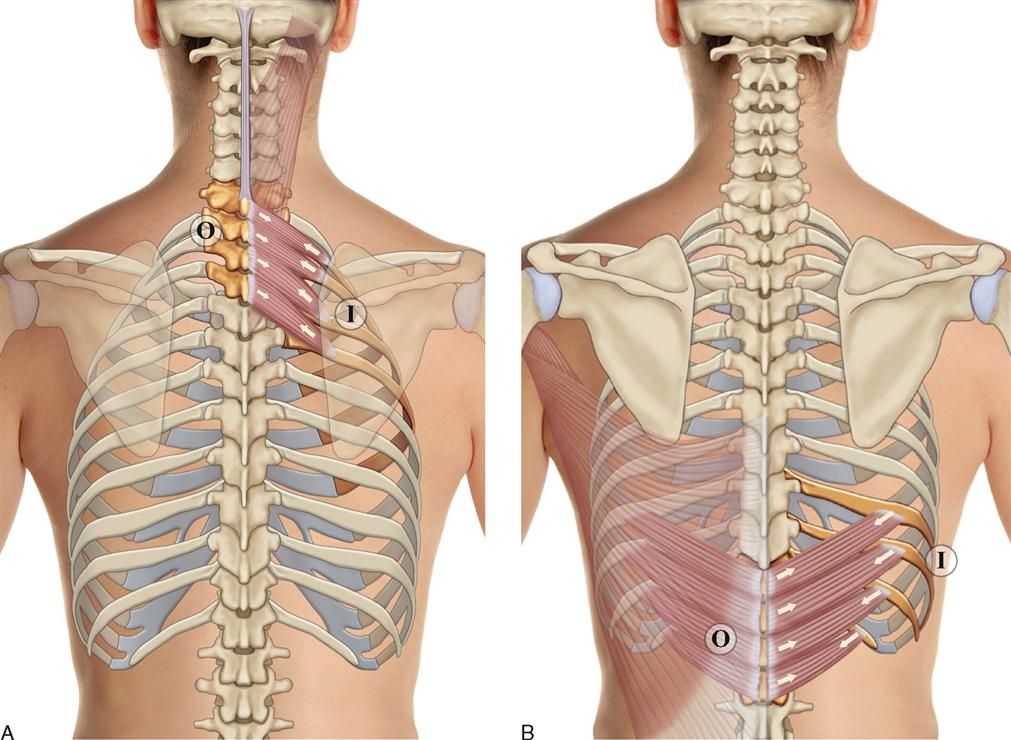

ACTIONS

Extends the trunk, neck, and head at the spinal joints.

Extends the trunk, neck, and head at the spinal joints.

Anteriorly tilts the pelvis at the lumbosacral joint and extends the lower spine relative to the upper spine.

Anteriorly tilts the pelvis at the lumbosacral joint and extends the lower spine relative to the upper spine.

Laterally flexes the trunk, neck, and head at the spinal joints.

Laterally flexes the trunk, neck, and head at the spinal joints.

Contralaterally rotates the trunk and neck at the spinal joints.

Contralaterally rotates the trunk and neck at the spinal joints.

STABILIZATION

INNERVATION

PALPATION

1. The client is prone. Place your palpating finger pads just lateral to the spinous processes of the lumbar spine within the laminar groove.

2. Ask the client to extend and rotate the trunk slightly to the opposite side of the body (contralaterally rotate) at the spinal joints. Feel for the contraction of the transversospinalis musculature of the lumbar spine (Figure 8-9).

3. Repeat this procedure superiorly up the spine.

4. To palpate the semispinalis group in the cervical region, have the client prone with the hand in the small of the back. Place your palpating fingers over the laminar groove of the cervical spine and ask the client to extend the head and neck slightly at the spinal joints. Feeling for the contraction of the semispinalis deep to the upper trapezius (Figure 8-10).

5. Once located, follow the semispinalis up to the attachment on the head by strumming perpendicular to the direction of fibers.

TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS

ACTIONS

Interspinales

Intertransversarii

STABILIZATION

As a group, the interspinales and intertransversarii stabilize the cervical and lumbar spinal joints.

INNERVATION

PALPATION

Interspinales

1. The client is seated. Place your palpating finger pads in the spaces between the spinous processes in the lumbar region. Place your resistance hand on the client’s upper trunk (Figure 8-12).

2. Ask the client to flex slightly forward. Feel for the interspinous muscles between the spinous processes.

3. From this position of flexion, ask the client to extend back to anatomic position, and feel for the contraction of the interspinales muscles. If desired, resistance can be given to the client’s trunk extension with your resistance hand (Figure 8-13).

4. This procedure can be repeated for other interspinales muscles between other spinous processes.

Intertransversarii

TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS

The intertransversarii are considered to be primarily important as stabilizing postural muscles or as proprioceptive organs (not as movers of the spine), thereby providing precise monitoring of spinal joint positions.

The intertransversarii are considered to be primarily important as stabilizing postural muscles or as proprioceptive organs (not as movers of the spine), thereby providing precise monitoring of spinal joint positions.

The interspinales and intertransversarii vary in location. Sometimes they are found at spinal joint levels other than those listed in this textbook; sometimes they are absent at some of their usual locations.

The interspinales and intertransversarii vary in location. Sometimes they are found at spinal joint levels other than those listed in this textbook; sometimes they are absent at some of their usual locations.

Essentially, the intertransversarii do not exist in the thoracic region. The levatores costarum and the intercostals are considered to be homologous with the two sets of intertransversarii in the thoracic region.

Essentially, the intertransversarii do not exist in the thoracic region. The levatores costarum and the intercostals are considered to be homologous with the two sets of intertransversarii in the thoracic region.

ACTIONS

The serratus posterior muscles move ribs at the sternocostal and costospinal joints.

Serratus Posterior Superior

Serratus Posterior Inferior

STABILIZATION

Stabilizes the rib cage.

INNERVATION

PALPATION

The serratus posterior superior and inferior are thin muscles that are located deep to other muscles; therefore they are difficult to palpate and discern. If palpation is done, the client is prone.

Serratus Posterior Superior

Serratus Posterior Inferior

1. Place your palpating finger pads in the upper lumbar region, lateral to the erector spinae.

2. Ask the client to exhale. Feel for the contraction of the serratus posterior superior by strumming perpendicular to its fibers. Discerning the serratus posterior inferior from the overlying latissimus dorsi is very challenging.

TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS

The serrated appearance of the serratus posterior superior and inferior comes from attaching onto separate ribs, which creates the notched look of a serrated knife.

The serrated appearance of the serratus posterior superior and inferior comes from attaching onto separate ribs, which creates the notched look of a serrated knife.

Stabilizing the lower ribs is an important function of the serratus posterior inferior. Its force of depression of the lower ribs stabilizes them from elevating when the diaphragm contracts and pulls superiorly on them.

Stabilizing the lower ribs is an important function of the serratus posterior inferior. Its force of depression of the lower ribs stabilizes them from elevating when the diaphragm contracts and pulls superiorly on them.

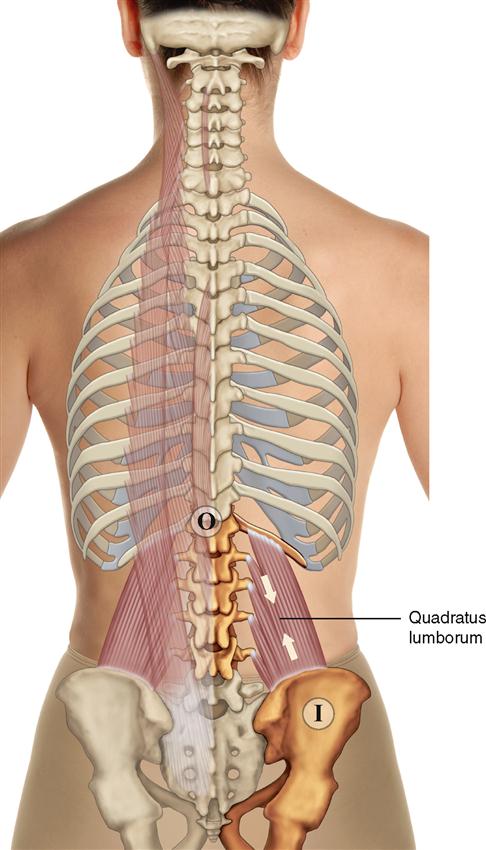

ATTACHMENTS

Origin (Proximal Attachment)

Insertion (Distal Attachment)

ACTIONS

The quadratus lumborum moves the trunk at the spinal joints, the pelvis at the lumbosacral joint, and the twelfth rib at the costospinal joint.

Elevates the same-side pelvis.

Elevates the same-side pelvis.

Anteriorly tilts the pelvis and extends the lower lumbar spine relative to the upper lumbar spine.

Anteriorly tilts the pelvis and extends the lower lumbar spine relative to the upper lumbar spine.

STABILIZATION

Stabilizes the pelvis, lumbar spinal joints, and twelfth rib.

INNERVATION

PALPATION

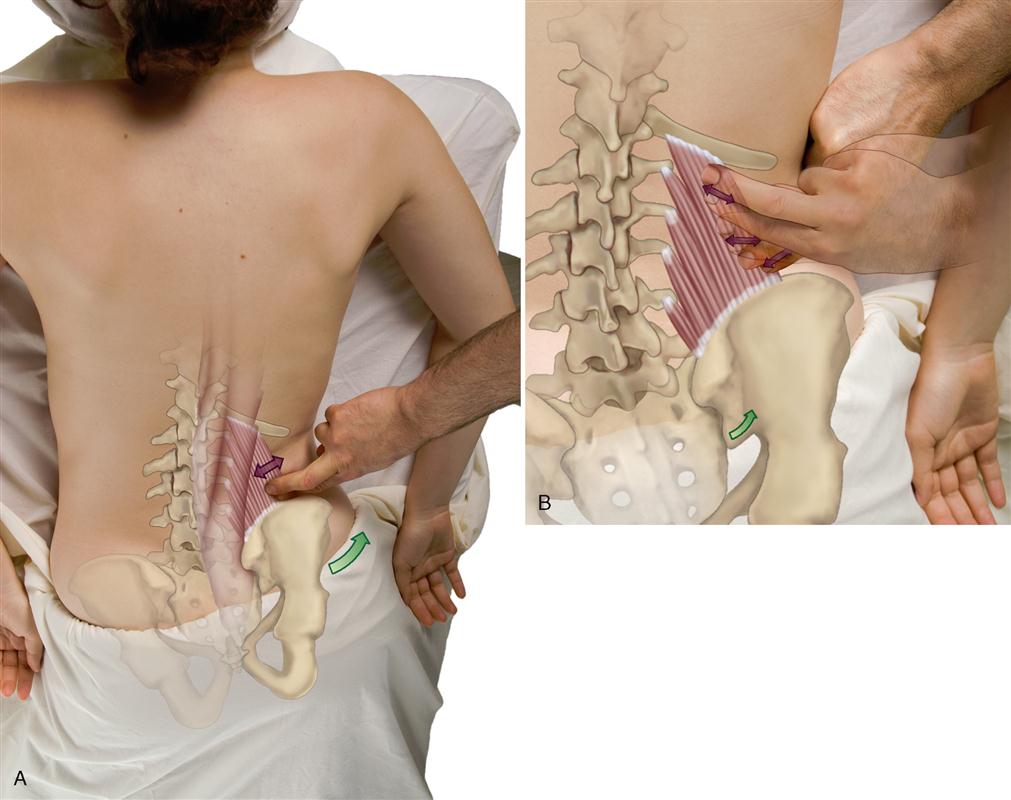

1. The client is prone. Place your palpating finger pads just lateral to the lateral border of the erector spinae in the lumbar region.

2. First locate the lateral border of the erector spinae musculature. (To do so, ask the client to raise the head and upper trunk from the table.) Then place your palpating finger just lateral to the lateral border of the erector spinae.

3. Direct palpating pressure medially, deep to the erector spinae musculature, and feel for the quadratus lumborum.

4. To engage the quadratus lumborum, ask the client to elevate the pelvis on that side at the lumbosacral joint and feel for its contraction (Figure 8-16, A).

5. Once located, palpate medially and superiorly toward the twelfth rib, medially and inferiorly toward the iliac crest, and directly medially toward the transverse processes of the lumbar spine (Figure 8-16, B).

TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS

When working on the quadratus lumborum, you can position the client either prone, supine, or side lying. However, because much of this muscle is deep to the massive erector spinae musculature, it must be accessed with palpatory pressure from lateral to medial (i.e., come in from the side).

When working on the quadratus lumborum, you can position the client either prone, supine, or side lying. However, because much of this muscle is deep to the massive erector spinae musculature, it must be accessed with palpatory pressure from lateral to medial (i.e., come in from the side).

Keep in mind that the quadratus lumborum is not the only muscle in the lateral lumbar region and should not be blamed for all the pain in this area. The nearby erector spinae musculature is also likely to develop tension and pain.

Keep in mind that the quadratus lumborum is not the only muscle in the lateral lumbar region and should not be blamed for all the pain in this area. The nearby erector spinae musculature is also likely to develop tension and pain.

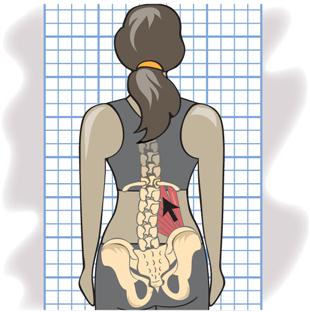

If the quadratus lumborum is tight, it can pull up on the pelvic bone, causing the iliac crest on that side to elevate. This elevation can be seen during the postural assessment examination.

If the quadratus lumborum is tight, it can pull up on the pelvic bone, causing the iliac crest on that side to elevate. This elevation can be seen during the postural assessment examination.

The quadratus lumborum is important for stabilizing the twelfth rib when the diaphragm contracts during inspiration. Stabilization increases the efficiency of the diaphragm during breathing.

The quadratus lumborum is important for stabilizing the twelfth rib when the diaphragm contracts during inspiration. Stabilization increases the efficiency of the diaphragm during breathing.

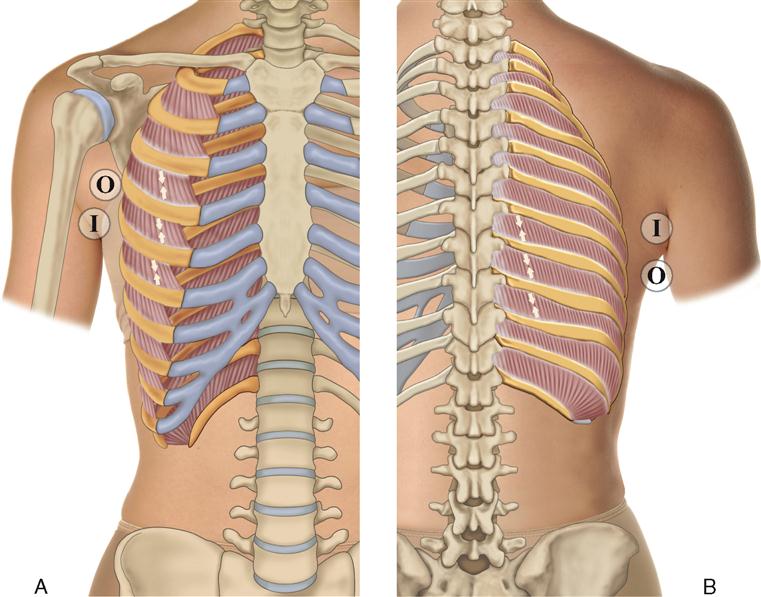

ACTIONS

The intercostals move the ribs at the sternocostal and costospinal joints and move the trunk at the spinal joints.

The intercostals move the ribs at the sternocostal and costospinal joints and move the trunk at the spinal joints.

External Intercostals

Internal Intercostals

STABILIZATION

Stabilize the rib cage.

INNERVATION

PALPATION

1. The client is side lying. Place your palpating finger pads in the intercostal spaces (between ribs) in the lateral trunk (Figure 8-18).

2. To locate an intercostal space, feel for the hard texture of the ribs in the lateral trunk and then drop your palpating fingers into the soft intercostal space between them.

3. Once located, palpate in the intercostal space as far posteriorly and anteriorly as possible. The presence of breast tissue in female clients makes it difficult to access fully the intercostals anteriorly.

TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS

Controversy exists over the exact actions of the intercostals. However, it is clear that they are involved in respiration. Therefore the intercostals should be addressed in any client who has a respiratory condition, especially a chronic one such as asthma, emphysema, or bronchitis, or simply a chronic cough.

Controversy exists over the exact actions of the intercostals. However, it is clear that they are involved in respiration. Therefore the intercostals should be addressed in any client who has a respiratory condition, especially a chronic one such as asthma, emphysema, or bronchitis, or simply a chronic cough.

Athletes may also greatly benefit from having these muscles worked on because of the great demand for respiration during exercise.

Athletes may also greatly benefit from having these muscles worked on because of the great demand for respiration during exercise.

The intercostals are also involved in fixation (i.e., stabilization) of the rib cage during other movements of the body.

The intercostals are also involved in fixation (i.e., stabilization) of the rib cage during other movements of the body.

Anteriorly the internal intercostals are located in the spaces between the costal cartilages; the external intercostals are not.

Anteriorly the internal intercostals are located in the spaces between the costal cartilages; the external intercostals are not.

The intercostal muscles are the meat that is eaten when one eats ribs or spare ribs.

The intercostal muscles are the meat that is eaten when one eats ribs or spare ribs.