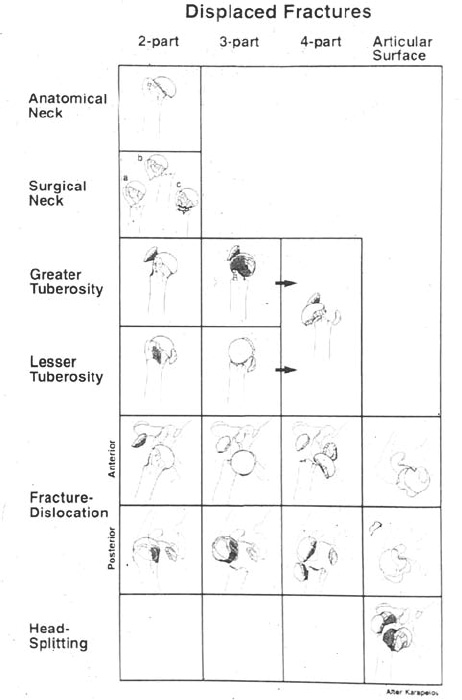

Case 3 A 71-year-old healthy, active, right-hand-dominant woman presents to the office several hours after falling onto her right shoulder. She complains of pain and crepitus with range of motion. She denies any other injury. Range of motion of the shoulder is limited secondary to pain. There is crepitus with any attempted motion. Moderate swelling about the shoulder is seen. The patient is neurovascularly intact both in the area of the shoulder and more distally. Figure 3–1. An anteroposterior (AP) (A) and scapular Y (B) view of the affected shoulder. 1. Proximal humerus fracture 2. Shoulder dislocation 3. Rotator cuff tear An anteroposterior (AP) and scapular Y view of the shoulder are obtained (Fig. 3–1). Displaced, Three-Part Fracture. Pain, swelling, and crepitus to range of motion are suggestive of a proximal humerus fracture. Radiographs confirm the diagnosis. Treatment options include immobilization in an arm sling followed by progressive range of motion, an attempt at closed reduction, and open reduction and internal fixation. The choice of treatment depends on the degree of displacement of the fracture fragments and the activity level and health of the patient. Neer’s (1970a) classification system has proved very helpful in the management of proximal humerus fractures (Fig. 3–2). Eighty-five percent of proximal humerus fractures are considered one-part or nondisplaced and are effectively treated with early functional exercises. The remaining 15% represent Neer’s displaced fractures. Accurate diagnosis of the number of fracture fragments, as well as their displacement and angulation relative to one another, are important in determining the best treatment. Three radiographic views are required for any shoulder injury, to ensure consistent identification of the fracture type. Also computed tomography (CT) scanning can often be valuable in assessing fracture fragment position and orientation. The rationale for treatment of displaced three-part proximal humerus fractures is based on the proper classification of the fracture type, appreciation of the patient’s activity level, and the experience of the treating surgeon. A discussion with the patient about realistic goals must be entertained prior to the initiation of any treatment plan. Also, the patient’s general activity level and ability to cooperate with a prolonged rehabilitation program must be determined. In some cases, acceptance of the deformity may be preferable to an attempt at open reduction and internal fixation. However, nonoperative treatment should be reserved for very sedentary patients, patients with severe medical problems, and patients with limited expectations. Figure 3–2. The Neer classification system for proximal humerus fractures. PEARLS • Even when a plate and screw construct is used to reapproxi-mate a three-part fracture, supplemental suture passage through the tendons and under the plate will effectively supplement fracture fragment stability. • Partial release of the pectoralis major muscle insertion often decreases the tendency of the distal fragment to medialize postoperatively after suture fixation of the fracture fragments. Also, avoiding the use of abduction pillows will likewise minimize this tendency. • Careful radiographic follow-up postoperatively will help ensure that significant displacement does not occur. PITFALLS • Failure to recognize the significant displacement that occurs in three-part fractures may severely compromise the patient’s postinjury function. CT scanning is recommended for any patient whose displacement is not easily recognizable with routine three-view shoulder radiographs. • Patients with three-part fractures usually have significant osteopenia, making fracture fragment fixation difficult and/or tenuous. Suture passage through the rotator cuff tendons provides superior stability over the tuberosity fragments in most cases. • When a plate and screw construct is employed, care must be taken to avoid superior plate placement, as the plate will impinge within the subacromial space.

History and Physical Examination

Differential Diagnosis

Radiologic Findings

Diagnosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree