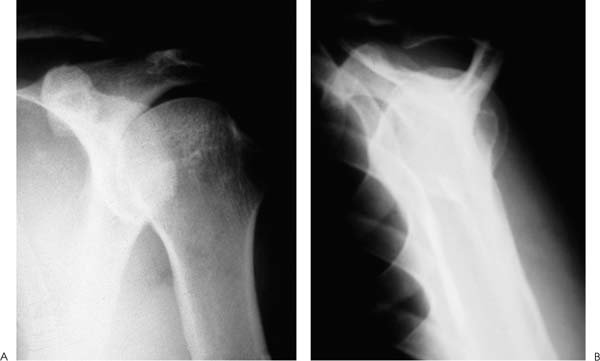

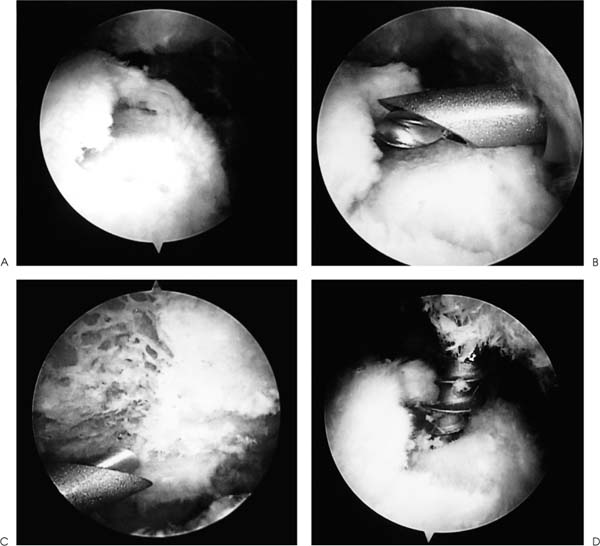

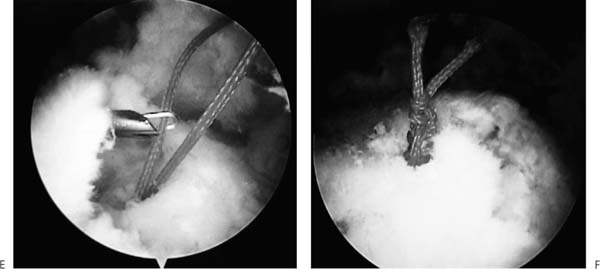

Case 22 A 61-year-old recreational tennis player presents with a 14-month history of intermittent shoulder pain. He states that it is worse when participating in overhead-motion sports, but often limits his ability to do any overhead-motion activity. He also complains of night pain and difficulty sleeping. He denies any numbness or significant weakness in the shoulder. His primary care physician has overseen 5 months of organized rotator cuff strengthening exercises and has given him two subacromial steroid injections, which helped temporarily in the months prior to presentation. The patient demonstrates active forward flexion of 150 degrees and passive of 170 degrees. He has a moderately positive impingement sign and a positive Hawkins impingement sign. He has no tenderness about the shoulder to palpation and has normal passive range of motion otherwise. His external rotation strength is normal, but his forward flexion strength is 3/5. He is neurovascularly intact on examination and demonstrates no neck pathology on examination or by history. Figure 22–1. An anteroposterior (AP) (A) and scapular Y (B) view radiograph of this patient. 1. Chronic impingement syndrome 2. Glenohumeral arthritis 3. Full-thickness rotator cuff tear 4. Anterior shoulder instability An anteroposterior (AP) and scapular Y view of the shoulder are obtained (Fig. 22–1). Full-Thickness Rotator Cuff Tear. This patient’s history of persistent symptoms despite a rather extensive nonoperative treatment program including organized physical therapy and subacromial injections suggest chronic impingement or full-thickness rotator cuff tearing. His significant weakness to forward flexion makes the possibility of a full-thickness rotator cuff tear more likely. His normal passive motion and the absence of significant degenerative changes radiographically make significant arthritis a much less likely etiology. Although this patient may not actually have a full-thickness rotator cuff tear, his moderately persistent symptoms despite these nonoperative interventions make surgical treatment a valuable alternative. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) would probably assess the status of the rotator cuff accurately. However, the authors would generally not obtain an MRI in this situation because, regardless of whether a tear exists, this patient would certainly benefit from an acromioplasty. Because the authors perform this decompression arthroscopically, an excellent opportunity for accurate assessment of the rotator cuff tendon both on the articular and bursal sides would be possible. The authors have found MRI to be more valuable for patients with significant functional deficits who have failed to respond to an organized program for several weeks. This is particularly true in younger or athletically inclined individuals who sustain an acute, traumatic injury. Although rotator cuff contusions can lead to significant losses of active motion for a few weeks, persistent loss of active function is usually due to a complete tear, and MRI is valuable in assessing the status of the tendon. Patients failing to respond to an adequate nonoperative treatment program including organized exercises and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medications are candidates for surgical intervention. Repair of full-thickness rotator cuff tears by open subacromial decompression and rotator cuff tendon reapproximation has proven successful in restoring function and decreasing pain in patients who have failed nonoperative treatment. However, open rotator cuff repair does have certain inherent limitations and drawbacks. Failure of the deltoid repair following open rotator cuff surgery has been reported and may lead to significant functional deficits in postoperative strength and in active motion. Also, active strengthening exercises must always be delayed following deltoid muscle release in an effort to protect the deltoid repair. Detachment of the deltoid can be avoided through the use of an arthroscopically assisted deltoid splitting mini-arthrotomy technique or a purely arthroscopic technique. However, these mini-open or purely arthroscopic approaches to rotator cuff repair can be used only after an arthroscopic subacromial decompression has been performed. Acromioplasty cannot be effectively accomplished through a mini-open incision. Arthroscopically assisted rotator cuff repair can be accomplished with the patient in either the lateral decubitus or beach chair position. Regardless of patient position, the procedure begins with a complete and thorough examination of the glenohumeral joint. Standard anterior and posterior portals are established and glenohumeral visualization is accomplished. A significant percentage of patients with rotator cuff tears exhibit additional pathology intraarticularly. This may include partial biceps tendon tears, superior labrum anterior and posterior (SLAP) lesions, labral tears, and articular cartilage injuries. Also, a significant reactive synovitis often develops intraarticularly, and arthroscopic debridement can be valuable. Following the assessment and treatment of any intraarticular pathology that is identified, careful evaluation of the undersurface of the rotator cuff is carried out. When a partial-thickness articular surface tear or full-thickness rotator cuff tear is present, significant fraying and tendinous scarring is seen. Debridement of the rotator cuff undersurface allows for more accurate assessment of the thickness and dimensions of the tear. However, differentiating a large partial-thickness articular surface rotator cuff tear from a full-thickness tear is often difficult. For this reason, the authors commonly employ a marking suture that allows for localization of the corresponding bursal surface of the rotator cuff tendon when the arthroscope is transferred to the subacromial space. This marking suture is placed into the area of question by using a spinal needle placed through the rotator cuff tendon in this area. A colored polydioxynone suture (PDS) is then passed through the spinal needle and retrieved out the anterior portal cannula. The two ends of the suture are tagged using a hemostat and attention is turned to the subacromial space. A lateral portal is then established and a complete bursectomy accomplished arthroscopically. The PDS marking suture is then identified and the area of the tendon through which it passes carefully evaluated. A full-thickness rotator cuff tear is generally easily seen, but occasionally probing in the area of the suture is required to confirm the full-thickness nature of the tearing. When no full-thickness tearing is present, this PDS marking suture provides an excellent method for localization of the partial-thickness articular surface tear. When a full-thickness rotator cuff tear is identified, debridement of the rotator cuff edges is accomplished arthroscopically (Fig. 22–2). The underlying greater tuberosity bone is then abraded using the arthroscopic instruments. Care is taken not to disrupt the cortical surface of the greater tuberosity as this may significantly reduce the pull-out strength of the suture anchors to be employed. Attention is then turned to the acromion, where an arthroscopic acromioplasty is carried out using standard technique. Following the completion of an arthroscopic decompression, the rotator cuff tendon is evaluated for its ability to be lateralized into the bleeding bony bed. If mobilization of the tendon is required, this can often be accomplished arthroscopically. Small freers can allow for significant lateralization of small, medium, and even some large tears. When adequate mobilization has been accomplished, suture anchors can be placed into the bleeding bony bed in the area of the anatomic insertion of the tendon. The authors prefer no. 2 nonabsorbable sutures for rotator cuff repair, and such sutures are threaded through the eyelet of the anchor prior to placement. The number of suture anchors varies depending on the size and character of the rotator cuff tendon tear. As a general rule, the authors use one anchor for every centimeter of detached rotator cuff tendinous tissue. As each suture anchor is placed into the bleeding bony bed under arthroscopic visualization, a suture retriever is then passed through the substance of the tendon using an accessory portal and the ends retrieved through the tendon and out the accessory portal. The authors have found it easiest to complete the passage and tying of an individual suture anchor before proceeding to the placement and passing of the sutures for a second anchor. Such a technique allows for a minimum number of intraarticular sutures, making orientation easier and suture overlapping less likely. However, all sutures may be passed before any are tied depending on the size and orientation of the rotator cuff tear. Following the completion of suture anchor placement, suture passage through the tendon, and arthroscopic knot tying, a probe is used to confirm the adequacy and stability of the repair. Figure 22–2. Arthroscopic identification and treatment of a full-thickness rotator cuff tear. (A) The full-thickness rotator cuff tear is identified by visualizing the rotator cuff from the posterior portal while in the subacromial space. (B) Debridement of the rotator cuff edges and abrasion on the underlying greater tuberosity bone are then carried out. (C) An arthroscopic acromioplasty as viewed from the lateral portal is carried out using standard technique. (D) While viewing from the posterior portal, suture anchors are placed into the bleeding bony bed of the greater tuberosity arthroscopically. (See Color Plates 22–2A–D.) Figure 22–2 (continued). (E) The nonabsorbable sutures are passed through the rotator cuff tendon using a suture retriever. (F) Arthroscopic knot tying then allows for reapproximation of the tendinous tissue into the previously abraded greater tuberosity bony bed (See Color Plates 22–2E,F.) When a purely arthroscopic technique for rotator cuff repair is not possible or technical factors preclude its implementation, a mini-open rotator cuff repair technique is used. The authors have found that the great majority of rotator cuff tears can be repaired through this mini-open approach, making deltoid detachment rarely necessary. The mini-open repair technique is exactly the same as the purely arthroscopic technique until the placement of suture anchors is to be carried out. That is, arthroscopic glenohumeral joint evaluation, arthroscopic rotator cuff debridement, and greater tuberosity abrasion along with arthroscopic acromioplasty are accomplished prior to carrying out the limited arthrotomy. Following the completion of the arthroscopic component of the procedure, a limited transverse incision is made over the shoulder in the area where the rotator cuff tendon tear is present. This transverse incision has been found by the authors to be much more cosmetically pleasing than a longitudinal incision of the same length (Fig. 22–3). After incision of the skin has been completed, the deltoid is bluntly split in line with its fibers and the subacromial space entered. A self-retaining retractor is placed in the deltoid split. No deltoid is released from the acromion, but care is taken to avoid avulsion of the deltoid from the acromion. This is particularly true after arthroscopic resection of a large amount of subacro mial bone. Extensive removal of bone can weaken the insertion of the deltoid, making intraoperative avulsion a possibility. The rotator cuff tendon tear can then be identified within the depths of the incision. The size of the rotator cuff tear and quality of the tissue can be assessed. Traction sutures or small graspers can be used to assess the mobility of the rotator cuff tissue. Suture anchors are then placed into the previously abraded greater tuberosity bed if the bone is of adequate quality. If significant osteopenia is present and precludes the use of suture anchors, a no. 2 or no. 5 nonabsorbable suture can be passed through transosseous drill holes and tied over the greater tuberosity. Also, a Marlex patch is sometimes used by the authors over the greater tuberosity to further reinforce the bony post where the sutures are tied. This is accomplished by simply passing the sutures through the Marlex patch prior to tying, so that these sutures are tied not only over the greater tuberosity bone but over this patch as well. When suture anchors are used, they are placed into the bleeding bony bed using standard technique, with the drill holes directed toward the glenohumeral joint. The sutures are then passed in a horizontal mattress fashion and sequentially tied. The rotator cuff repair is then assessed for stability by probing and under direct visualization through a range of motion. Following the confirmation of the adequacy of repair, the deltoid fascia is reapproximated with interrupted absorbable sutures. The sub-cutaneous tissues are reapproximated with absorbable sutures and a running subcuticular 4-0 PDS is used to approximate the skin. PEARLS • The arthroscope serves as an extremely valuable tool in the assessment and treatment of rotator cuff pathology, and the authors recommend its routine use. • Use of a PDS marker can allow for localization of a nearly complete partial-thickness articular surface rotator cuff tear when viewed from the subacromial space. Likewise, a small complete tear may be difficult to identify without the use of this suture marker. • A limited transverse incision centered over the area of the underlying rotator cuff tear produces a pleasing cosmetic scar and allows for excellent access to the tendon tear. • Performing the greater tuberosity abrasion with the arthroscopic instruments allows for a more controlled abrasion and makes the use of an air-powered burr unnecessary at the time of arthrotomy. This is important because the limited incision makes placement of such an instrument and visualization more difficult.

History and Physical Examination

Differential Diagnosis

Radiologic Findings

Diagnosis

Surgical Management

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree