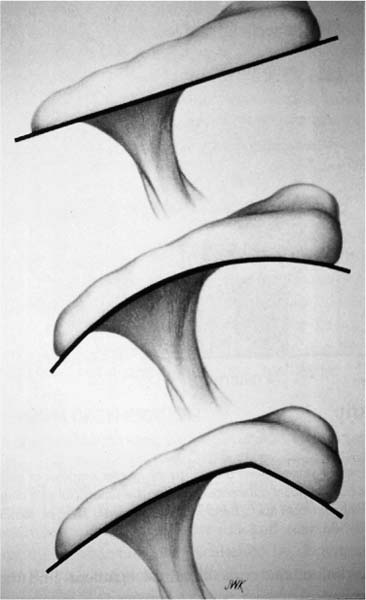

Case 20 A 51-year-old, active, recreational tennis player presents with a history of intermittent shoulder pain over the last several years. He reports increased symptoms associated with tennis. He has had two or three injections in the shoulder over the last several years. He denies any numbness or weakness in the ipsilateral extremity. He also denies any neck symptoms. Finally, he reports difficulty sleeping on the affected side due to shoulder pain. Evaluation of range of motion demonstrates no abnormality except for a four vertebral level loss of internal rotation. He has normal strength and normal stability. There is no atrophy or asymmetry and he is neurovascularly intact. Evaluation of the neck is benign. He has a positive impingement sign, but no other abnormalities are identified. Figure 20–1. A scapular Y view radiograph demonstrating a marked acromial curve. 1. Full-thickness rotator cuff tear 2. Impingement syndrome 3. Osteoarthritis of the glenohumeral joint 4. Partial thickness rotator cuff tear A scapular Y view is presented (Fig. 20–1). Impingement Syndrome with Subacromial Decompression. This patient’s classic history of exercise-associated shoulder pain in the presence of a positive impingement sign, along with well-maintained shoulder strength, helps to confirm the diagnosis of impingement syndrome. While partial-thickness rotator cuff tears could certainly exist in this clinical situation, a large full-thickness rotator cuff tear is unlikely because of the near-normal range of motion and normal strength. The patient is still functioning at a high level in the presence of these symptoms. Impingement syndrome is one of the most common causes of shoulder pain and dysfunction. Neer (1983) proposed three stages in the development of impingement syndrome: stage I, a reversible stage in which edema and hemorrhage predominate; stage II, an irreversible stage in which tendinitis and fibrosis have occurred; and stage III characterized by significant tendon degeneration and tearing. Stage I and most stage II lesions respond to a conservative program consisting of exercises, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, and, occasionally, corticosteroid subacromial injections. Structural factors that contribute to rotator cuff impingement include acromial shape. Three types of acromial shape have been described: type I, which demonstrates a flat acromial undersurface; type II, which is curved and seen in the majority of patients; and type III, which demonstrates a hooked acromion (Fig. 20–2). Hooked acromions are seen much more commonly in patients with irreversible rotator cuff tendinitis or rotator cuff tears. Other causes of decreased space within the supraspinatus outlet include acromioclavicular joint osteophytes, hypertrophy of the coracoacromial ligament, malunion of greater tuberosity fractures, inflammatory bursitis, calcific tendinitis, and a flap of rotator cuff tendon secondary to a bursal-sided partial-thickness tear. Some of these contributing factors can be identified radiographically, but many are identified only at the time of surgery. Figure 20–2. Acromial morphology varies and has been shown to correlate with rotator cuff tearing. Impingement syndrome remains a clinical diagnosis, despite significant advances in imaging. While magnetic resonance imaging has been shown to have the capability of identifying full-thickness rotator cuff tears with a high degree of sensitivity and specificity, this imaging technique is not often useful in the absence of significant rotator cuff tearing. Patients with impingement syndrome usually present with an insidious onset of shoulder pain. Range of motion is generally maintained in these patients, although some loss of internal rotation is common. Strength is often near normal as well, although significant pain may limit the clinical assessment. Inspection may reveal atrophy, but often does not. Likewise, while tenderness may be exhibited in the area of the subacromial bursa or the anterior acromion, palpable tenderness is usually not found unless significant acromioclavicular joint degeneration is present. The impingement sign originally described by Neer to aid in the diagnosis of impingement has proven very valuable. This sign is elicited when the patient’s arm is elevated in forward flexion and the humerus internally rotated, while stabilizing the scapula. This motion compresses the rotator cuff against the undersurface of the acromion, causing pain. Hawkins’ sign is a variation of this provocative maneuver and is accomplished by forward flexing the shoulder to 90 degrees and then forcibly internally rotating the glenohumeral joint. This maneuver drives the greater tuberosity under the coracoacromial ligament, thereby producing impingement pain. The impingement test originally described by Neer is performed by injecting 10 cc of Xylocaine into the subacromial space. If shoulder pain and impingement signs are reduced by the injection, a diagnosis of impingement syndrome can be made with confidence. The majority of patients with impingement syndrome can be successfully treated with an organized rehabilitation program. An important component of this treatment program involves avoiding activities that predispose to injury. An organized exercise program, under the supervision of an athletic trainer or physical therapist, will often allow for the restoration of pain-free motion and the recovery of rotator cuff strength. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medications and occasionally subacromial space corticosteroid injections can be of benefit as well. Persistent impingement symptoms unresponsive to 3 to 6 months of organized rehabilitation can be effectively treated with acromioplasty. The authors perform arthroscopic acromioplasty, except in very rare instances. The advantages of arthroscopic acromioplasty include better cosmesis, less postoperative morbidity, the ability to perform a complete intraarticular examination, and an early, accelerated rehabilitation program. Arthroscopic subacromial decompression can be accomplished with the patient in either the beach chair or lateral decubitus position. In the beach chair position, a total-body suction-fitted beanbag or special beach chair positioner is used for patient support. The trunk is oriented 70 to 80 degrees to the plane of the floor. The scapula is positioned laterally over the edge of the table to allow for complete access to the shoulder. The shoulder is carefully examined under anesthesia, allowing an accurate assessment of motion and stability. Anterior translation, posterior translation, and an assessment of inferior stability are all accomplished under anesthesia. Comparison with the contralateral shoulder is very important in accurately determining whether or not shoulder instability exists. Following the completion of a sterile preparation and draping of the shoulder, standard posterior and anterosuperior portals are established. A thorough examination of the glenohumeral joint is undertaken with careful inspection of the labrum and articular surfaces of the glenoid and humeral head. Following evaluation of the joint, attention is turned to the articular surface of the rotator cuff tendon. When the beach chair position is employed, the arm is placed in approximately 45 degrees forward flexion, 30 degrees of abduction, and 10 degrees of external rotation. This allows for complete rotator cuff visualization. The cuff undersurface is then carefully inspected. Arthroscopic acromioplasty is accomplished after a complete subacromial space evaluation. While visualizing through the previously placed posterior portal, with flow through the anterior portal, a lateral portal is established approximately 2 cm inferior to the lateral edge of the acromion. A complete bursectomy is accomplished with the arthroscopic instruments. This allows for an inspection of the bursal surface of the rotator cuff. Inadequate bursectomy may significantly compromise the surgical result secondary to poor visualization. The coracoacromial ligament should be clearly visible at the roof of the subacromial space. Following bursectomy and subacromial evaluation, an arthroscopic acromioplasty can be performed. Although electrocautery is sometimes useful in peeling the coracoacomial ligament from the undersurface of the acromion, the authors rarely find it necessary. The anterior acromioplasty is performed using a notchplasty blade. While visualizing through the posterior portal, the arthroscopic burr is used in the lateral portal and release of the coracoacromial ligament is accomplished. The remaining soft tissues attached to the undersurface of the acromion are then removed. The portal sites are then transferred, and by visualizing through the lateral portal, an acromioplasty is accomplished by working through the posterior portal. Resection of the acromion through the posterior portal is preferred by the authors, as the posterior aspect of the acromion provides an excellent “cutting block” that helps ensure adequate but not excessive anterior acromial resection (Fig. 20–3). Following resection of the acromion through the posterior portal, the arthroscope is placed in the posterior portal to confirm adequate bony resection, particularly along the lateral edge of the acromion. After an adequate resection is confirmed, any acromioclavicular osteophytes can be removed as well. The distal clavicle may then be excised arthroscopically if necessary. PEARlS • Performing the acromial resection through the posterior portal allows for a very reproducible method of bone resection. • Following completion of the acromioplasty, the arthroscope should be inserted into the posterior portal to ensure that an adequate lateral resection has been performed. • For surgeons learning the technique of arthroscopic acromioplasty, simply extending the lateral portal will allow for the insertion of a finger for digital palpation of the undersurface of the acromion, confirming adequate bone removal.

History and Physical Examination

Differential Diagnosis

Radiologic Findings

Diagnosis

Surgical Management

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree